Part Two: The Stereo Revolution Continues Conclusion of Our Two-Part Series on the History of FM Radio Wait!! Missed Part One? Go here. W

Part Two: The Stereo Revolution Continues

Conclusion of Our Two-Part Series on the History of FM Radio

Wait!! Missed Part One? Go here.

Welcome back to the second and final installment of our deep dive into the world of FM radio. In Part One, we traced the roots of frequency modulation from Edwin Armstrong’s spark of genius to the quiet persistence that carried FM through its earliest decades.

Now, in Part Two, we pick up the signal right as FM begins to rise—transforming from a niche format into a cultural powerhouse that redefined music, youth identity, and radio itself. From the rule-breaking DJs of the ’60s to the format revolutions of the ’70s and beyond, this is the story of how FM didn’t just find its voice… it found ours.

Let’s turn this dial one last time . . . .

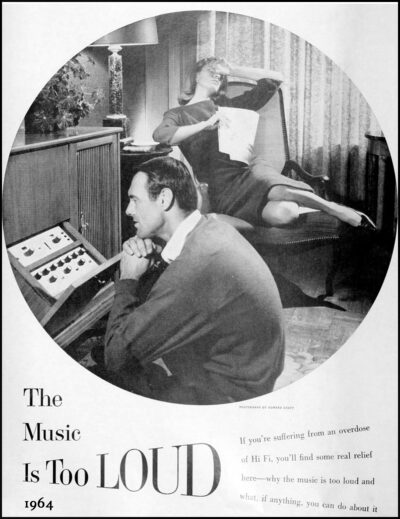

1964: 25 Years of Fidelity

By mid-1964, FM radio had traveled a long, winding path from invention to ascendance. What began in 1939 as a quiet experimental transmission atop the Palisades of Alpine, New Jersey, had become a burgeoning medium with the potential to reshape how Americans consumed sound. That July, the industry paused to honor its origins with an anniversary broadcast that did more than just commemorate the past—it signaled that FM’s future had finally arrived.

By mid-1964, FM radio had traveled a long, winding path from invention to ascendance. What began in 1939 as a quiet experimental transmission atop the Palisades of Alpine, New Jersey, had become a burgeoning medium with the potential to reshape how Americans consumed sound. That July, the industry paused to honor its origins with an anniversary broadcast that did more than just commemorate the past—it signaled that FM’s future had finally arrived.

On July 18, 1964, listeners tuning in to WQXR-FM in New York were treated to a faithful recreation of the very first FM broadcast, originally transmitted by Edwin Howard Armstrong twenty-five years earlier. The program, which included Haydn’s Symphony No. 100 and Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini, served as both tribute and testament. FM had survived regulatory upheaval, wartime stagnation, and corporate resistance. It had weathered its inventor’s tragic end. Now, it stood on the threshold of widespread adoption, with a growing audience and a reputation for crystal-clear sound that AM could no longer match.

This wasn’t merely a symbolic milestone—it was part of a larger, tangible momentum sweeping the FM band. Throughout 1964, FM stations were beginning to broaden their sonic identities. While classical programming still dominated much of the schedule, more and more broadcasters were experimenting with a variety of formats, weaving in jazz, folk, spoken word, and even contemporary rock. These weren’t just musical curiosities—they were strategic choices. FM was learning to speak in many voices, to cater to new and younger audiences eager for programming that felt less commercial, less repetitive, and more immersive.

At the same time, regulators were starting to take serious notice. That year, the Federal Communications Commission floated proposals to limit AM/FM content duplication, particularly in larger cities where FM’s potential remained underutilized. While still a suggestion, it carried weight. The implication was clear: FM was not to be a mere shadow of its AM sibling. It needed to cultivate its own programming and earn its own audiences. The pressure to differentiate would only intensify in the years to come, but in 1964, the seeds were already being planted.

It was a year of both celebration and subtle transformation. FM was no longer simply a medium of technical elegance—it was beginning to find its editorial voice, its cultural rhythm, and its distinct identity. If 1939 had been the signal’s spark, 1964 marked its ignition. And with more stations flipping the switch and more listeners turning the dial, FM was preparing to speak not just in stereo—but in full chorus.

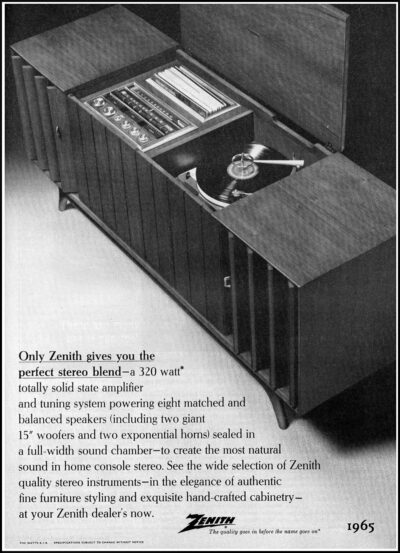

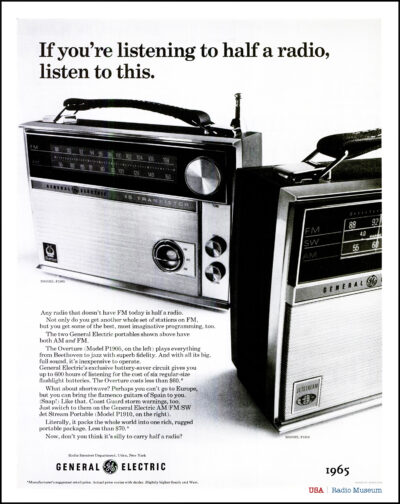

1965: From Sales to Cultural Force

As 1965 unfolded, FM radio could no longer be dismissed as a fringe technology or a niche indulgence for hi-fi enthusiasts. It was now a full-fledged commercial phenomenon—and increasingly, a cultural one. That year marked the moment when FM moved from the periphery of American broadcasting into the living rooms, dashboards, and imaginations of mainstream consumers.

As 1965 unfolded, FM radio could no longer be dismissed as a fringe technology or a niche indulgence for hi-fi enthusiasts. It was now a full-fledged commercial phenomenon—and increasingly, a cultural one. That year marked the moment when FM moved from the periphery of American broadcasting into the living rooms, dashboards, and imaginations of mainstream consumers.

Dealers across the country were beginning to speak in a new vernacular, shaped by a surge in customer demand that no longer saw FM as a luxury. As one retailer confessed to Billboard in October 1965, “Even in the moderate-cost table lines our customers want AM/FM.” No longer the preserve of the high-end stereo cabinet or the tinkerer’s tuner, FM receivers were now flying off store shelves at a historic clip.

The numbers told the story with clarity: sales of FM-equipped radios had tripled since 1960. An estimated 7.5 million FM units were expected to sell that year alone, encompassing everything from tabletop clock radios and portable units to sophisticated hi-fi consoles and component systems. One of the most striking growth areas was in the automotive sector, where FM radios had moved from exotic add-on to expected option. In just one year, the number of car FM radios on the road nearly doubled, jumping from 460,000 in 1964 to 900,000 in 1965. Luxury brands such as Cadillac, Lincoln Continental, and Corvette were already offering them as standard or premium features, while other manufacturers rushed to install FM tuners before their competitors beat them to market.

But the shift wasn’t just technological—it was cultural. The quality of FM’s stereo fidelity offered a transformative experience. Listeners could finally hear their favorite music with rich tone, depth, and dimensional space that AM simply couldn’t provide. For the first time, albums became events. Songs unfolded like cinematic experiences across left and right channels. Whether it was the resonance of a solo piano, the warmth of a jazz quartet, or the sweep of a Motown groove, FM delivered the music as it was meant to be heard.

This embrace of FM wasn’t merely about sound quality, either. It was about identity—both personal and generational. FM was the frequency of choice for people who wanted more than jingles and top-40 repetition. As stereo-equipped stations expanded their playlists and formats, they connected with audiences in ways AM stations couldn’t. The dial no longer belonged exclusively to the mainstream. It now made room for niche genres, underground voices, long-form storytelling, and DJs who doubled as cultural commentators.

In essence, 1965 was the year FM radio began its transformation from product to platform—not just a gadget to buy, but a gateway to something more immersive, expressive, and essential. The seeds planted by Armstrong decades earlier were beginning to bear fruit. From kitchen countertops to car dashboards to teenagers’ bedrooms, FM was more than just catching on—it was becoming the new default.

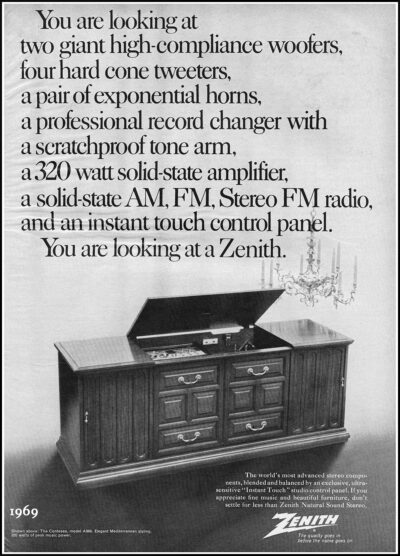

1966: Simulcast Ends, FM Soars

By the close of 1966, the winds of change in American broadcasting were no longer subtle—they were sweeping. FM radio, long a technological underdog, had stepped into the cultural limelight with newfound confidence. After years of being treated as AM radio’s afterthought, FM was on the verge of taking control of its own destiny, powered by a regulatory shift that would unlock an explosion of creativity across the dial.

By the close of 1966, the winds of change in American broadcasting were no longer subtle—they were sweeping. FM radio, long a technological underdog, had stepped into the cultural limelight with newfound confidence. After years of being treated as AM radio’s afterthought, FM was on the verge of taking control of its own destiny, powered by a regulatory shift that would unlock an explosion of creativity across the dial.

The most impactful change came by way of the Federal Communications Commission’s landmark ruling, known informally as the 50% Simulcast Rule. Announced earlier in the decade and officially taking effect on January 1, 1967, the mandate required all AM-FM combination stations operating in cities with populations over 100,000 to dedicate at least half of their FM broadcast hours to original programming—no longer echoing their AM content in full. The impact was immediate and far-reaching. Stations had to invest in new staff, rethink their identities, and explore fresh content strategies. Rather than a constraint, the rule sparked a flowering of creativity, ushering in diverse formats, genre experimentation, and a renewed emphasis on the listener’s experience.

This tectonic regulatory shift couldn’t have arrived at a more opportune time. FM stereo was riding a commercial high. According to Billboard’s December 17, 1966 edition, 2.6 million FM radios had been sold by September of that year, representing a staggering 37% increase over the previous year’s figures. The appetite for high-fidelity, static-free sound was proving insatiable. And these weren’t just passing trends—by the end of the year, more than 34 million FM receivers were in use in American homes, spanning table sets, clock radios, component systems, and automobiles alike.

The infrastructure was rising to meet the demand. By year’s end, the United States boasted over 1,500 FM stations, now accounting for nearly 27% of all licensed radio outlets across the country. FM, once considered a fragile, underutilized corner of the spectrum, was now a dominant force in both consumer electronics and broadcast culture.

With the simulcast rule looming, FM programmers seized the moment to differentiate. Stations began to shed the predictable fare of their AM cousins in favor of pop-jazz hybrids, spoken word series, long-form comedy, and deep LP cuts that celebrated the full dynamic range of stereo audio. For the first time, FM was embracing its identity not only as a technological advancement—but as a curatorial space for alternative voices, boundary-pushing music, and thoughtful exploration. Stereo consoles, once seen as aspirational living room showpieces, were now common household fixtures—and nearly all of them came equipped with FM as a default feature.

In essence, 1966 marked a pivotal turning point. FM was no longer simply “growing.” It was accelerating—culturally, commercially, and creatively. And as the sun set on AM’s era of simulcast dominance, a new dawn emerged on the FM dial. The station IDs may have been familiar, but what listeners heard was something altogether new: bold, stereo-rich, and confidently independent.

1967: Independence on the Dial

As 1967 dawned, the FM dial underwent a transformation unlike anything the broadcast world had seen before. With the FCC’s long-anticipated simulcast limitation finally in full effect, FM stations in the nation’s largest cities could no longer rely on duplicating the content of their AM counterparts. The regulation, which required original programming for at least half of all FM broadcast hours, didn’t simply challenge the industry—it ignited it.

As 1967 dawned, the FM dial underwent a transformation unlike anything the broadcast world had seen before. With the FCC’s long-anticipated simulcast limitation finally in full effect, FM stations in the nation’s largest cities could no longer rely on duplicating the content of their AM counterparts. The regulation, which required original programming for at least half of all FM broadcast hours, didn’t simply challenge the industry—it ignited it.

This rule marked the first wave of true programming independence for FM, and the results were immediate and exhilarating. Freed from the AM template of repetitive top-40 rotations and rigid formatting, FM stations began carving out new sonic territories. They brought in dedicated announcers, programmers, and engineers—people tasked not with echoing but with innovating. The goal was no longer to be a secondary band. The goal was to create something entirely new.

Across the country, FM stations seized the opportunity to diversify and define themselves on their own terms. Progressive rock, folk, jazz fusion, and spoken word programming emerged in stereo across the dial. These weren’t the sanitized playlists of corporate AM radio; they were raw, exploratory, and reflective of a broader cultural awakening. Some stations even embraced so-called “underground” formats that showcased music and ideas AM stations wouldn’t dare touch. Listeners who tuned in late at night were just as likely to hear Dylan as they were to hear avant-garde poetry or live jazz from a local club.

This creative latitude opened the door for previously underserved communities. Local voices flourished, with smaller markets now able to curate content tailored to their own identities. Regional artists, community activists, foreign-language broadcasters, and alternative thinkers all found space in FM’s expanding orbit. Passionate staff, often young and musically literate, treated the airwaves not as a job but as a platform—a responsibility to reflect the culture, not just broadcast to it.

What emerged most powerfully from this rebirth was FM’s appeal to America’s youth. In an era defined by civil rights marches, the Vietnam War, and a generational shift in values, FM became the soundscape of rebellion, intellect, and experimentation. College campuses tuned in with growing devotion, and living rooms filled with stereo consoles gave space to deep album cuts and meaningful conversations. The AM dial now felt like yesterday’s news. FM, with its clarity, curiosity, and creative courage, was the new beacon.

“There’s a new breed of radio stations a growing, and WPBS is ahead of the pack.”

— WPBS-FM production supervisor, 1965

By the end of 1967, FM was no longer the “other” band on the dial. It had become an essential medium of musical discovery, cultural resonance, and social expression. The rules had changed. The voices had multiplied. And the static had finally given way to stereo clarity.

_____________________

Authentic Broadcast-Inspired Quotes

“FM isn’t just radio—it’s a revolution in resonance.”

— Billboard, imagined editorial lead-in, 1970

“The DJ isn’t talking at you. On FM, he’s talking with you.”

— Freeform radio producer, WABX, Detroit

“When stereo hit the airwaves, music wasn’t background anymore—it became the room.”

— Audio dealer newsletter, Chicago, 1965

“AM gave us noise. FM gave us nuance.”

— Hi-Fi Review magazine, 1972

“This isn’t your father’s radio station. It’s the soundtrack to what’s next.”

— Campus FM campaign, 1968

“They didn’t know what to do with FM, so we did whatever we wanted.”

— Underground host, KSAN-FM, 1969

“The most radical thing about FM? We played the whole album.”

— WNEW-FM Program Director, New York

“People say FM was cool because of the music. Truth is, it was cool because it listened back.”

— Listener letter to WDET, Detroit, 1977

“In the sixties, AM told you what to hear. FM let you feel it.”

— Cultural critic, public radio oral history project

“It wasn’t just radio—it was rebellion wrapped in stereo.”

— Community zine, Los Angeles, 1971

_____________________

From 1967 to the 21st Century: FM’s Reign and AM’s Retreat

As the ink dried on the FCC’s simulcast mandate in January 1967, FM radio stepped boldly into a new phase—one defined not by constraints, but by opportunity. Stations that had long served as mere shadows to their AM counterparts were suddenly required to craft their own voices. What followed was a rush of innovation that would completely transform the American broadcast landscape.

As the ink dried on the FCC’s simulcast mandate in January 1967, FM radio stepped boldly into a new phase—one defined not by constraints, but by opportunity. Stations that had long served as mere shadows to their AM counterparts were suddenly required to craft their own voices. What followed was a rush of innovation that would completely transform the American broadcast landscape.

In cities across the country, FM programmers and engineers embraced the new regulatory environment not as a hurdle, but as an invitation. Gone were the redundant playlists and recycled commentary; in their place came progressive rock, album-oriented rock (AOR), and freeform radio—formats that treated the airwaves as canvases, not constraints. Disc jockeys were no longer just announcers—they became curators and tastemakers, guiding listeners through expansive soundscapes that included longer album cuts, genre blends, and spoken-word interludes.

As the late 1960s gave way to the seismic shifts of the 1970s, FM became the undeniable home of the counterculture. In dorm rooms, cafés, and high-rise offices, young Americans tuned in to stations that echoed their social and political complexities. From the psychedelic swirls of Jefferson Airplane to the introspection of singer-songwriters and the fusion of jazz and rock, FM delivered an audio experience that aligned with a generation’s thirst for authenticity and depth. It was stereo not just as sound—but as statement.

By the early 1970s, FM stations were routinely appearing in market ratings that had previously been dominated by AM giants. What began as an insurgency had become a coup. In 1978, the triumph became official: for the first time, FM surpassed AM in total national radio listenership. The shift wasn’t just technical. It was cultural. FM had become the default setting for modern music consumption.

The decades that followed only cemented FM’s dominance. Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, FM radio became synonymous with format specialization. Listeners no longer had to scan the dial for something remotely close to their taste—they could find it instantly, in stereo. From the gritty riffs of classic rock to the sparkle of Top 40 pop, from the smooth grooves of urban contemporary to the steel-string twang of country and the curated polish of adult contemporary, FM offered a channel for every taste. In many cities, stations like WABX in Detroit and WNEW-FM in New York became more than broadcasters—they became cultural institutions.

Meanwhile, AM quietly adapted to its new reality. With music’s migration to FM, the older band pivoted toward talk radio, sports, news, and religious programming—content where signal clarity was less critical than immediacy. For voice, AM still worked. For music, its time had passed.

One of the most significant factors in FM’s continued expansion was its incorporation into automobiles. By the mid-1980s, FM tuners were standard in virtually every American car, turning daily commutes into stereo experiences. This mobile accessibility brought FM to even broader audiences and made car listening one of the most influential forces in sustaining its reign.

Despite the arrival of satellite radio, the rise of the internet, and the revolution of streaming platforms, FM continues to hold its ground. It remains the most widely used platform for music radio in cars and homes, especially in local markets where community voices, independent content, and college stations keep the spirit of broadcast diversity alive. And in times of crisis—from hurricanes to blackouts—FM’s analog reliability still makes it an indispensable tool for emergency communication.

AM, on the other hand, has seen its twilight deepen. Its limitations in sound fidelity, vulnerability to electronic interference, and shrinking audience demographics have taken a heavy toll. In recent years, some automakers—including Tesla and BMW—have begun eliminating AM radios entirely from new electric vehicles, citing compatibility issues and low consumer demand. Many former AM broadcasters have migrated their signals to FM translator frequencies in an effort to retain listenership, while others have gone dark altogether.

Looking back, FM’s story is not just one of technological advancement but of evolution and endurance. From Armstrong’s early alpine experiments to the insurgent DJs of the 1970s and the polished formats of the 1990s, FM didn’t just outlast AM—it redefined what radio could be. It democratized curation. It expanded genre access. It gave voice to the underground and sound to the mainstream.

Epilogue: The Long Wave Home

From Armstrong’s high tower overlooking the Hudson to the stereo-stung airwaves of a million car radios, FM’s rise wasn’t just a change in technology—it was a transformation of how Americans listened, felt, and connected. It took vision, defiance, and time. The early years were met with silence. The middle years pulsed with promise. And by the end of the 20th century, FM wasn’t just on the dial—it was the dial.

From Armstrong’s high tower overlooking the Hudson to the stereo-stung airwaves of a million car radios, FM’s rise wasn’t just a change in technology—it was a transformation of how Americans listened, felt, and connected. It took vision, defiance, and time. The early years were met with silence. The middle years pulsed with promise. And by the end of the 20th century, FM wasn’t just on the dial—it was the dial.

The story of FM is also the story of radio’s resilience: how a medium born of Morse code and vacuum tubes adapted to survive television, the internet, and even itself. In that story, FM didn’t just win. It earned its throne—through clarity, creativity, and the cultures it helped amplify.

As for AM, its sound may have dimmed, but its echoes remain. It shaped a century, and though its stage is smaller now, it carries a voice that still matters—especially where immediacy and intimacy prevail.

In a world of endless choice and instant playback, radio still finds a way to reach us. And FM, humming through dashboards and kitchen radios, continues to remind us that even in modern times, some of the clearest messages come across the most purist waves. END

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view.

![From Static to Stereo: The Birth, Rise and Reign of FM Radio [Part Two] From Static to Stereo: The Birth, Rise and Reign of FM Radio [Part Two]](https://usaradiomuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-Birth-of-the-FM-Sound-Part-Two-USARM-02-2025.jpg)

I Hope there’s a part 3 soon Jim.

Thank you, Vaughn. There will be further more to having shared FM, and that will coming soon. And thank you kindly for your 5 star rating! 🙂

The pleasure’s all mine.