Connie Francis Dies at 87 — A Nation Mourns Its Voice July 17, 2025 — Fort Lauderdale, FL The USA Radio Museum mourns today the passing of l

Connie Francis Dies at 87 — A Nation Mourns Its Voice

July 17, 2025 — Fort Lauderdale, FL

The USA Radio Museum mourns today the passing of legendary vocalist Connie Francis, who died peacefully last night at the age of 87. The news was shared early this morning by longtime friend and Concetta Records president Ron Roberts, who stated, “I know that Connie would approve that her fans are among the first to learn of this sad news.”

Francis had been hospitalized earlier this month with extreme pain, undergoing tests and sharing updates with fans from her hospital bed. Her final public message, posted on July 4, read: “Today I am feeling much better after a good night, and wanted to take this opportunity of wishing you all a happy Fourth of July.”

Just weeks ago, she was celebrating the viral resurgence of her 1962 single “Pretty Little Baby” on TikTok, connecting with a new generation of fans and expressing heartfelt gratitude for the unexpected revival. “To think that a song I recorded 63 years ago is captivating new generations of audiences is truly overwhelming,” she wrote.

Her death marks the end of an era—but not the end of her voice. Connie Francis leaves behind a legacy of resilience, emotional truth, and musical brilliance that shaped American pop culture across decades.

_____________________

America’s Songstress: The Rise, Endurance of a Pop Icon

Born Concetta Rosa Maria Franconero on December 12, 1937, in Newark, New Jersey, Connie Francis rose from modest beginnings to become one of the most successful and beloved vocalists of the 20th century. With her crystalline voice and emotional sincerity, she captured the hearts of millions during the golden age of American pop. Her breakout hit “Who’s Sorry Now” in 1958 launched a career that would span decades, languages, and continents. By the age of 25, she had sold over 40 million records in the United States, and her global sales would eventually exceed 200 million, making her one of the best-selling female artists of all time.

Born Concetta Rosa Maria Franconero on December 12, 1937, in Newark, New Jersey, Connie Francis rose from modest beginnings to become one of the most successful and beloved vocalists of the 20th century. With her crystalline voice and emotional sincerity, she captured the hearts of millions during the golden age of American pop. Her breakout hit “Who’s Sorry Now” in 1958 launched a career that would span decades, languages, and continents. By the age of 25, she had sold over 40 million records in the United States, and her global sales would eventually exceed 200 million, making her one of the best-selling female artists of all time.

Connie’s artistry extended far beyond chart success. She recorded in more than a dozen languages, starred in multiple MGM musicals, and became a fixture on The Ed Sullivan Show, appearing 26 times. Her voice resonated across cultures, offering comfort, joy, and emotional truth. Despite facing unimaginable personal tragedies—including assault, vocal injury, and the loss of her brother—Connie returned to music with resilience and grace.

The early 1960s weren’t just Connie Francis’s prime—they were her canvas. At a time when American pop was navigating the tender shift between postwar optimism and youthful rebellion, Connie’s music landed with clarity, vulnerability, and daring sincerity. She wasn’t chasing trends. She was articulating feeling—something far more timeless.

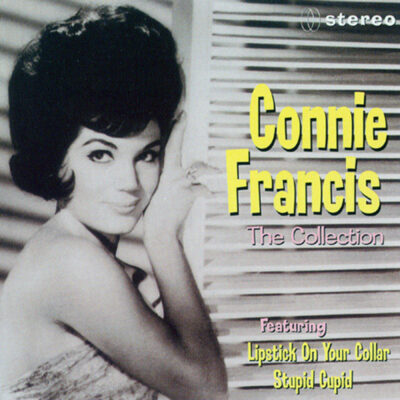

“Stupid Cupid,” co-written by Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, was a playful takedown of teenage infatuation. With its driving beat and cheeky vocals, it gave young listeners license to mock their own romantic stumbles. Connie didn’t perform from a pedestal—she performed from within their experiences. It’s what made songs like “Lipstick on Your Collar” so compelling. She sang betrayal not with bitterness, but with brisk resolve and infectious rhythm, validating every listener who’d glimpsed a name they didn’t recognize on their partner’s jacket.

Then came “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool.” Released in 1960, the track soared to No. 1 and made Connie the first solo female artist to top the Billboard Hot 100. She hadn’t just arrived—she had rewritten the rules. Her voice—emotive, crystalline, unafraid—proved that music didn’t need bombast to be powerful. Her delivery of heartbreak, especially on songs like “Don’t Break the Heart That Loves You” and “Many Tears Ago,” felt like confessions whispered across dance floors and quiet bedrooms.

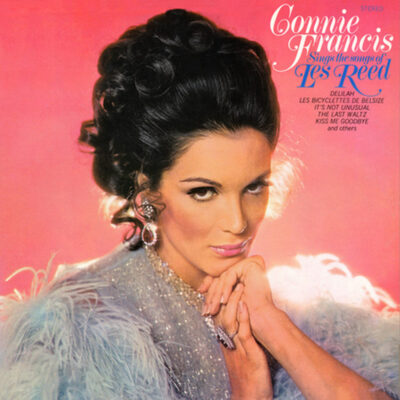

Collaborations with Sedaka and Greenfield weren’t rare—they were carefully chosen. Connie had an ear not just for melody but for meaning. She handpicked songs that told stories, that mirrored real emotions. Even her foreign-language recordings weren’t exercises in novelty—they were gestures of intimacy. “Die Liebe ist ein seltsames Spiel,” her German version of “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool,” became the best-selling single of 1960 in Germany. Her fans heard not just the notes, but the effort—the reverence for language, culture, and connection.

She wasn’t just a singer—she was a curator of emotional truth.

And those truths came back to her. In handwritten letters, gifted mementos, whispered stories passed from mothers to daughters. A woman once shared that “Where the Boys Are” was the song she danced to the night she met her husband. Another recalled playing “Mama” on loop when her own mother lay dying. Connie’s catalog became more than music—it became a quilt of shared memories.

Radio DJs recognized it early. They played the B-sides as often as the hits, knowing that a Francis flip side was never filler—it was often the soul of the single. Fans treasured both equally. Her records weren’t just collections—they were emotional passports.

By 1963, Connie had recorded more than 70 singles, appeared regularly on television, and starred in motion pictures. Yet her appeal remained intimate. Whether performing for troops in Guantanamo Bay or recording “In the Summer of His Years” in mourning for President Kennedy, she sang with a sense of collective emotion. Her voice was adaptable—not stylistically, but empathetically. It rose to meet the moment, whatever the moment needed.

Even her physical presence defied industry norms. She was petite, expressive, often dressed modestly compared to her contemporaries. She didn’t rely on spectacle—she relied on sincerity. Her eyes spoke as much as her vocals did. Audiences believed her because she believed them.

In time, Connie would be eclipsed on the charts by rock icons, psychedelic adventurers, and singer-songwriters who defined their own eras. But her songs endured. Not because they resisted change—but because they never pretended to be anything other than what they were: honest, emotional, and profoundly human.

Connie Francis sang her way into history not by striving for it—but by singing straight into the heart of it.

Where the Boys Are—and Beyond

In the winter of 1960, Connie Francis stepped into a new spotlight—not just as a singer, but as a screen presence. Cast as Angie in Where the Boys Are, she played a college girl navigating the thrills and uncertainties of spring break in Fort Lauderdale. The film, a coming-of-age dramedy, was more than a beachside romp—it was a cultural snapshot of shifting gender roles, youthful rebellion, and the emotional terrain of young adulthood. And Connie, with her signature blend of innocence and emotional depth, anchored it with grace.

In the winter of 1960, Connie Francis stepped into a new spotlight—not just as a singer, but as a screen presence. Cast as Angie in Where the Boys Are, she played a college girl navigating the thrills and uncertainties of spring break in Fort Lauderdale. The film, a coming-of-age dramedy, was more than a beachside romp—it was a cultural snapshot of shifting gender roles, youthful rebellion, and the emotional terrain of young adulthood. And Connie, with her signature blend of innocence and emotional depth, anchored it with grace.

The title track, written by Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, became a generational anthem. Connie recorded it in Italian, Spanish, French, German, and Japanese—all in a single New York City session in November 1960. That linguistic feat wasn’t just impressive—it was emblematic of her global reach. The song hit No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and soared to No. 1 in nineteen countries, cementing her status as an international star.

Her performance in the film was modest, but magnetic. She didn’t overact—she simply was. Angie wasn’t a stretch for Connie; she was a reflection. Earnest, curious, emotionally attuned. Critics noted that while she wasn’t trained as an actress, her authenticity made her scenes resonate. She wasn’t trying to be Hollywood—she was trying to be honest.

The success of Where the Boys Are led MGM to cast her in three more musicals:

- Follow the Boys (1963), filmed on location in the French and Italian Riviera, reunited her with Paula Prentiss and gave Connie a chance to showcase her romantic charm against a European backdrop.

- Looking for Love (1964), co-starring Jim Hutton and featuring a cameo by Johnny Carson, leaned into the bubbly optimism of the era.

- When the Boys Meet the Girls (1965), with Herman’s Hermits, was her final film—and one she later called “another lame Connie Francis movie” with characteristic self-deprecation.

Despite her success, Connie never felt at home in Hollywood. “I asked the studio why they couldn’t come up with a title without the word ‘boys’ in it!” she joked in a 2017 interview. She declined a role in the 1984 remake of Where the Boys Are, saying she was pleased that her last film had already been made.

But even as her star shone on screen, the shadows began to gather.

By the mid-1960s, the musical landscape was shifting. The British Invasion was in full swing. Rock was louder, edgier, more rebellious. Connie’s soft ballads and melodic pop began to feel out of step with the times. Her chart success waned. Her final Top 10 hit, “Vacation,” came in 1962. After that, the spotlight dimmed—but her emotional resonance never did.

Behind the scenes, her personal life was unraveling. A cosmetic surgery in 1967 damaged her vocal cords. She began to struggle with performance. And in 1974, after a concert in Westbury, New York, she was raped at knifepoint in her hotel room—a trauma that silenced her voice for years.

Her MGM musicals, once symbols of joy and youth, became bittersweet reminders of a time before the darkness. Connie later said, “I would like to be remembered, not so much for the heights I have reached, but for the depths from which I have come”.

And yet, even in the depths, she never stopped reaching.

_____________________

Sidebar: A Song for a Fallen President Connie Francis’s tribute to John F. Kennedy

Just days after the nation lost its 35th president, Connie Francis stepped into the studio—not as a pop star chasing charts, but as a citizen seeking solace. On December 2, 1963, she recorded “In the Summer of His Years”, a reflective, deeply felt tribute to John F. Kennedy, written by Herbert Kretzmer and David Lee.

Just days after the nation lost its 35th president, Connie Francis stepped into the studio—not as a pop star chasing charts, but as a citizen seeking solace. On December 2, 1963, she recorded “In the Summer of His Years”, a reflective, deeply felt tribute to John F. Kennedy, written by Herbert Kretzmer and David Lee.

Originally performed on the BBC by Millicent Martin in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, the song was tender and elegiac—its lyrics, almost whispered grief:

“A young man rode with his head held high / Under the Texas sun…”

Connie’s version, arranged by Claus Ogerman and released just days later by MGM Records, felt like a collective prayer. She didn’t over-sing. She didn’t dramatize. She simply allowed the ache to breathe through every note.

The single wasn’t released for commercial gain. Connie directed all proceeds to the family of J.D. Tippit, the Dallas police officer who was also killed on November 22, 1963 while confronting his killer. Though many radio stations hesitated to air the song—unsure if the public was ready—those who did described listeners moved to tears.

It peaked at #46 on the Billboard Hot 100, but the chart position was irrelevant. “In the Summer of His Years” was Connie Francis at her most compassionate, using her voice not to entertain, but to mourn.

She stood beside a grieving nation and sang what so many felt but couldn’t say.

_____________________

The Voice That Refused to Disappear

By the mid-1970s, Connie Francis had already etched her name into the annals of pop history. But fame, as it often does, offered no immunity from tragedy. In November 1974, after a performance at the Westbury Music Fair in Long Island, Connie checked into the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge nearby. What followed was a nightmare: she was raped at knifepoint, bound to a chair, and nearly suffocated beneath a mattress and suitcase. The assailant stole her jewelry and mink coat before fleeing. Though a suspect was detained, no conviction followed. The trauma was profound—and it silenced her.

Connie didn’t sing again for seven years. Not a note. Not a whisper. She withdrew from public life, battling severe depression, anxiety, and the crushing isolation of being a survivor in the public eye. “I didn’t grant a single interview,” she later said. “I had to process it all behind closed doors.” Fame, in that moment, became a barrier to healing.

Then came another blow: in 1977, a nasal surgery—intended to improve her breathing and vocal clarity—went horribly wrong. Her voice was gone. “Losing my voice was like a surgeon losing his hands,” she said. It was the ultimate cruelty for a woman whose identity was built on song.

Then came another blow: in 1977, a nasal surgery—intended to improve her breathing and vocal clarity—went horribly wrong. Her voice was gone. “Losing my voice was like a surgeon losing his hands,” she said. It was the ultimate cruelty for a woman whose identity was built on song.

And still, the tragedies mounted. In 1981, her brother George Franconero Jr. was murdered outside his New Jersey home, shot in the head while clearing ice from his car. George had been a federal informant, and many believed his death was a mob retaliation. Connie was shattered. But something unexpected happened: in her grief, she began to hum “Danny Boy” aloud—and her voice returned. Not perfectly. Not painlessly. But it came back. And with it, a flicker of hope.

Her mental health struggles, however, were far from over. Between 1982 and 1991, Connie was involuntarily committed to psychiatric institutions 17 times across five states. Misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder, ADD, and other conditions, she was prescribed lithium and other medications that left her feeling “like a zombie.” It wasn’t until years later that she was correctly diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder—a diagnosis that finally made sense of the chaos.

In 1984, she attempted suicide, swallowing sleeping pills and falling into a coma for three days. When she awoke, she chose to fight. That same year, she published her memoir, Who’s Sorry Now?—a raw, unflinching account of her suffering and survival. It wasn’t just a book. It was a declaration: I’m still here.

And then—she returned to the stage.

Her comeback wasn’t about reclaiming stardom. It was about reconnection. Connie began performing again, often in the native language of her audience. In Tokyo, she sang in Japanese. In Tel Aviv, in Hebrew. In Berlin, in German. These weren’t just concerts—they were acts of emotional generosity, moments of shared healing between artist and listener.

She became an advocate for victims’ rights, partnering with President Reagan’s administration on a task force for violent crime. In 2010, she became a national spokesperson for Mental Health America, using her platform to raise awareness about trauma, depression, and recovery. “I don’t want people to feel sorry for me,” she said. “I want them to know they can survive.”

Her later performances were quieter, more intimate. She sang with a voice that had been broken and rebuilt. She spoke openly about her past. And she never stopped thanking her fans—those who had waited, who had written, who had believed.

Connie Francis didn’t just survive. She transformed. Her voice, once silenced by violence, became a beacon for others. Her songs, once chart-toppers, became testimonies. And her life, once defined by glamour, became a story of grit, grace, and unshakable courage.

Sullivan’s Star: A Voice That Never Left the Room

In the golden age of television, few stages carried the cultural weight of The Ed Sullivan Show. It was where Elvis swiveled, The Beatles debuted, and America gathered around flickering screens to witness the pulse of pop culture. And there, time and again, stood Connie Francis—graceful, grounded, and emotionally true.

In the golden age of television, few stages carried the cultural weight of The Ed Sullivan Show. It was where Elvis swiveled, The Beatles debuted, and America gathered around flickering screens to witness the pulse of pop culture. And there, time and again, stood Connie Francis—graceful, grounded, and emotionally true.

Between her debut on May 11, 1958, and her final appearance on June 7, 1970, Connie performed on Sullivan’s stage 26 times, making her one of the show’s most frequent musical guests. That number alone speaks volumes. But it’s the why behind it that reveals her staying power.

Ed Sullivan didn’t just book stars—he booked voices that moved people. And Connie’s voice, with its aching clarity and emotional precision, did just that. Her debut performance of “I’m Sorry I Made You Cry” was tender and arresting, setting the tone for a relationship built on mutual respect. Ed saw in Connie what millions did: a singer who didn’t just perform—she connected.

Throughout the 1960s, as musical tastes shifted and rock ’n’ roll surged, Connie remained a fixture. She sang “Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing” in 1961, filmed live from West Berlin—a performance that showcased not just her vocal control, but her emotional command. She wasn’t trying to compete with the new wave—she was offering something timeless.

Her appearances weren’t just musical interludes—they were emotional events. In 1960, she performed “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” with the same sincerity that made it a No. 1 hit. In 1961, she delivered “Where the Boys Are” from Berlin, bridging continents with a song that had already become a cultural anthem. And in 1970, her final Sullivan performance featured a medley of “The Trolley Song,” “You Made Me Love You,” and “For Me and My Gal”—a nostalgic, emotionally layered farewell that felt like a curtain call for an era.

Even as her commercial peak faded, Ed Sullivan remained loyal. He invited her to perform for American troops in Guantanamo Bay and West Berlin, recognizing that her voice carried comfort, patriotism, and emotional truth. She wasn’t just a guest—she was a trusted presence, someone who could still make a nation pause and feel.

And Connie never took it for granted. She once said, “Ed gave me a place to sing when the world was changing faster than I could keep up. He let me be myself.” That self—earnest, elegant, emotionally fluent—was exactly what audiences needed.

Her final appearance in June 1970, featuring a medley that included “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” was more than performance—it was benediction. She sang not to impress, but to remind. That melody, that voice, that presence—it hadn’t disappeared. It had simply grown deeper.

Honors and Echoes: The Awards That Followed the Voice

Connie Francis didn’t need a shelf full of statuettes to prove her worth—but the honors she received across decades stand as echoes of a legacy that was cherished, profound, and international in scope.

In 1964, she was awarded a Golden Globe Special Achievement Award for her contributions to recorded music worldwide—a rare and fitting tribute to her power as a multilingual artist who bridged emotional divides across continents. That same year, she earned nominations in the Laurel Awards, a public vote-driven recognition honoring her musical performances in Follow the Boys, Looking for Love, and When the Boys Meet the Girls. Though she never took home the top prize, her consistent placement among the year’s favorites showed her unshakable connection with audiences.

Her global impact garnered special honors abroad: in Germany, where “Die Liebe ist ein seltsames Spiel” became a cultural phenomenon, Connie was nominated for the Echo Award for Best National Rock/Pop Female Artist in 1993. Even decades after her peak, international communities continued to celebrate her influence.

Connie was also inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame, a recognition granted to chart-dominating artists whose music endured beyond its moment. For Connie, it wasn’t just about numbers—it was about emotional reach.

In Hollywood, her legacy is etched in stone. A Hollywood Walk of Fame star was dedicated at 6381 Hollywood Boulevard, commemorating both her musical artistry and cinematic ventures. Fans still visit, tracing the letters of her name with quiet awe.

And while the Recording Academy never awarded her a Grammy, the absence says more about the institution than the artist. Connie topped the Billboard charts with emotional conviction, sold over 40 million records before age 25, and brought American pop into twelve languages with poise and sincerity. Her impact far outlived any single ceremony.

Connie Francis was not defined by awards. But when they came, they echoed what her fans knew all along: her voice was a gift—and her legacy, indelible.

Final Notes, Final Grace

In the final chapter of her life, Connie Francis did something extraordinary: she reminded the world that legacy isn’t just what you leave behind—it’s what you continue to give, even in your last days.

In the final chapter of her life, Connie Francis did something extraordinary: she reminded the world that legacy isn’t just what you leave behind—it’s what you continue to give, even in your last days.

Her health had been declining for some time. In early 2025, she began using a wheelchair to ease pressure on a painful hip, awaiting stem cell therapy and quietly managing discomfort that would later intensify. By June, she was undergoing tests for pelvic pain and was told she had a fracture. “It looks like I may have to rely on my wheelchair a little longer than anticipated,” she wrote to fans, always with a touch of grace.

Then, on July 2, she was hospitalized again—this time in intensive care. The pain was severe, and doctors struggled to locate its source. But Connie, ever the fighter, remained hopeful. She posted from her hospital bed:

“Today I am feeling much better after a good night, and wanted to take this opportunity of wishing you all a happy Fourth of July.”

It would be her final public message.

And yet, even as her body faltered, something miraculous was happening. Her 1962 B-side, “Pretty Little Baby,” a song she barely remembered recording, had gone viral on TikTok. It began in May, with creators using the track for everything from makeup tutorials to pet videos. Celebrities like Kylie Jenner, Kim Kardashian, North West, and even Agnetha Fältskog of ABBA joined in. The song exploded—over 1.8 million TikTok videos, 27 billion views, and a surge to No. 1 on the app’s Viral 50 and Top 50 charts.

Connie was stunned. She joined TikTok herself, posting a video on June 6 with her hand over her heart: “To think that a song I recorded 63 years ago is captivating new generations of audiences is truly overwhelming. Thank you, TikTok!”

She lip-synced to her own recording for the first time ever. The post garnered over three million likes, and even the official TikTok account commented: “LOVE YOU LEGEND!”

It was more than a trend—it was a resurrection. Kindergarteners were discovering her voice. Teenagers were dancing to her phrasing. And Connie, tucked away in her Florida home, was watching it all unfold with wonder. “It gives me a new lease on life,” she told Billboard in May.

Connie’s final notes weren’t sung on stage or pressed into vinyl. They were shared through screens, echoed in hashtags, and felt in hearts across generations. She didn’t chase relevance—she became it. And in doing so, she reminded us that true grace isn’t about how loudly you leave—it’s about how deeply you’re remembered.

Our Reflections: A Loving Farewell to Connie Francis

Connie Francis was never just a voice on the radio—she was the voice in the room. The one that played softly in the kitchen while mothers cooked. The one that echoed through transistor speakers on summer porches. The one that held your hand through heartbreak, and danced with you through joy. Her music didn’t just chart—it comforted. It connected. It endured.

Connie Francis was never just a voice on the radio—she was the voice in the room. The one that played softly in the kitchen while mothers cooked. The one that echoed through transistor speakers on summer porches. The one that held your hand through heartbreak, and danced with you through joy. Her music didn’t just chart—it comforted. It connected. It endured.

She was a living bridge—between generations, between cultures, between sorrow and celebration. Her voice carried the innocence of the 1950s, the emotional depth of the 1960s, and the hard-won wisdom of every decade that followed. And even in her final days, she was still reaching out—posting messages of hope, marveling at the TikTok revival of “Pretty Little Baby,” and reminding us that music, like memory, never fades.

At the USA Radio Museum, we don’t just preserve Connie’s records—we preserve her resonance. Her story lives in our archives, our playlists, our exhibits, and now, in this tribute. It belongs to every listener who found comfort in her lyrics, strength in her struggles, and joy in her radiant smile. It belongs to the girl who bought her first vinyl with babysitting money. To the father who played “Mama” for his children. To the survivor who saw in Connie’s courage a mirror of their own.

She taught us that vulnerability is not weakness. That melody can be medicine. That even after silence, a voice can return.

And so, we say goodbye not with sorrow, but with gratitude. For her songs. For her strength. For her story.

Connie Francis was—and remains—a part of our national soundtrack. And here, at the USA Radio Museum, her voice continues to resonate for the ages—through every exhibit, every echo, and every melody she beautifully sang.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view.