Introduction: Opening Paragraphs On the morning of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters at t

Introduction: Opening Paragraphs

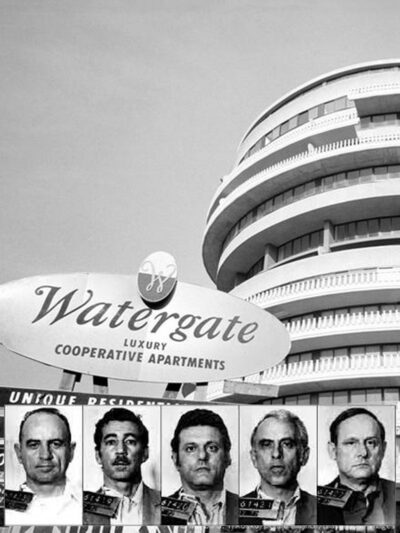

On the morning of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. What initially appeared to be a bungled burglary soon unraveled into the most seismic political scandal in American history—one that would ultimately lead to the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

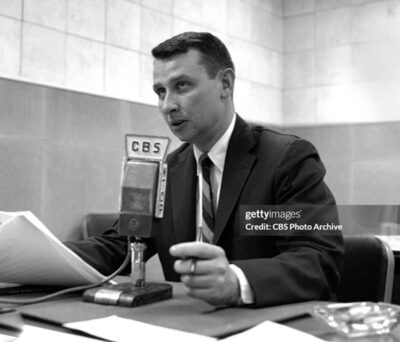

By the summer of 1973, the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities had become the nation’s moral compass, broadcasting daily revelations that exposed a web of deceit, surveillance, and abuse of power. Among those summoned to testify was former CIA Director Richard Helms, the U.S. Ambassador to Iran at the time, whose appearance on August 2, 1973, marked a critical moment in the hearings. His testimony, broadcast in a CBS Special Report anchored by Neil Strawser, offered a rare glimpse into the uneasy intersection of intelligence, politics, and accountability.

This article revisits that day in detail—drawing from archival audio, committee transcripts, and historical analysis—to explore how the CIA was drawn into the Watergate vortex, and how Helms’ testimony helped define the boundaries of institutional integrity in a time of national crisis. —USA Radio Museum

_____________________

I: Echoes of a Break-In: The Watergate Scandal Begins

In the early hours of June 17, 1972, a quiet hum of fluorescent light spilled across the marble floors of the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. Inside the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, five men—wearing business suits and surgical gloves—were caught rifling through files and planting surveillance equipment. They were arrested on the spot. What seemed like a clumsy burglary quickly revealed itself to be something far more sinister: a politically motivated operation tied to President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign. The men were part of a covert unit known as the “White House plumbers,” originally assembled to stop leaks of classified information, such as the Pentagon Papers. But their mission had evolved into political espionage. Among them was E. Howard Hunt, a former CIA operative turned White House aide, and G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent. Both had direct ties to Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP), often mockingly referred to as “CREEP.” As journalists like Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post began to dig deeper, they uncovered a trail of hush money, secret recordings, and obstruction of justice that led straight to the Oval Office. The scandal grew in scope and gravity, shaking the foundations of American democracy. By early 1973, the Senate had formed the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, chaired by Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina, to investigate the affair in full public view. The hearings were broadcast live, day after day, drawing millions of viewers. Americans watched as former aides, campaign officials, and government insiders testified under oath, revealing a culture of paranoia, surveillance, and political sabotage. The nation was transfixed—not just by the scandal itself, but by the slow, methodical unraveling of power. It was in this charged atmosphere that the former CIA Director Richard Helms was called to testify on August 2, 1973. His appearance was part of a broader inquiry into whether the CIA had been used—willingly or otherwise—to obstruct the FBI’s investigation into Watergate. Anchoring CBS’s coverage that day was Neil Strawser, whose calm, authoritative voice guided listeners through the labyrinth of intelligence, secrecy, and political fallout.

II. The Plumbers, the President, and the Plan

On September 24, 1973: E. Howard Hunt was publicly questioned about his activities and connections to the White House and intelligence agencies.

The Watergate break-in was not an isolated act—it was the culmination of a broader strategy born out of the Nixon administration’s obsession with secrecy and control. In 1971, following the leak of the Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg, the White House created a covert task force to plug information leaks. This unit, unofficially dubbed the “plumbers,” was staffed by men with intelligence backgrounds and a willingness to operate outside the bounds of legality. At the center of this operation was E. Howard Hunt, a veteran of the CIA’s clandestine service. Hunt had spent decades in the shadows—helping orchestrate the Bay of Pigs invasion, managing covert propaganda in Latin America, and mastering the art of psychological operations. By the time he joined the Nixon White House, Hunt was no longer a government employee, but his reputation and skillset made him an ideal candidate for off-the-books assignments. Working alongside G. Gordon Liddy, Hunt helped plan a series of break-ins and surveillance operations targeting political opponents and perceived threats. Their activities were sanctioned by top White House aides, including John Ehrlichman and Bob Haldeman, who saw the plumbers as a necessary tool in Nixon’s reelection arsenal. The Watergate burglary was just one of many operations. But it was the one that failed—and in failing, exposed the entire apparatus. When the burglars were caught, Hunt’s name surfaced quickly. Investigators discovered that he had requested disguises, false identification, and audio surveillance equipment from his former colleagues at the CIA. These requests, while not directly linked to Watergate, raised alarm bells. Had the CIA been involved in domestic political espionage? The Nixon administration moved swiftly to contain the damage. In the days following the arrests, White House officials attempted to use the CIA to block the FBI’s investigation, citing national security concerns. The goal was clear: redirect the probe away from the White House and toward a dead end. But the CIA resisted. Ex-Director Richard Helms, a career intelligence officer known for his discretion and loyalty to institutional norms, refused to play along. He understood the gravity of the request and the danger it posed to the agency’s credibility. Helms’ refusal marked a turning point—one that would eventually lead him to the witness chair before the Senate Watergate Committee.

III. Richard Helms Takes the Stand

On August 2, 1973, the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities convened for another day of testimony. But this time, the witness was not a campaign operative or White House aide. It was Richard Helms (currently Ambassador to Iran), the former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency—a man whose career had been built on silence, secrecy, and service to the nation’s most sensitive missions. Helms entered the chamber with the calm precision of a seasoned diplomat. He had served under multiple presidents, navigated Cold War crises, and overseen covert operations across the globe. But now, he faced questions not about foreign adversaries, but about the potential misuse of his agency by the very government it served. Senators pressed Helms on several fronts. Chief among them was the Huston Plan, a 1970 proposal crafted by White House aide Tom Charles Huston that called for expanded domestic surveillance, including mail openings, wiretaps, and break-ins. The plan had been rejected by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, but Huston claimed that Helms had initially expressed support. Helms denied this, stating that the CIA had no mandate to operate domestically and that he had voiced concerns from the outset. The committee also explored the CIA’s participation in an inter-agency intelligence evaluation committee, which some senators argued blurred the lines between foreign and domestic surveillance. Helms defended the agency’s role, emphasizing that its contributions were limited to foreign intelligence and that any domestic overlap was incidental, not intentional. But the most pointed questions centered on E. Howard Hunt. Helms acknowledged Hunt’s long tenure at the CIA and confirmed that Hunt had requested materials—disguises, voice alteration equipment, and false documents—from the agency in 1971 and 1972. These requests were granted, but Helms insisted they were unrelated to the Watergate break-in and were made under the guise of national security assignments. Still, the optics were troubling. Hunt had used his CIA credentials to lend legitimacy to covert White House operations. And when the Watergate scandal broke, White House officials attempted to use the CIA to obstruct the FBI’s investigation, claiming that further probing would compromise agency operations. Helms refused. In his testimony, Helms made it clear: the CIA had not participated in the Watergate burglary, nor had it sanctioned Hunt’s activities. He described the agency’s role as peripheral—drawn in by the gravity of the scandal, but not complicit in its execution. His words were measured, but firm. The CIA, he said, must remain outside the realm of domestic politics. CBS’s Neil Strawser, anchoring the network’s Special Report that day, captured the tension with quiet authority. “This is not a man accustomed to public scrutiny,” Strawser noted. “But today, Richard Helms speaks not as a spymaster, but as a guardian of institutional boundaries.” Helms’ testimony did not exonerate the CIA from all criticism. But it did reinforce a crucial principle: that even in times of political crisis, the nation’s intelligence apparatus must adhere to its legal and constitutional limits. It was a moment of quiet defiance—one that helped preserve the agency’s integrity amid the chaos of Watergate.

_____________________

Sidebar | From Langley to Tehran: Richard Helms’ Diplomatic Pivot

Richard Nixon appointed Richard Helms as U.S. Ambassador to Iran on April 5, 1973. This followed Helms’ departure from the CIA, where he had served as Director of Central Intelligence from 1966 until early 1973. The appointment was widely seen as a way to remove Helms from Washington amid growing tensions over Watergate and the CIA’s role in domestic matters.

Helms’ ambassadorship placed him at the heart of U.S.–Iran relations during the twilight of the Shah’s regime. With deep intelligence ties and diplomatic acumen, he navigated a volatile landscape, balancing official diplomacy with covert coordination. His tenure foreshadowed the seismic shifts that would soon reshape the region.

Helms served in Tehran until December 27, 1976, navigating a complex geopolitical landscape during the final years of the Shah’s reign. His ambassadorship was marked by both diplomatic finesse and continued involvement in sensitive intelligence coordination.

_____________________

IV. CBS Special Report: A Broadcast Chronicle

On August 2, 1973, as the former CIA Director Richard Helms took his seat before the Senate Watergate Committee, millions of Americans tuned in—not just through television, but through the steady, immersive voice of radio. Anchoring CBS’s Special Report that day was Neil Strawser, whose calm delivery and journalistic clarity helped guide listeners through the labyrinth of testimony, implication, and institutional drama. Strawser’s broadcast was more than a news update—it was a public reckoning. For thirty uninterrupted minutes, CBS Radio offered a front-row seat to one of the most consequential hearings in American history. The tone was sober, the pacing deliberate. Strawser framed Helms’ testimony not as a spectacle, but as a moment of democratic accountability. “Today, the nation’s top intelligence officer faces questions not about foreign threats,” Strawser intoned, “but about the integrity of government itself.” The broadcast captured the tension in the room: Helms’ measured responses, the senators’ pointed inquiries, and the underlying question of whether the CIA had been used as a political tool. Strawser contextualized each exchange, offering listeners historical background and editorial restraint. He reminded audiences of Hunt’s CIA past, the Huston Plan’s controversial origins, and the Nixon administration’s attempts to blur the lines between national security and political survival. For many Americans, especially those without access to television, radio was the lifeline to truth. The Watergate hearings were not just a Washington drama—they were a national experience, unfolding in real time across living rooms, car dashboards, and kitchen counters. CBS’s coverage, and Strawser’s anchoring in particular, helped translate the complexity of the hearings into a narrative the public could grasp. In retrospect, the August 2 broadcast stands as a testament to the power of journalism. It preserved a moment when institutional integrity was tested, and when one man—Richard Helms—chose to uphold the boundaries of his office rather than bend to political pressure. For the USA Radio Museum, this audio file is more than an artifact—it’s a sonic snapshot of democracy in action. As the broadcast concluded, Strawser offered a final reflection: “In a time of secrecy and suspicion, today’s testimony reminds us that even the most silent institutions must speak when the Constitution calls.”

_____________________

CBS Radio Network | Watergate Hearings Recap | Neil Strawser | August 2, 1973

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

Special Audio Source Acknowledgment

This recording is presented courtesy of the exceptional Past Daily website and is the property of its founder and curator, Gordon Skene, whose remarkable archive continues to preserve and share historic audio of lasting cultural significance. The featured broadcast—like many in Past Daily’s vast collection—was made freely available for streaming play and downloading in the earlier years of the site. During that period, the author acquired numerous historic recordings from Past Daily, several of which have been respectfully featured on the (former) Motor City Radio Flashbacks website over the years—to the site’s (and the owner’s) sole credit. Founded in 2012, Past Daily remains active and thriving online, dedicated to preserving and presenting audio history to a global audience. To support their ongoing mission and explore more of their archival treasures, please visit Past Daily—or simply click [HERE].

_____________________

V. Legacy and Lessons

Richard Helms’ testimony on August 2, 1973, did not dominate headlines in the way John Dean’s revelations or the “smoking gun” tape would. But its significance was profound. In a moment when the machinery of government was being twisted for political ends, Helms stood firm. He reminded the nation that even in the shadows of intelligence work, there are lines that must not be crossed. The CIA, long shrouded in secrecy, had been pulled into the Watergate scandal not by its own actions, but by the desperation of a White House in crisis. Helms’ refusal to obstruct justice, and his insistence on the agency’s legal boundaries, helped preserve its institutional integrity. It was a quiet act of resistance—but one that echoed loudly in the halls of Congress and the minds of the American public. For Nixon’s aides, the fallout was swift. Ehrlichman, Haldeman, and Mitchell were indicted and convicted. Nixon himself, facing near-certain impeachment, announced his resignation on August 8, 1974, becoming the first U.S. president to leave office voluntarily under the weight of scandal. The Watergate affair reshaped the presidency, the press, and the public’s understanding of accountability. And for journalism—especially broadcast journalism—Watergate was a defining moment. Radio and television brought the hearings into homes across the country, turning civic engagement into a shared experience. Anchors like Neil Strawser didn’t just report the news—they narrated the nation’s reckoning.

Richard Helms’ testimony on August 2, 1973, did not dominate headlines in the way John Dean’s revelations or the “smoking gun” tape would. But its significance was profound. In a moment when the machinery of government was being twisted for political ends, Helms stood firm. He reminded the nation that even in the shadows of intelligence work, there are lines that must not be crossed. The CIA, long shrouded in secrecy, had been pulled into the Watergate scandal not by its own actions, but by the desperation of a White House in crisis. Helms’ refusal to obstruct justice, and his insistence on the agency’s legal boundaries, helped preserve its institutional integrity. It was a quiet act of resistance—but one that echoed loudly in the halls of Congress and the minds of the American public. For Nixon’s aides, the fallout was swift. Ehrlichman, Haldeman, and Mitchell were indicted and convicted. Nixon himself, facing near-certain impeachment, announced his resignation on August 8, 1974, becoming the first U.S. president to leave office voluntarily under the weight of scandal. The Watergate affair reshaped the presidency, the press, and the public’s understanding of accountability. And for journalism—especially broadcast journalism—Watergate was a defining moment. Radio and television brought the hearings into homes across the country, turning civic engagement into a shared experience. Anchors like Neil Strawser didn’t just report the news—they narrated the nation’s reckoning.

Today, as the USA Radio Museum preserves the CBS Special Report from that pivotal day (and credit to the Past Daily website), it offers more than historical documentation. It offers a reminder: that truth, when spoken clearly and courageously, can pierce even the most fortified walls of power. The legacy of Watergate is not just in the downfall of a president. It’s in the resilience of institutions, the vigilance of the press, and the determination of former CIA Director Richard Helms to safeguard and protect the Agency–no matter the cost–when he chose institution’s principles over politics. As we listen to the echoes of August 2, 1973, we are reminded that democracy is not self-sustaining—it must be defended, even in silence.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view.