Pop Music’s Cultural Shift Streamlines 1954 Introduction: From Polished Pop to the Pulse of Change In 1953, America’s airwaves were still dresse

Pop Music’s Cultural Shift Streamlines 1954

Introduction: From Polished Pop to the Pulse of Change

In 1953, America’s airwaves were still dressed in tuxedos. The Hit Parade reigned supreme, delivering sanitized pop standards and crooner ballads that reflected a postwar appetite for order, elegance, and predictability. Perry Como, Patti Page, and Eddie Fisher topped the charts, their voices floating through living rooms like silk—safe, familiar, and largely segregated. But beneath that polished surface, a restless rhythm was building.

Then came 1954.

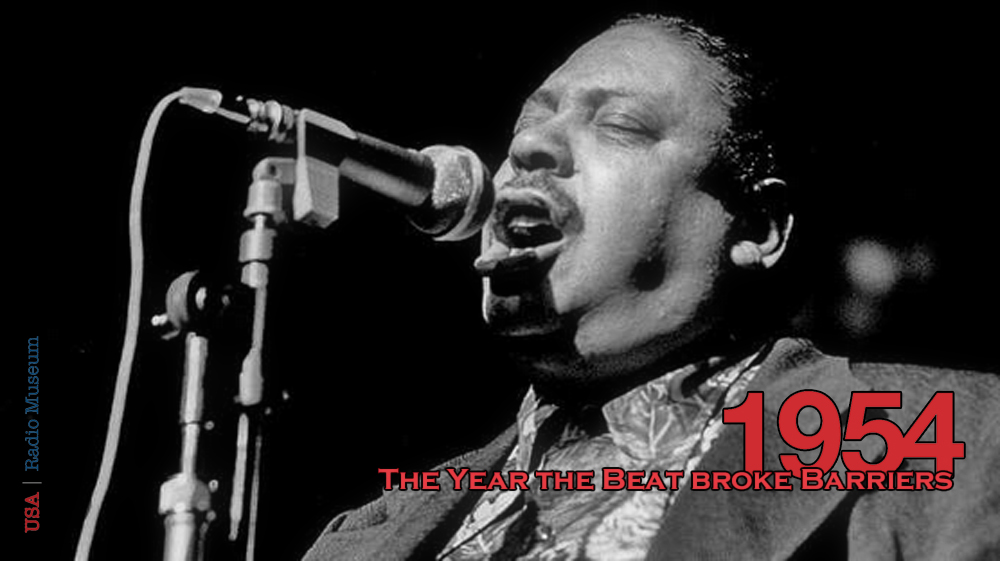

It was the year the beat got bigger, bolder, and undeniably Black. The year when rhythm and blues—long relegated to “Race Music” stations—crashed the gates of mainstream radio. With the rise of artists like Big Joe Turner, Clyde McPhatter, and a young Elvis Presley echoing those sounds, the cultural tectonics shifted. Rock ’n’ roll wasn’t just a new genre—it was a new language. And radio, once a gatekeeper of conformity, became the amplifier of rebellion, joy, and integration.

1954 didn’t just change the charts. It changed the soul of American music. — USA Radio Museum

_____________________

I. Prelude to a Revolution

Before the beat dropped, the world was waiting.

In the early 1950s, America’s soundscape was a lullaby of postwar comfort. Crooners like Perry Como and Eddie Fisher filled living rooms with velvet melodies, while orchestras and sentimental ballads soothed a nation still healing from global conflict. The music was safe, familiar, and deeply rooted in tradition. But beneath the polished surface, a restless energy was building—one that couldn’t be contained by sheet music or social norms.

In the early 1950s, America’s soundscape was a lullaby of postwar comfort. Crooners like Perry Como and Eddie Fisher filled living rooms with velvet melodies, while orchestras and sentimental ballads soothed a nation still healing from global conflict. The music was safe, familiar, and deeply rooted in tradition. But beneath the polished surface, a restless energy was building—one that couldn’t be contained by sheet music or social norms.

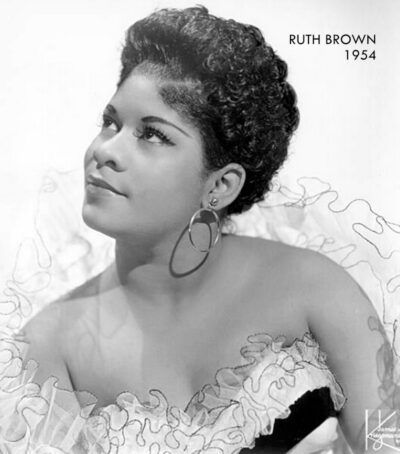

In Black communities across the country, rhythm and blues was already roaring. Artists like Ruth Brown, Big Joe Turner, and Wynonie Harris were electrifying local stages with raw vocals, pounding backbeats, and lyrics that spoke to real life—love, struggle, joy, and defiance. Gospel choirs raised the roof in sanctuaries, while country pickers strummed stories of heartbreak and grit. These genres weren’t just entertainment; they were expressions of identity, resistance, and soul.

Teenagers—newly minted as a cultural force—were tuning in. They didn’t want their parents’ music. They wanted something that matched their pulse, their rebellion, their desire to feel alive. The jukebox became a shrine to discovery. The transistor radio, a secret portal to forbidden sounds. And radio itself? It was the great equalizer. It didn’t care about zip codes or skin color. It carried voices across state lines and social boundaries, introducing white suburban kids to the electrifying sounds of Black America.

By 1954, the fuse was lit. The cultural ingredients were all there: racial tension, youthful rebellion, technological innovation, and a hunger for authenticity. What was missing was a name—a rallying cry. And that’s exactly what the year would deliver.

This was the year when music stopped asking for permission and started kicking down doors. The year when DJs became prophets, and a new sound—wild, rhythmic, unapologetic—began to echo across the country. It wasn’t just a genre. It was a movement. And it was about to change everything.

II. Alan Freed and the Naming of a Genre

The DJ who gave rock ’n’ roll its name—and its soul.

If 1954 was the year rock ’n’ roll found its voice, Alan Freed was the one who handed it the microphone. A former classical music announcer turned rhythm and blues evangelist, Freed didn’t just spin records—he spun culture. He saw what others missed: that the raw, driving energy of R&B wasn’t just a niche sound. It was the future.

If 1954 was the year rock ’n’ roll found its voice, Alan Freed was the one who handed it the microphone. A former classical music announcer turned rhythm and blues evangelist, Freed didn’t just spin records—he spun culture. He saw what others missed: that the raw, driving energy of R&B wasn’t just a niche sound. It was the future.

On January 14, 1954, Freed hosted the Rock ’n’ Roll Jubilee Ball at St. Nicholas Arena in New York City. The event was more than a concert—it was a declaration. For the first time, the term “rock ’n’ roll” was used publicly to describe a genre that fused rhythm and blues, gospel, country, and swing into something new, something electric. The phrase itself wasn’t new—it had long appeared in Black vernacular music—but Freed repurposed it, rebranded it, and broadcast it to the masses.

That same year, Freed moved from Cleveland’s WJW to New York’s WINS, bringing his Moondog Show to a national audience. His playlists were unapologetically integrated, featuring Black artists like LaVern Baker, Clyde McPhatter, and Joe Turner alongside white performers who were just beginning to emulate the sound. Freed didn’t just play the hits—he championed them. He introduced white teenagers to the music their parents tried to ignore, and he did it with swagger, slang, and a sense of mission.

Freed’s broadcasts were more than entertainment—they were cultural detonations. He blurred racial lines, challenged industry norms, and gave rock ’n’ roll its first real platform. His voice crackled through AM radios like a call to arms: This is your music. This is your moment.

In 1954, Alan Freed didn’t just name a genre. He baptized a movement.

Alan Freed | ‘The Moon Dog Show Rock ‘n’ Roll Party’ | WJW Cleveland | 1954

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

III. Bill Haley & His Comets: The Clock Strikes Twelve

The anthem that cracked the silence.

On April 12, 1954, inside the Pythian Temple studio in New York City, Bill Haley & His Comets recorded a song that would become the rallying cry of a generation: “Rock Around the Clock.” It wasn’t the first rock ’n’ roll record—not by a long shot—but it was the one that broke through the static and made the world listen.

On April 12, 1954, inside the Pythian Temple studio in New York City, Bill Haley & His Comets recorded a song that would become the rallying cry of a generation: “Rock Around the Clock.” It wasn’t the first rock ’n’ roll record—not by a long shot—but it was the one that broke through the static and made the world listen.

Released on May 20, 1954, as the B-side to “Thirteen Women (And Only One Man in Town),” the song didn’t make much noise at first. But its DNA was pure rebellion: a driving backbeat, a swinging guitar riff, and lyrics that promised freedom from the clock, from rules, from restraint. It was a party anthem disguised as a cultural manifesto.

Haley wasn’t a teen idol. He was a former country singer with a curl on his forehead and a band that blended Western swing with R&B grit. But his sound was infectious. It had bounce, swagger, and a sense of urgency that mirrored the mood of postwar youth. “Rock Around the Clock” didn’t just invite dancing—it demanded it.

Though the song’s true explosion came in 1955, when it was featured in the opening credits of Blackboard Jungle, its 1954 recording marked a turning point. It proved that rock ’n’ roll could be recorded, packaged, and sold to the masses. It gave radio stations a new kind of hit—one that crossed racial and generational lines. And it gave teenagers their first anthem.

Bill Haley didn’t invent rock ’n’ roll. But in 1954, he gave it a voice loud enough to shake the rafters.

IV. Elvis Presley’s First Recording: The Birth of a Star

From Tupelo to Memphis, the moment the world met Elvis.

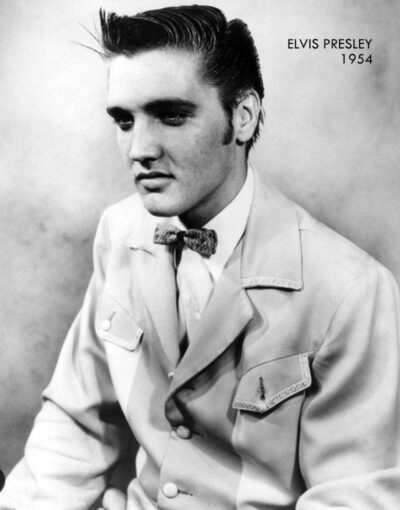

It was July 5, 1954, and the air inside Sun Studio in Memphis was thick with possibility. Sam Phillips, the visionary producer who believed “if I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars,” had just found his answer. His name was Elvis Presley.

It was July 5, 1954, and the air inside Sun Studio in Memphis was thick with possibility. Sam Phillips, the visionary producer who believed “if I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars,” had just found his answer. His name was Elvis Presley.

Presley had wandered into Sun months earlier to cut a personal acetate—just a shy kid with a guitar and a voice that didn’t quite fit any mold. But on that July night, something clicked. Backed by guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black, Elvis launched into a loose, rollicking version of Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right.” It wasn’t planned. It wasn’t polished. But it was electric.

Phillips knew instantly: this was the sound. A fusion of country twang, blues grit, and gospel soul, delivered with a swagger that felt both innocent and rebellious. He rushed the recording to local DJ Dewey Phillips, who played it on his Red, Hot & Blue show just two days later. The phone lines lit up. Teenagers called in. Parents called in. Everyone wanted to know: Who is this?

On July 19, “That’s All Right” was released as Elvis’s debut single. It didn’t chart nationally, but in Memphis, it was a phenomenon. By October 16, Elvis made his first appearance on Louisiana Hayride, a radio broadcast that would become his proving ground. Unlike the Grand Ole Opry, which turned him away, Hayride embraced him—and gave him a stage to grow.

Elvis didn’t invent rock ’n’ roll. But in 1954, he embodied its promise: a new kind of star, born not of polish but of passion. His voice was raw, his moves unrefined, but his presence was magnetic. He was the sound of something breaking loose.

And radio was the amplifier.

V. Radio’s Role in the Rock ’n’ Roll Uprising

The medium that made the message.

In 1954, rock ’n’ roll didn’t have a record label empire or a polished PR machine. What it had was radio—and radio was enough. Across the country, a new breed of disc jockeys was breaking rules, spinning records that defied segregation, and speaking directly to the youth who craved something real.

In 1954, rock ’n’ roll didn’t have a record label empire or a polished PR machine. What it had was radio—and radio was enough. Across the country, a new breed of disc jockeys was breaking rules, spinning records that defied segregation, and speaking directly to the youth who craved something real.

Dewey Phillips was one of the first. Broadcasting from WHBQ in Memphis, his Red, Hot & Blue show was a chaotic, joyful explosion of rhythm and blues, gospel, and country. He didn’t care about race—he cared about sound. When he played Elvis Presley’s “That’s All Right” in July 1954, he didn’t even mention that Elvis was white. He let the music speak.

Hunter Hancock in Los Angeles and Jocko Henderson in Philadelphia were doing the same—bringing Black artists into white homes, and vice versa. These DJs weren’t just trendsetters. They were cultural translators, bridging communities through rhythm and rebellion. They spoke in slang, shouted over the records, and made every broadcast feel like a party you didn’t want to miss.

Stations like WINS in New York, WDIA in Memphis, and KDAY in Los Angeles became sanctuaries for the new sound. Late-night shows, regional playlists, and underground broadcasts gave airtime to artists like Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and Fats Domino—voices that mainstream America hadn’t yet learned to embrace.

Radio gave rock ’n’ roll its wings. It bypassed gatekeepers, crossed state lines, and turned local hits into national anthems. It was intimate, immediate, and deeply personal. You didn’t just hear the music—you felt it, through the crackle of the signal and the voice of the DJ who made you believe it was yours.

In 1954, radio wasn’t just a platform. It became the pulse of a new revolution in sound.

VI. “Race Music” and the Sound That Shook the System

The rhythm that refused to be silenced.

Before rock ’n’ roll had a name, before Elvis walked into Sun Studio, before Bill Haley struck the clock—there was “Race Music.” That was the industry’s term for the vibrant, soul-deep sounds created and performed by Black artists: rhythm and blues, gospel, jazz, boogie-woogie, and early doo-wop. It was music born of struggle, joy, resistance, and truth. And in 1954, it was the heartbeat of a cultural reckoning.

Before rock ’n’ roll had a name, before Elvis walked into Sun Studio, before Bill Haley struck the clock—there was “Race Music.” That was the industry’s term for the vibrant, soul-deep sounds created and performed by Black artists: rhythm and blues, gospel, jazz, boogie-woogie, and early doo-wop. It was music born of struggle, joy, resistance, and truth. And in 1954, it was the heartbeat of a cultural reckoning.

Major record labels refused to record it. White-owned establishments wouldn’t stock it in jukeboxes. Radio stations often ignored it—unless it was covered by white performers. But the music couldn’t be contained. It was too powerful, too honest, too alive. Artists like Big Joe Turner, Ruth Brown, Clyde McPhatter, and Fats Domino were already crafting the sound that would become rock ’n’ roll—long before the genre had a name.

Alan Freed’s decision to play original Black recordings on his Cleveland show was revolutionary. He didn’t just spin records—he spun the cultural axis. White teenagers began clamoring for the music their parents called “race music.” And in doing so, they began to dismantle the walls of segregation—one song at a time.

Concerts by Black artists became sites of quiet rebellion. In the Jim Crow South, Black and white kids danced together, defying social norms and legal boundaries. The music was polarizing, yes—but only because it was transformative. It exposed the hypocrisy of segregation, challenged the sanitized narratives of mainstream pop, and gave voice to the voiceless.

By 1954, Black music wasn’t just influencing rock ’n’ roll—it was defining it. The rhythms, the vocal stylings, the lyrical themes—they were all rooted in African American musical traditions. And while the industry tried to whitewash the sound, the soul remained unmistakably Black.

“Race Music” was never just a label. It was a warning to the establishment—and a promise to the future. It said: You can’t silence this. You can’t stop this. You can only join the dance.

VII. The Sound of Change: Technology and Instruments

Electricity meets emotion.

If rock ’n’ roll was a cultural explosion, then 1954 was the year its sonic blueprint was drafted. The music didn’t just change hearts—it changed hardware. And at the center of that transformation was the electric guitar.

In 1954, Leo Fender introduced the Fender Stratocaster, a sleek, contoured marvel that would become one of the most iconic instruments in rock history. With its three-pickup configuration, tremolo arm, and futuristic design, the Stratocaster wasn’t just a guitar—it was a statement. It allowed players to bend notes, create feedback, and sculpt tones that had never been heard before. It gave rock ’n’ roll its growl, its shimmer, its scream.

Amplifiers followed suit. Tube-driven beasts like the Fender Bassman and Gibson GA-40 began shaping the sound with warmth, distortion, and punch. Reverb units added space and drama, while slapback echo—popularized in Sun Studio recordings—gave vocals a haunting, rhythmic bounce. These weren’t just effects. They were emotional tools, helping artists translate feeling into frequency.

Drums got louder. Bass lines got bolder. Recording studios began experimenting with mic placement, tape saturation, and overdubbing. The technology wasn’t just catching up to the music—it was chasing it, trying to keep pace with the urgency and innovation pouring out of every garage, club, and radio station.

In 1954, the sound of rock ’n’ roll wasn’t just born—it was engineered. And every knob turned, every string bent, every echo chamber activated helped shape the soundtrack of rebellion.

VIII. Cultural Impact and Legacy

When the music changed, everything else followed.

By the end of 1954, something had shifted. The songs weren’t just catchy—they were catalytic. Rock ’n’ roll wasn’t background noise anymore. It was front and center, reshaping identity, community, and the very idea of youth.

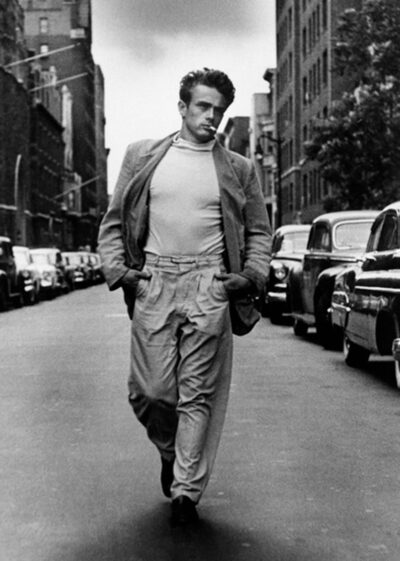

Teenagers, once seen as transitional figures between childhood and adulthood, suddenly had a soundtrack—and with it, a sense of self. “Rock Around the Clock” and “That’s All Right” weren’t just hits; they were declarations. The music gave voice to rebellion, romance, and raw emotion. It was loud, fast, and unfiltered—everything postwar conformity wasn’t.

And it wasn’t just about age. It was about race. Rock ’n’ roll was born from Black musical traditions—rhythm and blues, gospel, jazz—and carried forward by artists who had long been denied mainstream recognition. In 1954, radio began to crack those barriers. DJs played integrated playlists. White kids danced to Black voices. The music didn’t erase segregation, but it challenged it—one beat at a time.

Fashion changed. Language changed. Attitudes shifted. The pompadour became a symbol. The leather jacket, a badge. The dance floor, a battleground for freedom of expression. Rock ’n’ roll wasn’t just a genre—it was a cultural accelerant.

And the legacy? It’s still unfolding. Every guitar riff, every rebellious lyric, every festival stage owes something to 1954. It was the year the fuse was lit. The year the walls began to shake. The year music stopped being polite and started being powerful.

IX. Closing Reflection: Why 1954 Still Matters

The year the silence broke.

1954 wasn’t just a turning point—it was a reckoning. It was the year music stopped whispering and started roaring. The year when rhythm and blues collided with country twang, gospel soul, and teenage rebellion to form something utterly new. Something that couldn’t be contained by genre, race, or geography. Something called rock ’n’ roll.

1954 wasn’t just a turning point—it was a reckoning. It was the year music stopped whispering and started roaring. The year when rhythm and blues collided with country twang, gospel soul, and teenage rebellion to form something utterly new. Something that couldn’t be contained by genre, race, or geography. Something called rock ’n’ roll.

It was the year Alan Freed gave the movement a name. The year Bill Haley recorded the anthem that would shake the rafters. The year Elvis Presley stepped into Sun Studio and changed the trajectory of popular culture. It was the year DJs became cultural architects, and radio became the revolution’s loudest voice.

But more than anything, 1954 was the year music became a mirror. It reflected the tensions, the dreams, the defiance of a generation ready to break free. It gave voice to the voiceless, rhythm to the restless, and a beat to the brave. It didn’t ask for permission—it demanded to be heard.

At the USA Radio Museum, we honor 1954 not just as a historical milestone, but as a living legacy. Through rare broadcasts, curated playlists, and tribute features, we preserve the echoes of that seismic year. Because every time a guitar growls, every time a DJ drops the needle, every time a teenager turns up the volume—we’re still hearing 1954.

It was the year the silence broke. The year when radio, once a segregated soundscape, opened its arms to the pulse of Black America. 1954 was the year pop music shattered cultural barriers, as Black artists—once confined to the margins of ‘Race Music’—were finally heard on mainstream radio. And 1954 became the spark—igniting a sound that still burns in every beat we play today.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.