Introduction: A Name with a Clerical Voice That Stirred the Nation By the early 1930s, as America reeled from the Great Depression and searched for

Introduction: A Name with a Clerical Voice That Stirred the Nation

By the early 1930s, as America reeled from the Great Depression and searched for meaning in the static of uncertainty, one voice cut through the noise with startling clarity. It was not a president, nor a movie star, nor a business tycoon. It was a Catholic priest from Royal Oak, Michigan—Father Charles E. Coughlin—whose weekly radio sermons reached over 30 million listeners across the country. From the pulpit of the Cathedral of the Little Flower, Coughlin transformed himself into a national figure, blending religious conviction with political fire, and becoming one of the most influential—and controversial—voices in American broadcast history.

By the early 1930s, as America reeled from the Great Depression and searched for meaning in the static of uncertainty, one voice cut through the noise with startling clarity. It was not a president, nor a movie star, nor a business tycoon. It was a Catholic priest from Royal Oak, Michigan—Father Charles E. Coughlin—whose weekly radio sermons reached over 30 million listeners across the country. From the pulpit of the Cathedral of the Little Flower, Coughlin transformed himself into a national figure, blending religious conviction with political fire, and becoming one of the most influential—and controversial—voices in American broadcast history.

His rise marked the dawn of radio as a tool for mass persuasion. His fall revealed its capacity to spread division. For the USA Radio Museum, Coughlin’s legacy is not just a chapter in religious broadcasting—it is a cautionary tale about the power of the microphone, the reach of rhetoric, and the fragile line between faith and fanaticism. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

A Brief Biography: From Ontario Roots to Michigan’s Airwaves

Charles Edward Coughlin was born on October 25, 1891, in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, the only child of Irish Catholic parents. Raised in a modest home between a cathedral and a convent, he was steeped in religious tradition from an early age. He studied at St. Michael’s College in Toronto and was ordained in 1916. After teaching at Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, he crossed the border into Michigan and, in 1926, was assigned to establish a new parish in Royal Oak.

That parish would become the National Shrine of the Little Flower, a bold Art Deco basilica on Woodward Avenue that still stands today. It was here, amid rising anti-Catholic sentiment and Ku Klux Klan hostility, that Coughlin turned to radio—not just as a tool of outreach, but as a weapon of influence.

The Birth of a Broadcast Empire

Coughlin’s radio ministry began humbly in 1926, with local broadcasts on Detroit’s WJR. His early programs focused on biblical storytelling and moral guidance, including a segment called The Children’s Hour. But as the Great Depression deepened, his sermons took on a sharper edge. He began denouncing “godless communism,” defending labor rights, and advocating for sweeping monetary reform.

His program, The Golden Hour of the Little Flower, quickly gained traction. By 1930, CBS had picked up the show for national syndication, making Coughlin one of the first media figures to wield mass influence through radio. His broadcasts were delivered with theatrical flair—his voice rising and falling like a symphony of conviction—and his message resonated with millions of disaffected Americans.

Political Firebrand and Populist Crusader

Initially, Coughlin was a vocal supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, praising the president’s efforts to combat economic despair. But by 1934, he had turned sharply against Roosevelt, accusing him of being beholden to international bankers and betraying the working class.

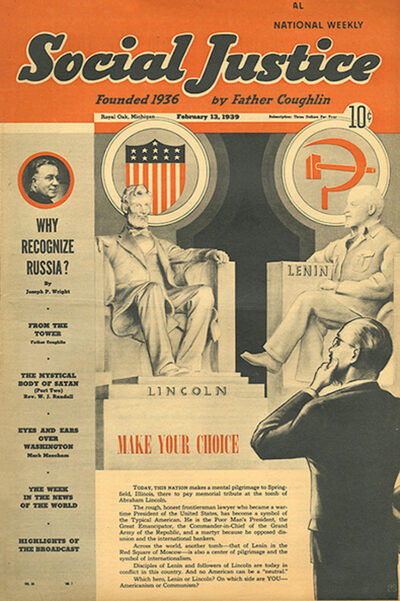

That same year, Coughlin founded the National Union for Social Justice, a populist movement that called for nationalizing major industries, abolishing the Federal Reserve, and protecting labor rights. His slogan—“Social Justice”—became a rallying cry, and his newspaper of the same name carried shrill attacks on Wall Street, communism, and what he called “Jewish influence” in American finance.

Coughlin’s broadcasts grew increasingly incendiary. He praised aspects of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and his coded antisemitism became more overt. By the late 1930s, his rhetoric had shifted from economic populism to ideological extremism, drawing condemnation from both political leaders and the Catholic Church.

WJR Detroit: The Tower Behind the Voice

Before Father Coughlin became “The Radio Priest,” he needed a platform—and WJR Detroit provided it. Known as “The Goodwill Station,” WJR was a rising force in Midwest broadcasting when Coughlin began airing his sermons in 1926. Though often misattributed to WWJ, it was WJR that carried his voice from Royal Oak to the nation.

Coughlin’s early broadcasts originated from a modest studio in the Shrine’s basement. WJR’s powerful signal helped him attract a vast audience, eventually drawing the attention of CBS, which syndicated his program nationally. In 1935, WJR officially left NBC and joined CBS, boosting its reach with a new 50,000-watt transmitter. This transition coincided with Coughlin’s move to self-syndication, relying on listener donations and the Radio League of the Little Flower to maintain airtime.

WJR’s role in Coughlin’s ascent underscores the station’s influence in shaping early American talk radio. Today, it remains a Detroit institution—but its association with Coughlin is a reminder of radio’s power, and its responsibility.

_____________________

A SIDEBAR | Poison Fruit: How Father Coughlin Articulated His Antisemitic Worldview Through the Airwaves

Father Charles E. Coughlin packed auditoriums and public arenas across the country, drawing millions.

As Father Charles E. Coughlin’s radio ministry evolved from spiritual outreach to political crusade, a troubling shift emerged in his rhetoric. By the late 1930s, his broadcasts and publications began to reflect a worldview steeped in antisemitic conspiracy theories and coded hostility toward Jewish communities.

Coughlin blamed Jewish financiers for the Great Depression, accused Jewish influence of corrupting American democracy, and echoed fascist propaganda in his denunciations of “international bankers.” His newspaper Social Justice reprinted excerpts from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious antisemitic forgery, and praised aspects of Nazi Germany’s economic policies. Though he often cloaked these views in religious or economic language, the underlying message was clear—and deeply harmful.

Jewish organizations, political leaders, and many within the Catholic Church condemned his broadcasts. By 1942, under pressure from the Roosevelt administration and the Archdiocese of Detroit, Social Justice was shut down, and Coughlin was ordered to cease all political activity.

This chapter of his legacy is painful but essential. It reminds us that mass media can amplify prejudice as easily as it can inspire hope—and that the power of the microphone must always be met with moral responsibility.

_____________________

Watched from the Shadows: Father Coughlin and the FBI

Though Father Charles E. Coughlin railed against Communism in his sermons and publications, his own activities drew the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI—not as a suspected Communist agent, but as a potential fascist sympathizer and seditionist.

From 1936 through the early 1940s, federal agents monitored Coughlin’s broadcasts, writings, and political organizing. His newspaper Social Justice—which reprinted antisemitic texts like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and praised aspects of Nazi Germany’s policies—raised alarms within the Roosevelt administration. His formation of the National Union of Social Justice, a populist political movement, further intensified scrutiny.

Coughlin’s rhetoric was deeply anti-Communist, often framing Marxism as a threat to Christian civilization. Yet his sympathy for fascist regimes, hostility toward Jewish communities, and denunciations of American democracy placed him in direct conflict with wartime efforts to suppress extremist propaganda.

Coughlin’s rhetoric was deeply anti-Communist, often framing Marxism as a threat to Christian civilization. Yet his sympathy for fascist regimes, hostility toward Jewish communities, and denunciations of American democracy placed him in direct conflict with wartime efforts to suppress extremist propaganda.

The FBI’s files, now archived at the Walter P. Reuther Library in Detroit, reveal a man whose voice reached millions—and whose message was considered dangerous enough to warrant federal surveillance. By 1942, under pressure from both the government and the Catholic Church, Coughlin was silenced. His newspaper was shut down, and his political activity ceased.

This chapter of Coughlin’s legacy reminds us that dissent, when amplified through mass media, can walk a fine line between critique and incitement. And that even the most powerful voices on the airwaves are never beyond the reach of accountability.

Controversy and Collapse

As World War II loomed, Coughlin’s broadcasts became untenable. In 1939, the National Association of Broadcasters forced the cancellation of The Golden Hour. In 1942, under pressure from the Roosevelt administration and the Archdiocese of Detroit, his newspaper Social Justice was shut down and barred from mail distribution under the Espionage Act.

Coughlin retreated from public life, continuing to serve quietly as a parish priest at the Shrine of the Little Flower until his retirement in 1966. He died in 1979 at age 88, buried in Southfield, Michigan.

The Shrine and the Symbolism

The National Shrine of the Little Flower Basilica stands as one of Michigan’s most iconic religious and architectural landmarks. Located on 12 Mile Road in Royal Oak, its bold Art Deco design, soaring Charity Crucifixion Tower, and intricate stone reliefs reflect both the grandeur and gravity of its origins. Built in 1931 during the depths of the Great Depression, the Shrine was more than a parish—it was a statement of Catholic resilience in the face of rising anti-Catholic sentiment, including threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

The National Shrine of the Little Flower Basilica stands as one of Michigan’s most iconic religious and architectural landmarks. Located on 12 Mile Road in Royal Oak, its bold Art Deco design, soaring Charity Crucifixion Tower, and intricate stone reliefs reflect both the grandeur and gravity of its origins. Built in 1931 during the depths of the Great Depression, the Shrine was more than a parish—it was a statement of Catholic resilience in the face of rising anti-Catholic sentiment, including threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

Father Charles E. Coughlin, the parish’s founding priest, envisioned the Shrine as both a house of worship and a fortress of faith. Its tower, emblazoned with a massive crucifix visible for miles, was meant to proclaim spiritual strength and defiance. Inside, Coughlin preached to packed pews while his voice echoed across the country via WJR’s powerful signal. Outside, crowds gathered—some in reverence, others in protest—drawn by the magnetism of a man who blurred the line between priest and political provocateur.

But the Shrine’s story didn’t end with Coughlin. In the decades that followed, the parish evolved, shedding the shadow of its controversial founder while embracing the gentle spirituality of its patroness, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, known as “The Little Flower.” Her philosophy of doing “small things with great love” became the guiding ethos of the community.

A Living Parish Today

Today, the Shrine remains an active and vibrant parish, serving the Royal Oak community and beyond. It was elevated to the status of a minor basilica by the Vatican in 1998, recognizing its historical and spiritual significance. The church is home to Shrine Catholic Schools, a thriving educational campus, and hosts regular Masses, confessions, retreats, and community events.

In October 2025, the Shrine welcomed the relics of St. Thérèse for the first time in 26 years, drawing thousands of pilgrims from across the region. The basilica was adorned with roses, and the sanctuary filled with prayer, music, and reverence. Parishioners, students, and visitors alike gathered to venerate the saint whose “Little Way” continues to inspire acts of kindness and devotion.

The Shrine’s centennial celebration is underway, marking 100 years of ministry and memory. It remains a place where history lives, faith flourishes, and the echoes of the past are met with the hope of renewal.

Reflection: Radio’s Power and Peril

Father Charles E. Coughlin’s story is not just about one man—it’s about the medium itself. His rise marked the dawn of radio as a tool for mass persuasion, capable of shaping public opinion and mobilizing movements. His fall revealed the dangers of unchecked rhetoric, especially when cloaked in religious authority.

For the USA Radio Museum, Coughlin’s legacy invites us to examine the ethics of broadcasting, the responsibilities of public voices, and the enduring tension between faith, politics, and media. His broadcasts were among the first to prove that radio could do more than entertain—it could inspire, educate, inflame, and divide.

The Silencing of the Radio Priest

By the early 1940s, Father Charles E. Coughlin had worn out his welcome on the national stage. His increasingly inflammatory broadcasts—laden with antisemitic rhetoric and conspiracy theories—alienated major radio networks. Appalled by his diatribes, CBS and NBC dropped him, severing ties with one of the most powerful voices in American broadcasting.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the United States’ entry into World War II, Coughlin’s staunch isolationism and vocal opposition to the war effort became politically toxic. In response, the federal government invoked the Espionage Act of 1917 to revoke the second-class mailing permit for Social Justice, effectively crippling his ability to distribute his newspaper nationwide.

The final blow came on May 1, 1942, when Coughlin’s superiors in the Catholic Church ordered him to cease all political broadcasting. He complied, later stating, “Disobedience is a great sin.” Though he believed he could have rallied public support to continue, he admitted, “I didn’t have the heart left, for my church had spoken.”

He returned to his parish in Royal Oak—by then nicknamed by critics as “the Shrine of the Little Führer”—and remained its pastor until his retirement in 1966. When he died in 1979 at age 88, the world responded with quiet acknowledgment. Eleven years earlier, in a rare interview, he stood by the positions he had taken during his heyday, never recanting the views that had once electrified—and divided—a nation.

The Quiet Exit: Reactions to Father Coughlin’s Retirement and Death

After decades of controversy, national broadcasts, and political agitation, Father Charles E. Coughlin retired quietly fifty-nine years ago, from his role as pastor of the National Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan. By then, he had long been silenced by the Catholic Church and removed from the public spotlight. His retirement was not widely covered in national media, and there was no major public ceremony or statement—a stark contrast to the millions who once tuned in to hear his voice.

When Coughlin passed away in 1979 at age 88, the world reacted with muted acknowledgment. His death was noted in regional obituaries and Catholic circles, but there was no national outpouring, no major retrospectives, and no official statements from the Church or government. The silence spoke volumes: once one of the most powerful voices on American radio, Coughlin had become a cautionary tale of influence lost to extremism.

Historians and journalists who did reflect on his passing often framed him as a demagogue, a pioneer of mass media populism, and a figure whose antisemitic and fascist sympathies had permanently tarnished his legacy. The New York Times obituary described him as “a once-powerful radio priest whose voice had long since faded from the airwaves.”

Yet in Royal Oak, the Shrine remained open. Parishioners continued to worship, and the community moved forward—choosing to honor the spiritual mission of the church rather than the political legacy of its founder.

Echoes of Influence: The Father Coughlin Broadcast Collection (1937–1940)

The USA Radio Museum proudly preserves a rare and comprehensive archive of 64 original broadcasts by Father Charles E. Coughlin, spanning the pivotal years of 1937 to 1940. These recordings capture the final phase of Coughlin’s radio career—when his sermons, once rooted in spiritual guidance, had evolved into fiery political commentary that stirred both devotion and dissent across the nation.

The USA Radio Museum proudly preserves a rare and comprehensive archive of 64 original broadcasts by Father Charles E. Coughlin, spanning the pivotal years of 1937 to 1940. These recordings capture the final phase of Coughlin’s radio career—when his sermons, once rooted in spiritual guidance, had evolved into fiery political commentary that stirred both devotion and dissent across the nation.

Broadcast from the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan, and carried nationally via WJR and independent syndication, these programs reflect the full spectrum of Coughlin’s rhetoric: from impassioned theological reflections to provocative critiques of democracy, communism, and American leadership. They are sonic artifacts of a turbulent era—when radio was not just a medium, but a movement.

Featured Broadcasts

For this presentation, the museum has selected three historic broadcasts from the collection to showcase:

1. “Communism Vs. Christianity” — February 14, 1937

In this early broadcast, Coughlin draws stark contrasts between Christian doctrine and communist ideology, framing the struggle as a moral and spiritual battle for the soul of America.

_____________________

Father Charles E. Coughlin | CBS WJR (Detroit) | February 14, 1937

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

2. “So This Is Democracy” — April 30, 1939

Delivered amid rising global tensions, this sermon questions the integrity of democratic institutions and reflects Coughlin’s growing disillusionment with American political leadership.

_____________________

Father Charles E. Coughlin | CBS WJR (Detroit) | April 30, 1939

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

3. “Communism Accepts Religion” — March 3, 1940

One of his final major broadcasts, this program explores shifting ideological landscapes and attempts to reconcile religious belief with political systems once deemed incompatible.

Each selection is presented with restored audio, contextual commentary, to help visitors experience the broadcasts as they were heard by millions—raw, resonant, and deeply polarizing.

_____________________

Father Charles E. Coughlin | CBS WJR (Detroit) | March 3, 1940

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

Epilogue: Lessons in Legacy

Today, as we navigate a new era of digital media and polarized discourse, the story of Father Coughlin remains strikingly relevant. He was a pioneer of talk radio, a master of emotional appeal, and a cautionary figure whose influence outpaced his accountability.

In honoring radio history, we must also confront its complexities. Coughlin’s voice may have faded, but the echoes remain—in every broadcast that seeks to sway hearts and minds, in every microphone that carries more than just sound.

_____________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.