From Music into Mourning, the Voices of ABC News Carried America Through its Darkest Hour On November 22, 1963, at 12:36 p.m. Central Standard Time

From Music into Mourning, the Voices of ABC News Carried America Through its Darkest Hour

On November 22, 1963, at 12:36 p.m. Central Standard Time, a voice broke across the ABC Radio Network that would forever be etched into the nation’s memory. Don Gardiner, steady and authoritative, the veteran and longtime ABC News anchor, promptly interrupted regular programming with words that carried shock and sorrow: President John F. Kennedy had been shot in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas.

On November 22, 1963, at 12:36 p.m. Central Standard Time, a voice broke across the ABC Radio Network that would forever be etched into the nation’s memory. Don Gardiner, steady and authoritative, the veteran and longtime ABC News anchor, promptly interrupted regular programming with words that carried shock and sorrow: President John F. Kennedy had been shot in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas.

It was the first nationwide bulletin of the tragedy, preceding television and rival networks by crucial minutes. In that instant, millions of Americans—at work, in cars, at home—were bound together by radio’s immediacy. The medium that had carried them through wars, elections, and everyday life now delivered the unthinkable.

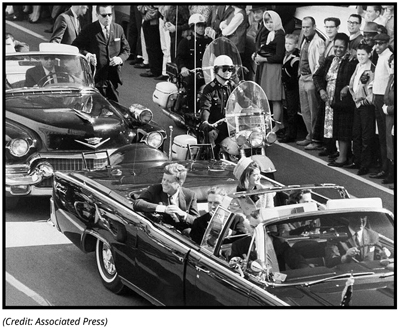

Jubilant, receptive crowds line the streets to greet President Kennedy and the First Lady as they traveled through Dallas. Main St. near N. Ervay. The time is 12:25 p.m., Friday, November 22. (Photo: Bob Jackson, Dallas Morning News)

What we will be presenting in this historical feature is the first five hours (from seventy-two hours of reporting in the next four days) of ABC radio coverage when the news first broke, a tapestry of voices struggling to keep pace with history as it unfolded. From Gardiner’s initial announcement to the confirmation of Kennedy’s death, from eyewitness reports to the solemn transfer of power to Lyndon B. Johnson, ABC Radio became the nation’s lifeline. The cadence of the broadcasts—hesitant pauses, urgent updates, moments of silence—captured the raw humanity of a country in shock.

Sixty-two years later, the USA Radio Museum reflects on this day not only as a turning point in American history, but as a defining moment in broadcast journalism. By preserving and presenting the original ABC Radio coverage, we invite listeners to experience the day as it was lived: minute by minute, voice by voice, bulletin by bulletin.

This is not simply an archive—it is a living memory. It is the sound of a nation learning, grieving, and enduring together. As we reflect on November 22, 1963, we remember the power of radio to connect hearts in the darkest of hours, and the enduring responsibility of voices like Don Gardiner’s to deliver urgency in tone in the most tragic moment this country endured in the 1960s —when it happened—as it happened. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Early Morning, Friday, November 22, 1963

“November the 22nd began without a hint that it would be remembered.

The country awoke without knowing its President was to sleep.” — Gregory Peck, ‘John F. Kennedy: Years of Lightning, Day of Drums’ (1965)

The marquee at Hotel Texas welcomes President Kennedy’s arrival there in Fort Worth. Thursday night, November 21, 1963.

The morning of Friday, November 22, 1963 began as auspiciously as any day during President Kennedy’s first term in office. Having arrived in Texas on Thursday, November 21, for stops in San Antonio and Houston, the Presidential entourage flew to Fort Worth late that evening. At 11:50 p.m. CST, President Kennedy and the First Lady checked into Suite 850 at the Hotel Texas in downtown Fort Worth.

Friday’s itinerary was ambitious. Kennedy was scheduled to deliver two public speeches in Fort Worth—one outside the hotel’s parking lot, and another at a Chamber of Commerce breakfast inside the Grand Ballroom. From there, the President and Mrs. Kennedy would take a short 13‑minute flight from Carswell Air Force Base to Love Field in Dallas. A motorcade through the city was planned, culminating in an afternoon luncheon and a major speech at the Trade Mart. Later that evening, Kennedy was to fly to Austin for a Democratic fundraising dinner at Vice President Lyndon Johnson’s ranch.

The Hotel Texas marquee welcomed the President’s arrival on November 21, a symbol of civic pride and anticipation.

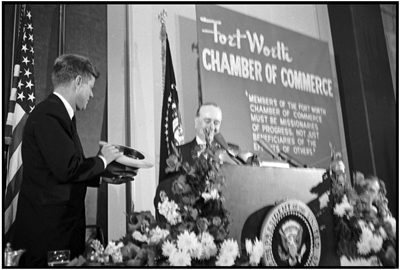

President Kennedy is presented with a Washer Bros. Stetson Road Hat “for some protection against the rain” by Raymond Buck, president of the Ft. Worth Chamber of Commerce, before addressing a crowd of 2,000 guests gathered for breakfast in the Grand Ballroom at the Hotel Texas. (Photo: Ft. Worth-Star Telegram)

Meanwhile, the day’s national headlines reflected a world in flux. The “Soviet staff” was abruptly ousted in the Congo. Debris from a crashed U‑2 plane was found in the Gulf north of Havana. South Africa rejected UN compliance to end racial bias. Attorney General Robert Kennedy announced he would not direct his brother’s 1964 campaign. Robert Stroud, the infamous “Birdman of Alcatraz,” had died. In Dallas, Richard Nixon told reporters that Kennedy would drop Lyndon Johnson from the ticket in 1964. And in Vietnam, The Detroit Free Press reported—via United Press International—that 1,300 U.S. military personnel would be withdrawn within two months.

According to the Detroit Free Press, found printed in their early-morning edition on November 22, 1963, the newspaper’s own headlines painted a picture of local life on that Friday morning. The state’s jobless rate dipped to 3.9 percent, a seven‑year low, thanks to the booming auto industry. Investigations revealed Teamsters pension funds had been funneled into Las Vegas gambling enterprises. The Detroit Stock Exchange reported a strong October markup. In sports, the Red Wings stood at 6‑8 in the NHL standings, while the Tigers traded Rocky Colavito to Kansas City. The Fox Theatre marquee billed The Man With the X‑Ray Eyes, and the Olympia was hosting the Ice Follies of 1964. Michigan State prepared to face Illinois in collegiate football. And Detroiters were reminded by retail ads that only 33 shopping days remained until Christmas.

The weather forecast for Southeast Michigan promised mild temperatures—gray and overcast, a possibility for rain, highs in the 60s, lows in the 40s.

The weather forecast for Southeast Michigan promised mild temperatures—gray and overcast, a possibility for rain, highs in the 60s, lows in the 40s.

In Fort Worth and Dallas, however, the biggest story was Kennedy’s whirlwind two‑day trip to Texas. At 7:00 a.m. CST, WBAP 570’s Norwood McClendon delivered local morning news with Morning Edition. From New York, ABC’s Don Gardiner anchored News Around the World, a segment that also aired at 8:15 a.m. EST on Detroit’s ABC affiliate WXYZ Radio 1270. These broadcasts carried the ordinary rhythms of a Friday morning—local news, weather, farm reports, commerce—unaware that within hours, the airwaves would carry the most shocking bulletin in American memory and 20th. Century history.

WBAP-AM 570 | Dallas Ft. Worth (ABC Radio) | Morning Edition (Norwood McClendon) | News Around the World (Don Gardiner) | Early Friday Morning, November 22, 1963

Audio Digitally Enhanced by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

Archival Note: WBAP ABC Radio Morning Audio

The USA Radio Museum preserves the original WBAP/ABC Radio Morning Edition audio from the early hours of November 22, 1963. This recording captures Don Gardiner’s ‘News Around the World’ segment as it aired while President Kennedy was still alive at the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth. Featuring this audio allows listeners to experience the contrast between the routine cadence of morning news and the seismic break‑in Gardiner would deliver hours later—at 12:36 p.m. CST—announcing shots fired at the President’s motorcade in Dallas.

_____________________

The First Bulletin

At 12:36 p.m. CST, Don Gardiner interrupted ABC Radio programming with words that would forever be remembered: “We interrupt this program with a special bulletin from ABC Radio . . . .” His voice was calm, authoritative, but urgent. This was the first nationwide bulletin—preceding television and rival networks by crucial minutes.

The First Break‑In: ABC Radio, 12:36 p.m. CST

“We interrupt this program to bring you a special bulletin from ABC Radio— (five‑second pause)

Here is a special bulletin from Dallas, Texas. Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade today in downtown Dallas, Texas. This is ABC Radio. A repeat. Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade today. The President now making a two‑day speaking tour of Texas. We’re going to stand by for more details on the incident in Dallas. Stay tuned to your ABC station for further details. Now we return you to your regular program…”

(34‑second pause, followed by a four‑second beeping tone heard repeated three times, then in continuation another special bulletin followed and was reported by Don Gardiner.)

Interpretive Note

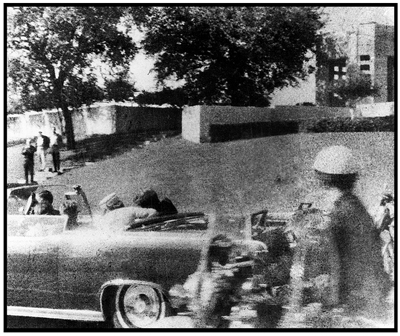

The Presidential limousine with the mortally wounded President is photo captured on the Stemmons Freeway speeding towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. It is 12:33 p.m. Dallas time.

This was the moment when ordinary programming ended and history began. The pauses were deliberate, giving listeners time to absorb the words. The line stood out—“Three shots were fired . . .”—underscored the gravity of the report while avoiding speculation. The technical beeps and tones signaled the network’s transition, preparing affiliates and listeners for further bulletins.

Within minutes, Don Gardiner’s voice would return with additional details, guiding the nation through the confusion and disbelief. For millions of Americans, this was the first sound of tragedy—the moment they learned their President had been struck down in Dallas.

In Detroit, Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and in Washington, all ABC affiliates, the shocking news first broke. Immediately thereafter, within two-minutes, the news was picked up by NBC, CBS, and Mutual, and radios suddenly flashed the same words. The immediacy of Gardiner’s announcement meant that millions learned of the shooting simultaneously, bound together by sound. Listeners froze.

Behind the microphone, Gardiner was relaying wire service reports rushing into ABC’s newsroom. The decision to break programming was instantaneous. Radio’s agility allowed Gardiner’s voice to carry the unthinkable before television could mobilize what was being reported.

Behind the microphone, Gardiner was relaying wire service reports rushing into ABC’s newsroom. The decision to break programming was instantaneous. Radio’s agility allowed Gardiner’s voice to carry the unthinkable before television could mobilize what was being reported.

For many, this was the moment when ordinary time ended. Offices fell silent, cars pulled over, families gathered around radios. The cadence of Gardiner’s voice carried the shock into every corner of the country, from coast-to-coast across the ABC Radio Networks’ affiliated stations.

The Second Break‑In: ABC Radio, 12:37 p.m. CST

“We interrupt this program for another bulletin from ABC Radio— (twenty-four second pause)

The Associated Press wires breaks with a bulletin. President Kennedy has been shot. 12:40 p.m., CST; November 22 (Jim Feliciano Collection)

Here is a bulletin from ABC Radio. More on the shots fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade today in downtown Dallas. No casualties have been reported in the first bulletin. However, there is a later bulletin that says there is perhaps a serious injury. The incident took place near the county sheriff’s office on Main Street just east of an underpass leading toward the Trade Mart where the president was to make an address . . . .”

Interpretive Note

This second bulletin, delivered less than two minute after the first, carried the story from rumor into vivid detail. Gardiner’s words painted the scene: Kennedy slumping forward, Connally collapsing, Jackie Kennedy’s anguished cry. Yet even here, the restraint remained—having cautiously repeated twice— “It is not known whether either was killed.”

Listeners across America were now gripped by the immediacy of radio. The pauses, the repetition, the careful balance between eyewitness detail and official uncertainty created a rhythm of shock and disbelief. For millions, this was the moment when the assassination became real, though the full weight of tragedy had not yet been confirmed.

The Third Break-In: ABC Radio, 12:38 p.m. CST

“Here is a special bulletin from ABC Radio—

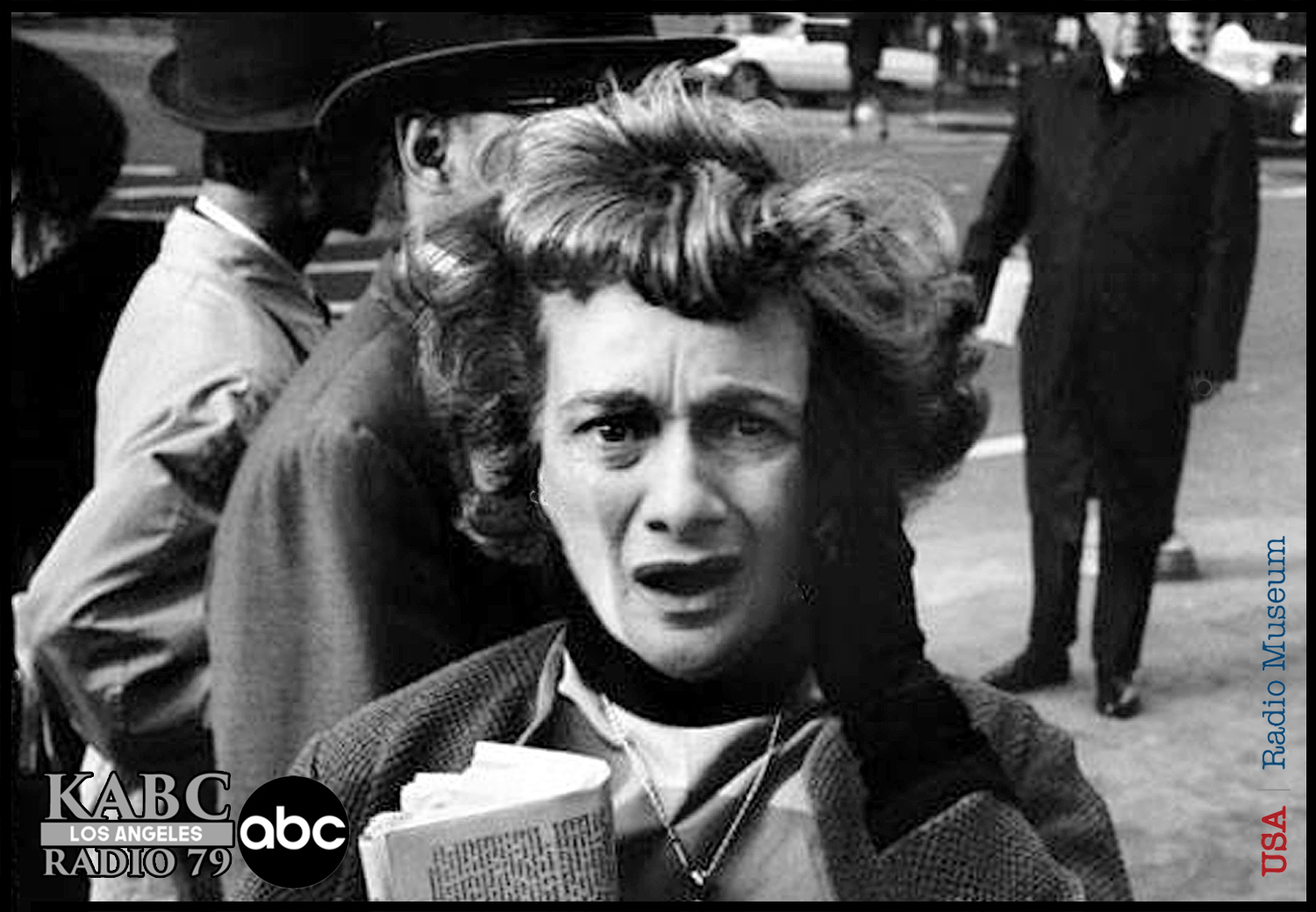

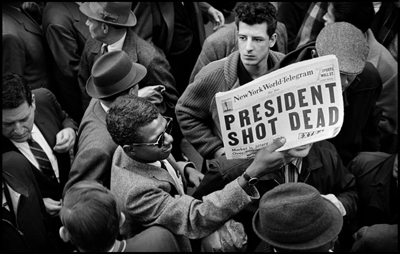

Stunned New Yorkers listening to an open car’s radio for the latest news surrounding President Kennedy’s shooting in Dallas. W. 46th Ave., November 22, 1963.

President Kennedy and Governor Connally of Texas have been cut down by assassin’s bullets in downtown Dallas. They were riding in an open automobile when the shots were fired. The President slumped over in the back seat of the car, face down. Connally fell to the floor of the vehicle. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and cried, ‘Oh no!’ The motorcade sped to Parkland Hospital, where both men were given emergency treatment. It is NOT known whether either was killed. It is NOT known whether either was killed.”

Interpretive Note

This third bulletin repeated the vivid eyewitness detail from the second, but added a deliberate emphasis on uncertainty. Gardiner’s repetition—“It is NOT known whether either was killed. It is NOT known whether either was killed”—was not accidental. It reflected both the wire service caution and the broadcaster’s responsibility to avoid speculation.

For listeners, the repetition carried a haunting rhythm. It underscored the gravity of the situation while reminding the nation that confirmation had not yet come. In those moments, radio was both a lifeline and a restraint—providing detail, but holding back from declaring the worst until official word arrived.

This bulletin illustrates the tension of live reporting: the balance between eyewitness description and the need for accuracy. It also shows how Gardiner’s voice became the steady thread guiding millions through confusion, disbelief, and fear.

The Fourth Bulletin: ABC Radio, 1:42 p.m. CST (2:42 p.m. EST)

“The President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, is dead.”

(five‑second pause)

“Let us pray.”

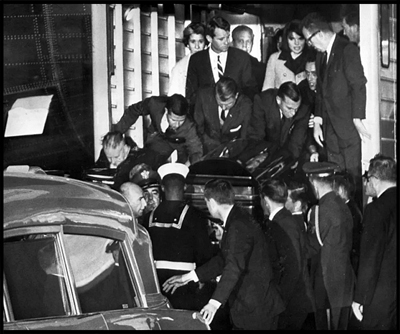

The O’Neill Funeral hearse transporting the slain President’s body from Parkland Hospital to Love Field Airport for the return trip back to Washington. 2:15 p.m., CST. (Credit: Dallas Times Herald)

Immediately following Gardiner’s solemn words, the ABC Radio Network played dirge music—somber and reverent—for approximately 23 seconds. This brief interlude transformed the airwaves into a national requiem, allowing listeners to absorb the enormity of the moment.

When the music faded, Gardiner’s voice returned, steady but weighted with sorrow:

“The ABC Radio Network has added its voice with the report that President Kennedy is dead. The President of the United States is dead, of an assassin’s bullet, in Dallas, Texas.”

Interpretive Note

This was the moment when disbelief gave way to certainty. Gardiner’s pause after the words “is dead” carried the weight of national grief. His invocation—“Let us pray”—was both a broadcaster’s instinct and a communal call to mourning.

The dirge music, brief yet profound, marked a ritual of transition: from shock into sorrow, from uncertainty into collective mourning. For millions of listeners, this was the instant the tragedy crystallized. Unlike television, which offered images, radio conveyed raw emotion through tone, silence, and sound.

Gardiner’s voice became the nation’s guide through the darkest of hours. His cadence, the pauses, the repetitions, and the solemnity of the announcement are preserved today as living echoes of November 22, 1963.

KABC-AM 790 (Los Angeles) | ABC Radio Network (NEWS FLASH 10:36 A.M. P.T.) | November 22, 1963 [A]

Audio Digitally Enhanced by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

Sidebar: “Hooray for Hollywood” — From Music into Immediate Shock, the Voices of ABC Carried America Through its Darkest Hour

At 10:36 a.m. Pacific Time (12:36 p.m. Central Time in Dallas), ABC Radio newscaster Don Gardiner broke into national programming with the first bulletin announcing shots fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade.

At 10:36 a.m. Pacific Time (12:36 p.m. Central Time in Dallas), ABC Radio newscaster Don Gardiner broke into national programming with the first bulletin announcing shots fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade.

The program airing on KABC in Los Angeles at that moment was the ABC network’s ‘Music in the Afternoon’, hosted by Dirk Fredericks and Joel Crager. A recording of the national ABC network coverage confirms that Doris Day’s Hooray for Hollywood was playing when Gardiner interrupted.

Local affiliates often had the option to air their own content or the national feed, but Gardiner’s bulletin was a national interruption—cutting across whatever was on the air to deliver the shocking news.

The USA Radio Museum’s archived recording, captured from over 5 hours of KABC‑AM in Los Angeles (and after the first flash bulletin first broke from ABC in New York, the network took control of the news coming from Dallas beginning at 12:36 p.m., CST. This would culminate into 72 hours of continuous ABC Radio coverage across the network’s affiliates that weekend), preserves this exact moment. Visitors can hear “Hooray for Hollywood” playing just before Gardiner’s voice breaks in with the words that changed history.

This juxtaposition—the cheerful strains of a Hollywood anthem abruptly silenced by the announcement of tragedy—underscores the shock of November 22, 1963. It is a reminder of how an ordinary day ended in an instant, and how radio stunned the nation from music to immediate shock, disbelief, and to collective mourning as the news broke repeatedly throughout that day.

_____________________

Confusion and Conflicting Reports

The next half hour was filled with uncertainty. Gardiner repeated what was known: “It is NOT known whether either was killed. It is NOT known whether either was killed.” His deliberate repetition underscored the gravity of the situation while avoiding speculation.

Reporters in Dallas—Bob Clark among them—described Kennedy slumping forward, Jacqueline Kennedy crying out, Connally bleeding beside him. United Press International relayed statements from a Catholic priest at Parkland Hospital suggesting the President was dead. Yet ABC Radio held back, refusing to confirm without official word from Dallas or Washington.

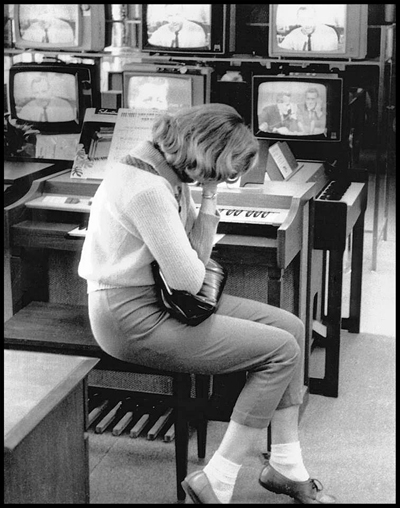

Listeners clung to every word. Offices fell silent, cars pulled over, families gathered around radios. The pauses, the repetitions, the careful restraint—all became part of the emotional texture of the day.

The tension was palpable. Rumors spread quickly, but Gardiner’s voice remained steady, repeating only what was confirmed. This restraint gave ABC Radio credibility, even as listeners longed for clarity.

Climax: The 1:42 Bulletin

At approximately 1:42 p.m. CST (2:42 p.m. EST), Gardiner broke in with the definitive UPI bulletin: “The President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, is dead.” He paused for five long seconds, the silence itself a marker of grief, before adding in solemnity: “Let us pray.”

Immediately, the ABC Radio Network played dirge music—somber and reverent—for approximately 23 seconds. This brief interlude transformed the airwaves into a national requiem, allowing listeners to absorb the enormity of the moment. Then, the network returned live to the microphone, continuing its duty to report the unfolding events from Dallas and Washington.

Gardiner’s next words sealed the moment: “The ABC Radio Network has added its voice with the report that President Kennedy is dead. The President of the United States is dead, of an assassin’s bullet, in Dallas, Texas.”

For millions of listeners, this was the instant the tragedy crystallized. The wavering voice, the pause, the invocation to prayer, and the short but powerful dirge combined to create an auditory tableau of mourning. Unlike television, which offered images, radio offered raw emotion through tone, silence, and sound.

The Immediate Aftermath

When the music was abruptly cut, Gardiner’s voice returned, steady but weighted with sorrow. He began relaying further wire service updates: confirmation from Parkland Hospital, eyewitness accounts of what occurred in Dealey Plaza, and the first mentions of Vice President Lyndon Johnson sustaining possible injuries during the shooting.

Listeners heard the cadence of a newsroom struggling to balance reverence with responsibility. Gardiner repeated the words “The President is dead” with careful solemnity, ensuring clarity across the nation. Other correspondents joined in, describing the atmosphere in Dallas: the chaos outside Parkland, the stunned crowds along the motorcade route, the disbelief etched on faces stunned with utter shock.

In Washington, ABC affiliates reported the sudden paralysis of government offices, the gathering of staff at the White House, and the first reports for preparation for Johnson’s swearing‑in as President (Johnson was sworn-in on Air Force One at Love Field at 2:38 CST before taking off to Washington at 2:47 p.m., CST). The network’s coverage became a bridge between two cities—Dallas, where “the incident” occurred, and Washington, where the weight of succession now fell.

For listeners, the transition from dirge to continuous live-feed reporting was itself symbolic: grief had to give way to the grim work of understanding, documenting, and carrying the nation forward. The sound of Gardiner’s voice, returning after those 23 seconds of music, was the sound of history resuming its course.

The Hours That Followed

By mid‑afternoon, reports began to circulate about Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. He had been three cars behind Kennedy in the Dallas motorcade and was quickly taken under Secret Service protection. At Parkland Hospital, Johnson waited in a secure room when doctors later confirmed Kennedy’s death.

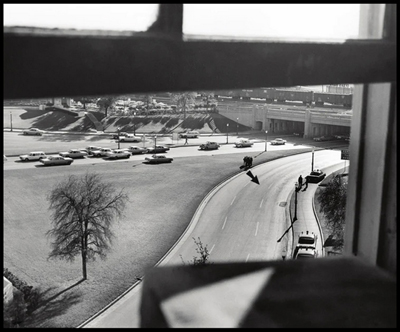

The alleged sniper’s view of Elm Street from the 6th. floor of the Texas School Book Depository building, Dallas. Late Friday afternoon. (Photo: Dallas Times Herald)

At 2:38 p.m. CST, aboard Air Force One at Love Field, Johnson took the oath of office administered by Judge Sarah T. Hughes. ABC correspondents described the scene in hushed tones: Johnson’s hand on a Catholic missal, Jacqueline Kennedy standing beside him in her blood‑stained pink suit. The swearing‑in was not broadcast live, but radio carried the news within minutes, recorded and preserved on a portable dictabelt machine, emphasizing the continuity of government even in the midst of grief.

In Washington, ABC affiliates reported stunned silence across government offices. Staff gathered in corridors, listening to radios perched on desks. Churches opened their doors, and bells tolled in mourning. The White House press room fell into a hush as word spread that the President’s body would soon be flown back from Dallas.

By early evening, ABC Radio turned its attention to Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington. At 6:05 p.m. EST, Air Force One landed with Kennedy’s casket aboard. Radio listeners heard descriptions of the scene: the airbase’s towering lights piercing the darkness, the removal of the casket, Jacqueline Kennedy still wearing her blood-soaked pink suit, her face pale but resolute.

Correspondents described the hush among the gathered officials, the solemnity of the military honor guard, and the quiet dignity of Mrs. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy as he accompanied his brother’s body for the trip to Bethesda Naval Hospital for autopsy. For listeners, these reports carried the weight of ritual—the transition from the chaos of Dallas to the solemn mourning of Washington, and the entire country.

KABC-AM 790 (Los Angeles) | ABC Radio Network (CONTINUOUS COVERAGE) | November 22, 1963 [B]

Audio Digitally Enhanced by USA Radio Museum

Historical Resonance

The Kennedy assassination is remembered through images—the motorcade in Dealey Plaza, Walter Cronkite removing his glasses—but it is also remembered through sound. Gardiner’s voice, Bob Clark’s eyewitness reports, the pauses and repetitions, the wavering moment when “He is dead” was read aloud—all became part of the nation’s auditory memory.

Radio’s immediacy gave it unique power. It was the first to carry the news nationwide, binding listeners together in shock. Its intimacy made the experience deeply personal, as if the voice were speaking directly into each home and car. And its continuity guided the nation through the unfolding hours, from the first bulletin to the solemn arrival of Kennedy’s casket in Washington.

Radio’s immediacy gave it unique power. It was the first to carry the news nationwide, binding listeners together in shock. Its intimacy made the experience deeply personal, as if the voice were speaking directly into each home and car. And its continuity guided the nation through the unfolding hours, from the first bulletin to the solemn arrival of Kennedy’s casket in Washington.

The cultural aftermath was profound. For many, the sound of Gardiner’s bulletin became inseparable from the memory of Kennedy’s death. Families recalled where they were when they heard the words. Offices remembered the silence that fell after the announcement. Churches remembered the bells that tolled in response. The cadence of radio broadcasts became part of the nation’s identity, shaping how grief was experienced and remembered.

Television would later provide the images—assassination eye witnesses, the swearing‑in of Lyndon Johnson, the funeral procession. But radio provided the immediacy, the raw emotion, the first communal experience of loss. It was radio that carried the nation from shock into mourning, guiding listeners minute by minute through the darkest of hours.

Archival and Preservation

The five hours of ABC Radio coverage from November 22, 1963 are more than recordings—they are living documents of national grief. Preserved in the USA Radio Museum archives, they capture the progression of that day in real time: from Gardiner’s first stunned bulletin at 12:36 p.m. CST, through the stunning confirmation at 1:42 p.m. CST, to the solemn arrival of Kennedy’s casket at Andrews Air Force Base, later that evening.

The casket containing the body of John F. Kennedy is moved to a Navy ambulance from the Presidential plane at Andrews Base. Mrs. Kennedy is behind it on elevator. Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy is beside her. (Credit: Boston Herald)

These broadcasts are not polished retrospectives; they are raw, immediate, and human. They contain the hesitations of reporters, the repetitions of uncertain facts, the pauses heavy with disbelief, and the brief dirge music that marked the moment of confirmation. They allow us to hear history as it was lived—not summarized, not edited, but unfolding minute by minute.

For historians, journalists, and citizens alike, the preservation of these recordings is vital. They remind us that radio was the nation’s first responder, carrying the shock of Kennedy’s assassination into homes, offices, and cars across America. They show how voices—Gardiner’s calm authority, Bob Clark’s eyewitness urgency, the solemn cadence of wire service bulletins—shaped collective memory.

The USA Radio Museum’s stewardship ensures that future generations can experience this immediacy. To hear Gardiner’s emotional call to the nation in that brief moment, with his three-worded reverent call “Let us all pray” is to feel the weight of national grief. To hear the 23 seconds of dirge music is to understand how sound itself became immediate. To hear the repetition of “The President is dead” is to grasp how language carried the unbearable and shocking reality to a stunned nation.

Sound archives are cultural memory. They preserve not only information but emotion—the tone, cadence, and silence that defined how Americans experienced tragedy. In an age dominated by images, these recordings remind us that sound has its own power to connect, console, and endure.

Radio was the first medium to carry the tragedy nationwide, its immediacy and intimacy shaping how America experienced that dark day.

The USA Radio Museum relives today the importance in having preserved this ABC coverage, living echoes of shock, sorrow, and resilience. These voices remind us that history is not only seen, but heard—and that sound itself has captured the weight of a nation’s travail and mourning we universally experienced that day in 1963.

Today, in remembering that day in November, we also reflect on how radio was able to shape national tragedy in real time—as it happened—and the importance of preserving voices that carried the nation through its darkest hours. These recordings are not relics; they are echoes of the past—still resonant, still alive, still capable of moving hearts, stirring our emotions and our memories even still to this day, 62 years later.

_________________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_________________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.