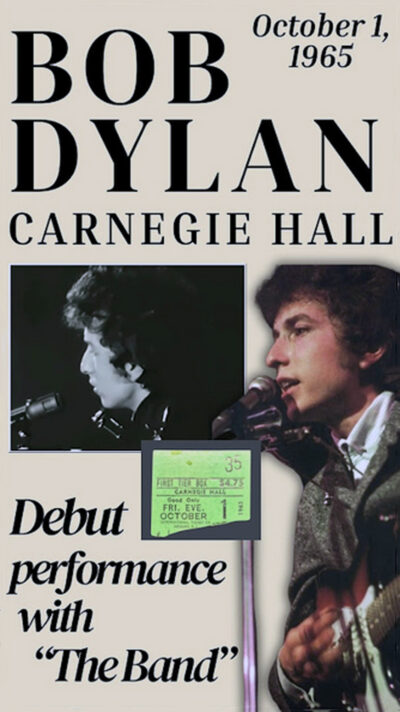

This Day in Pop Music History: October 1, 1965 Bob Dylan and The Band Electrify Carnegie Hall On a crisp autumn night in New York City, October 1,

This Day in Pop Music History: October 1, 1965

Bob Dylan and The Band Electrify Carnegie Hall

On a crisp autumn night in New York City, October 1, 1965, the hallowed stage of Carnegie Hall bore witness to a musical metamorphosis. Bob Dylan, the poetic voice of a generation, stepped into the spotlight not as the lone troubadour of Greenwich Village, but as the frontman of a newly electrified ensemble. Backed by a group of Canadian-American musicians soon to be known simply as The Band, Dylan’s performance marked a turning point—not just in his own career, but in the trajectory of popular music itself.

This wasn’t just another concert. It was a cultural collision: folk purity meeting rock rebellion, lyrical introspection amplified through roaring amplifiers. The audience, a mix of loyal folk fans and curious newcomers, came expecting protest songs and acoustic ballads. What they got was something far more radical—a sonic revolution that would echo through the decades. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Setting the Stage: Folk’s Crown Prince Meets the Electric Storm

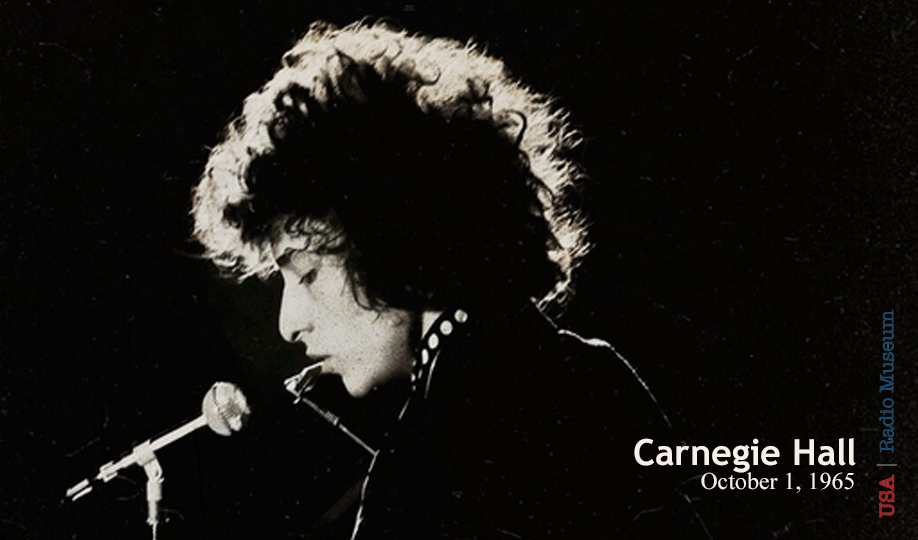

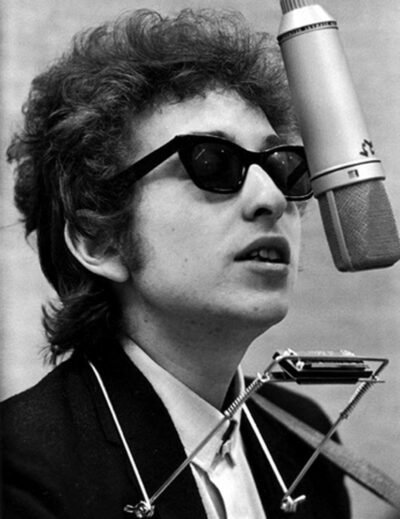

By 1965, Bob Dylan had already ascended to near-mythic status. His early albums—The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, The Times They Are A-Changin’, and Another Side of Bob Dylan—had positioned him as the conscience of the counterculture, a bard whose lyrics gave voice to civil rights marches, anti-war protests, and the restless spirit of youth. With his tousled hair, nasal drawl, and beatnik mystique, Dylan was the embodiment of folk authenticity.

But Dylan was never one to stand still.

In March of that year, he released Bringing It All Back Home, a split album that startled fans with its electric side. Then came Highway 61 Revisited in August—an unapologetically plugged-in masterpiece that opened with “Like a Rolling Stone,” a six-minute anthem that shattered radio norms and redefined what a pop single could be.

Behind the scenes, Dylan was assembling a new kind of band. He tapped into the raw energy of The Hawks, a group that had backed rockabilly wildman Ronnie Hawkins. Guitarist Robbie Robertson brought searing leads and a telepathic sense of timing. Garth Hudson, a classically trained organist, added swirling textures. Rick Danko’s bass lines danced with Richard Manuel’s piano, while Levon Helm’s drumming grounded it all with Southern grit. Together, they weren’t just a backing band—they were a force.

Carnegie Hall, with its velvet seats and classical pedigree, was an unlikely venue for this electric experiment. Yet Dylan chose it deliberately. It was a statement: this new sound wasn’t a detour—it was the future.

As the lights dimmed and Dylan walked onstage, guitar slung low, the air crackled with anticipation. He opened with solo acoustic numbers—“She Belongs to Me,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”—a nod to his roots. But then, midway through the set, the band emerged. The crowd murmured. Some leaned forward. Others bristled.

And then the storm hit.

The Night It Happened: October 1, 1965

Carnegie Hall had seen its share of legends—Tchaikovsky, Billie Holiday, Judy Garland—but on this night, it bore witness to a different kind of debut. Bob Dylan, freshly electrified and flanked by a band of musical outlaws, stepped into the lion’s den of folk orthodoxy and lit a fuse that would burn through the boundaries of genre, tradition, and expectation.

The evening began familiarly enough. Dylan took the stage alone, acoustic guitar in hand, harmonica rack around his neck. He opened with “She Belongs to Me,” followed by “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”—songs steeped in poetic ambiguity and emotional ache. The audience, largely composed of folk loyalists, settled into the comfort of Dylan’s introspective cadence.

But then came the pivot.

Midway through the set, Dylan turned to the crowd and introduced his new band. One by one, they emerged: Robbie Robertson with his Fender Telecaster, Garth Hudson behind a Lowrey organ, Rick Danko cradling his bass, Richard Manuel at the piano, and Levon Helm gripping his drumsticks. These weren’t session players—they were a unit, forged in the crucible of roadhouse gigs and rockabilly grit.

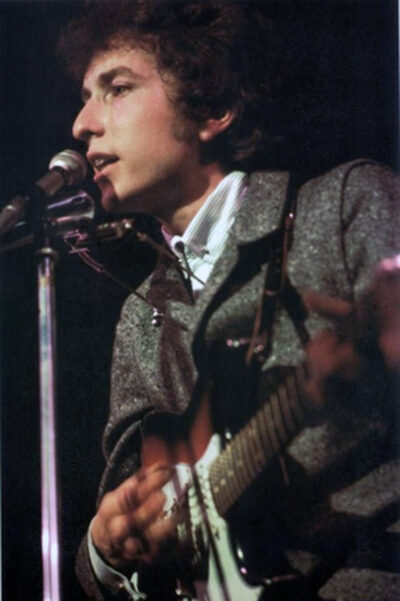

The first electric notes rang out like a challenge. “Tombstone Blues” roared through the hall, its surreal lyrics riding a wave of distortion and swagger. Dylan’s voice, once plaintive, now snarled with defiance. Robertson’s guitar sliced through the air, Helm’s drums thundered, and Hudson’s organ swirled like a psychedelic storm.

The reaction was instant—and divided.

Some fans cheered, swept up in the raw energy. Others sat stunned, betrayed by the man they’d crowned as folk’s messiah. A few booed, echoing the backlash Dylan had faced earlier that summer at the Newport Folk Festival. But Dylan didn’t flinch. He leaned into the chaos, delivering “Ballad of a Thin Man” with venomous precision, his lyrics a pointed indictment of those who couldn’t—or wouldn’t—understand the shift.

This wasn’t just a concert. It was a confrontation. Dylan was drawing a line in the sand, daring his audience to follow him into uncharted territory. And The Band? They weren’t just backing him—they were amplifying his rebellion, giving shape to a new sound that fused folk storytelling with rock’s visceral punch.

By the time the final notes faded, the room was changed. Carnegie Hall, once a bastion of musical tradition, had become a launchpad for revolution.

The Cultural Fallout: Folk Purists vs. Rock Revolutionaries

The Carnegie Hall concert on October 1, 1965 wasn’t just a musical event—it was a cultural fault line. In the months that followed, the tremors of Dylan’s electric turn reverberated across the folk community, dividing fans, critics, and fellow musicians into two camps: those who clung to the purity of acoustic protest, and those who embraced the raw, amplified future.

For folk purists, Dylan’s transformation felt like betrayal. He had been their voice, their poet laureate, the one who stood with Woody Guthrie’s ghost and sang truth to power. His shift to electric guitar and surrealist lyrics was seen as a sellout to commercialism, a rejection of the movement that had elevated him. Pete Seeger, a towering figure in the folk revival, famously bristled at Dylan’s electric set at Newport earlier that summer, reportedly threatening to cut the power cables with an axe. Though the story has been mythologized, it captured the emotional intensity of the moment.

For folk purists, Dylan’s transformation felt like betrayal. He had been their voice, their poet laureate, the one who stood with Woody Guthrie’s ghost and sang truth to power. His shift to electric guitar and surrealist lyrics was seen as a sellout to commercialism, a rejection of the movement that had elevated him. Pete Seeger, a towering figure in the folk revival, famously bristled at Dylan’s electric set at Newport earlier that summer, reportedly threatening to cut the power cables with an axe. Though the story has been mythologized, it captured the emotional intensity of the moment.

But Dylan wasn’t abandoning folk—he was expanding it.

With The Band behind him, Dylan fused the storytelling of folk with the urgency of rock. Songs like “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Highway 61 Revisited” didn’t just challenge musical norms—they challenged listeners to confront their own discomfort. The lyrics were cryptic, the sound aggressive, the message unapologetic: the times weren’t just changing—they were erupting.

The 1966 world tour, which followed the Carnegie Hall debut, became a crucible for this tension. Night after night, Dylan and The Band faced hostile crowds. In Manchester, England, a fan famously shouted “Judas!”—a moment immortalized on bootlegs and later official releases. Dylan’s response was legendary: “I don’t believe you… you’re a liar!” He turned to The Band and snarled, “Play it f***ing loud,” launching into a blistering version of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Through it all, The Band stood firm. Their musical cohesion, forged in the honky-tonks of Canada and the American South, gave Dylan the foundation he needed to weather the storm. They weren’t just sidemen—they were co-conspirators in a revolution.

Critics eventually caught up. What had seemed like heresy in 1965 was, by the end of the decade, hailed as visionary. Dylan’s electric trilogy—Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde—became canonical. The Band’s own debut, Music From Big Pink (1968), was embraced as a masterpiece of Americana, influencing everyone from George Harrison to Eric Clapton.

The cultural fallout had settled into a new landscape. Folk was no longer a genre defined by acoustic guitars and protest songs—it was a spirit, a sensibility, a commitment to truth-telling in whatever form the moment demanded.

And Dylan? He had proven that authenticity wasn’t about staying the same—it was about daring to evolve.

Interlude: From “The Hawks” to “The Band”

When Bob Dylan introduced his new backup group at Carnegie Hall on October 1, 1965, he didn’t call them “The Band.” He called them what they were at the time: Levon and The Hawks. The name carried echoes of their earlier life backing rockabilly firebrand Ronnie Hawkins, where they’d earned a reputation for tight musicianship and barroom grit.

But Dylan’s inner circle had already begun referring to them more simply—as “the band.” It was shorthand, casual, but telling. These weren’t just hired hands. They were collaborators, co-conspirators in Dylan’s electric rebellion. The chemistry was undeniable, and the nickname stuck.

By 1968, after years of touring, recording, and retreating to the creative sanctuary of Big Pink, Levon and The Hawks shed their old moniker and stepped into the spotlight as The Band. It was a name both humble and bold—suggesting unity, anonymity, and a kind of elemental musical force. No frills. No ego. Just five men making music that felt older than time and fresher than tomorrow.

Their transformation from backing group to headliners was seamless. With Music From Big Pink, they didn’t just arrive—they redefined the American sound. And it all began with that quiet introduction on a legendary stage: “Here’s my band.”

The Band’s Legacy: From Carnegie to Big Pink

When The Band stepped onto the Carnegie Hall stage in 1965, they were still anonymous to most of the audience—just five musicians backing Dylan’s electric experiment. But within a few short years, they would emerge as one of the most influential and revered groups in American music history.

Their journey from sidemen to legends began in earnest after the tumultuous 1966 tour. Retreating from the spotlight, Dylan and The Band holed up in a pink house in West Saugerties, New York—a modest, wood-framed home that would become mythologized as “Big Pink.” There, they recorded a sprawling collection of demos known as The Basement Tapes, blending folk, blues, country, and rock into a sound that felt timeless and distinctly American.

In 1968, The Band released their debut album, Music From Big Pink. It was a revelation. Songs like “The Weight,” “Tears of Rage,” and “I Shall Be Released” showcased their soulful harmonies, rustic instrumentation, and lyrical depth. The album was a quiet revolution—eschewing psychedelic excess for earthy authenticity. Critics hailed it as a masterpiece. Musicians were floored. Eric Clapton reportedly considered quitting Cream after hearing it, inspired to pursue a more roots-oriented sound.

Their follow-up, The Band (1969), cemented their status. With tracks like “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” and “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” they painted vivid portraits of American life—rural, haunted, resilient. The Band weren’t just making music; they were crafting folklore.

Each member brought something singular:

• Robbie Robertson, the chief songwriter, spun tales with cinematic scope.

• Levon Helm, the Arkansas-born drummer, gave voice to Southern characters with grit and grace.

• Rick Danko, his plaintive vocals and melodic bass added emotional weight.

• Richard Manuel, and his fragile tenor and piano work lent a ghostly beauty.

• Garth Hudson, the sonic architect, layered organ, clavinet, and saxophone into a rich tapestry.

Their influence rippled outward. Bruce Springsteen, Elton John, George Harrison, and countless others drew inspiration from their sound. They helped birth the genre now known as Americana, bridging the gap between rock and roots.

In 1976, The Band staged their farewell concert, The Last Waltz, at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. Directed by Martin Scorsese, the film captured their final bow with guests like Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, and Muddy Waters. It remains one of the most celebrated concert films of all time—a testament to their impact and artistry.

Though they began as Dylan’s backing band, by the end of the decade, The Band had carved out a legacy all their own. From Carnegie Hall to Big Pink, they redefined what it meant to be American musicians—grounded in tradition, yet unafraid to innovate.

Echoes in the Hall: Why October 1 Still Matters

Sixty years later, the echoes of Bob Dylan’s 1965 Carnegie Hall concert still reverberate—not just through the rafters of that storied venue, but through the soul of American music. It was a night that challenged tradition, redefined authenticity, and proved that evolution is not betrayal—it’s bravery.

For Dylan, October 1 wasn’t just a performance—it was a declaration. He stood at the crossroads of folk and rock, armed with poetry and distortion, and chose the path less traveled. In doing so, he gave permission to generations of artists to follow their muse, even when it led them into controversy.

For Dylan, October 1 wasn’t just a performance—it was a declaration. He stood at the crossroads of folk and rock, armed with poetry and distortion, and chose the path less traveled. In doing so, he gave permission to generations of artists to follow their muse, even when it led them into controversy.

For The Band, it was the beginning of a legacy that would stretch far beyond the role of backing musicians. Their chemistry, forged in dive bars and honed on the road, became the bedrock of a new American sound—one that honored tradition while carving out new terrain. Their presence that night wasn’t incidental; it was catalytic.

And for Carnegie Hall, the concert marked a moment of transformation. A venue once synonymous with classical refinement became a crucible for rebellion. The velvet seats bore witness to discomfort, defiance, and ultimately, transcendence.

Today, when artists plug in, shift genres, or challenge expectations, they walk in Dylan’s footsteps. When bands blend gospel harmonies with rock grit, they echo The Band’s blueprint. And when audiences wrestle with change, they reenact the tension of that October night.

The USA Radio Museum honors this moment not just as a historical footnote, but as a living memory—a reminder that music is meant to evolve, provoke, and inspire. October 1, 1965 wasn’t the end of folk. It was the beginning of something bigger: a sound that could hold contradiction, complexity, and courage.

As we reflect back to that Bob Dylan Carnegie Hall concert event in 1965—whether through audio, archival footage, or the crackle of vinyl—we don’t just hear notes. We hear a turning point. We hear Bob Dylan’s future arriving, and it was loud and unafraid.

_____________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.

I was present at that concert (at age12) and would like to make the following points. The article states that “The audience, a mix of loyal folk fans and curious newcomers, came expecting protest songs and acoustic ballads.” I’m not sure how the author knows what the audience members were thinking but I can confirm that neither myself or those I was with had such expectations. We had been listening to both “Bringing It All Back Home” and “Highway 61 Revisited” endlessly for months and as far as I can remember we were hoping for exactly what we got. We were completely turned on by that music and had largely moved on from the purely acoustic protest stuff. The author later states: “Some fans cheered, swept up in the raw energy. Others sat stunned, betrayed by the man they’d crowned as folk’s messiah. A few booed, echoing the backlash Dylan had faced earlier that summer at the Newport Folk Festival.” I can confirm that no one I talked to was stunned, nor was there any audible booing in the audience. This is just part of the mythology surrounding Dylan performances of that period which is repeated ad nauseam. The last point is that the lineup of Levon and the Hawks is mentioned as including Rick Danko on bass. Although he was indeed listed as the bass player in the printed program along with all the other members of what would become known as The Band, he was in fact, not present. I’m certain of this because the bass player that appeared with them that evening was African-American and I was aware at the time it couldn’t be him. I have long wondered at the identity of this presumably last-minute replacement (possibly Bill Lee?) and was hoping that this would finally be clarified in this article.

Subject: Thank You for Sharing Your Carnegie Hall Memories

Dear Savika,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful and detailed reflections on our recent USA Radio Museum article, “The Band Begins . . . October 1, 1965: A New Dylan Sound Takes the Stage.” Your firsthand account as a 12-year-old attendee at that historic Carnegie Hall concert is not only deeply appreciated—it’s invaluable.

Your insights help illuminate the lived experience of that night in ways no archival research ever could. We especially appreciate your clarification regarding audience expectations. While the article aimed to capture the broader cultural tension surrounding Dylan’s electric transition, your memory reminds us that many fans—yourself included—had already embraced Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited with open arms. That nuance matters, and we’re grateful you brought it forward.

Regarding the mention of booing and stunned reactions, you raise an important point about the mythology that often surrounds Dylan’s mid-60s performances. And it is legendary, a very much part of the Dylan folklore, if I may. While some accounts from other venues (like Newport and later in Europe) describe polarized reactions, your experience at Carnegie Hall suggests a more unified enthusiasm. We’ll be sure to revisit that framing in future editions and features. “Ad nauseam”? perhaps yes:

• A retrospective piece from Lakes Media Network acknowledges that Dylan’s electric performances “drew boos and abuse worldwide,” but it does not specifically confirm booing at Carnegie Hall.

• A 2023 article from CheatSheet describes booing at a 1965 concert in Queens, New York—not Carnegie Hall—and mentions fans invoking Ringo Starr’s name to mock Dylan’s Beatles-like sound. This suggests that while some New York audiences were resistant (based upon your expressed observations) Carnegie Hall may have been an exception. It seems as though that concert crowd may have been collectively reverent that evening!

And based on what is well known of the Dylan backlash (even Dylan wrote about it) we included it as well, of what was known at the time, to be a small part of this story. Most accounts of booing and backlash stem from Dylan’s earlier electric debut at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965 and his later 1966 world tour, especially in the UK. These events are well-documented in books like “No Direction Home” by Robert Shelton and “Chronicles: Volume One” by Dylan himself, which describe polarized reactions and audible jeers.

Your final note about the bass player is especially intriguing. The printed program listed Rick Danko, but your observation that an African-American musician played bass that evening opens a compelling question. The possibility of a last-minute substitution—perhaps Bill Lee (as you questioned) or another studio/session player—deserves further investigation. If you’re open to it, we’d love to follow up and explore this mystery together. Your memory may help us uncover a missing piece of music history.

On behalf of USA Radio Museum, thank you again for your generous comments contribution. We’re honored to have your voice as part of this ongoing tribute to Dylan, The Band, and the transformative power of live music, as you saw it as a 12-year-old firsthand, in October, 1965.

Warm regards,

Jim Feliciano

USA Radio Museum

Preserving the Soundtrack of Our Lives