Introduction: The Birth of FM Radio How clarity, culture, and counterculture crowned a new king of the dial The story of FM radio doesn’

Introduction: The Birth of FM Radio

How clarity, culture, and counterculture crowned a new king of the dial

The story of FM radio doesn’t begin with a commercial breakthrough or corporate backing. It begins with one man’s stubborn brilliance and a fundamental question: Why should radio be filled with static? Edwin Howard Armstrong, a visionary inventor already responsible for the super heterodyne receiver—a device that revolutionized radio reception—set out in 1933 to solve the persistent hums, pops, and interference that plagued AM radio. What he created wasn’t just an alternative—it was a technological leap forward. He called it Frequency Modulation: FM.

Unlike AM radio, which encodes audio by modulating the amplitude of its signal, FM achieved its stunning clarity by modulating the frequency instead. This made FM transmissions far more resilient to atmospheric noise and electrical interference—transforming radio into something cleaner, richer, and altogether more immersive.

Unlike AM radio, which encodes audio by modulating the amplitude of its signal, FM achieved its stunning clarity by modulating the frequency instead. This made FM transmissions far more resilient to atmospheric noise and electrical interference—transforming radio into something cleaner, richer, and altogether more immersive.

But brilliance doesn’t always translate into immediate success.

Armstrong’s innovation quickly drew the attention—and the ire—of the broadcasting establishment. Chief among the skeptics and opponents was David Sarnoff, the powerful head of RCA. Sarnoff had staked his empire’s fortunes on AM radio and the burgeoning medium of television. FM posed a threat to both. Rather than invest in the new technology, RCA leveraged its influence to sideline it, keeping FM off the market and away from consumers for years. Armstrong, once Sarnoff’s protégé, now found himself fighting an uphill battle against corporate resistance and regulatory inertia.

That battle turned crueler in 1945 when the FCC dealt FM its most crippling blow yet. In a sweeping postwar reorganization of the radio spectrum, the commission abruptly moved the FM band from its original 42–50 MHz range to a new 88–108 MHz range. The rationale was framed as progress, but the result was devastating: every FM receiver sold to date was instantly outdated. Tens of thousands of devices became obsolete overnight. The industry stalled, and Armstrong’s dream teetered on the edge.

Still, FM would not disappear.

In the 1950s, a quiet momentum began to build. Enthusiasts, audiophiles, and independent broadcasters recognized FM’s potential—especially for music. Its clarity was unmatched. Its dynamic range allowed orchestras, jazz quartets, and vocalists to shimmer across the dial in a way AM could never replicate. As more stations embraced the format, FM began to find an audience. By the early 1960s, a new chapter opened: one that would change everything.

In 1961, the FCC approved multiplex stereo broadcasting on FM. With that ruling, FM wasn’t just better than AM—it was transformational. Stereo broadcasts gave listeners dimension, depth, and directionality. Music could now move—left to right, foreground to background. For fans of jazz, classical, and the emerging wave of rock, FM became the destination. No longer defined by legal battles or backroom resistance, it was defined by sound—glorious, stereo sound.

From its invention in the shadow of the Empire State Building to its stereo rebirth three decades later, FM’s journey was marked by conflict, clarity, and eventual triumph. What began as a rebellion against interference became the new gold standard for music radio—and a defining voice in 20th-century culture.

FM’s Forgotten Years: 1933–1959

From Spark to Static-Free Signal

Before FM radio reshaped America’s soundscape in the 1960s, it lived a quieter life in the shadows—a passion project nurtured by one visionary and a small constellation of true believers. What would later become the dominant force in music radio began as a single, stubborn quest for clarity in a world full of static.

Before FM radio reshaped America’s soundscape in the 1960s, it lived a quieter life in the shadows—a passion project nurtured by one visionary and a small constellation of true believers. What would later become the dominant force in music radio began as a single, stubborn quest for clarity in a world full of static.

That quest belonged to Edwin Howard Armstrong.

In 1933, Armstrong, a brilliant Columbia University engineering professor already celebrated for inventing the super heterodyne receiver, announced his most groundbreaking creation yet: frequency modulation. FM wasn’t just a technical upgrade—it was a reimagining of how sound could ride the air. Unlike AM, which encoded signals by varying amplitude (making it highly susceptible to noise), FM changed the frequency of the carrier wave. This shift dramatically reduced interference and offered crisp, rich audio that AM simply couldn’t touch.

But for Armstrong, invention wasn’t enough. He needed to prove FM.

In 1937, he constructed a tower atop the Palisades in Alpine, New Jersey, and launched an experimental FM station, W2XMN. From its summit overlooking the Hudson River, W2XMN broadcast music with fidelity never before heard on the airwaves. On July 18, 1939, that signal officially went live to the public—America’s first regular FM broadcast. It was relayed to WQXR in New York City, where it delivered classical selections by Tchaikovsky and Haydn to a tiny, but captivated audience. There were just 25 FM receivers in existence that day, but those who tuned in heard something remarkable: a future without static.

Encouraged by the promise, the FCC began licensing FM stations. On March 1, 1941, Nashville’s W47NV signed on as the first official commercial FM outlet in the country. Broadcasting at 44.7 MHz, it served as a beacon that FM could thrive outside experimental circles. For a brief moment, momentum flickered to life.

But powerful interests had no intention of letting FM take hold.

At the center of the opposition was David Sarnoff, the commanding head of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Sarnoff saw FM not as a marvel, but as a threat—one that could disrupt RCA’s investment in both AM radio and the rapidly developing technology of television. Once a patron to Armstrong, Sarnoff became a roadblock. RCA withheld support, stalled development, and promoted television as the next great evolution of broadcasting. In the corridors of power and policy, FM was quietly boxed out.

Then came the most devastating blow of all.

In 1945, the FCC—pressured in part by RCA’s lobbying—reassigned the FM frequency band. Originally set between 42 and 50 MHz, FM was moved to a new space on the spectrum: 88 to 108 MHz. The stated reason was spectrum reallocation, but the consequence was catastrophic. All existing FM equipment, including Armstrong’s early receivers and transmitters, became obsolete overnight. Listeners who had invested in the new technology were left with radios that could no longer receive broadcasts. FM’s fledgling infrastructure was effectively gutted.

In the aftermath, FM didn’t vanish—but it retreated. Through the late 1940s and into the 1950s, it lived on in niche corners of the dial. Classical music found a quiet home there. Universities and educators established noncommercial FM stations to explore public-service broadcasting and cultural programming. Audio purists and hobbyists, drawn by FM’s superior sound, kept the faith. Some broadcasters launched background-music services—early precursors to Muzak—giving FM a presence in offices, stores, and elevators.

Yet it was a slow, uphill journey. Without widespread consumer adoption or industry support, FM struggled to flourish.

Tragically, the weight of legal battles, financial ruin, and professional betrayal took its toll on Armstrong. In 1954, he ended his life at the age of 63—an inventor whose greatest triumph had yet to receive its due. But his legacy refused to die.

In the years that followed, FM’s unique fidelity and potential would find new champions. Stereo was just around the corner. So were the counterculture, progressive formats, and a public that would soon demand something more from radio. And when that moment arrived, FM was ready—thanks to a foundation built during these quiet, overlooked years.

What began atop a New Jersey cliff wasn’t a failed broadcast—it was a spark. And eventually, it would set the airwaves on fire

FM’s First Steps: The 1940s and 1950s

Though Edwin Howard Armstrong’s invention of frequency modulation in 1933 opened the door to a new age of static-free broadcasting, FM’s first two decades were marked more by struggle than by success. The world was on the brink of war, RCA had an iron grip on the existing radio industry, and FM was still an unproven upstart with few commercial backers. Yet quietly, despite systemic resistance, FM took its first bold steps.

Though Edwin Howard Armstrong’s invention of frequency modulation in 1933 opened the door to a new age of static-free broadcasting, FM’s first two decades were marked more by struggle than by success. The world was on the brink of war, RCA had an iron grip on the existing radio industry, and FM was still an unproven upstart with few commercial backers. Yet quietly, despite systemic resistance, FM took its first bold steps.

In 1941, the FCC granted the first commercial FM license to a station in Nashville, Tennessee, designated W47NV. The station was primarily focused on classical programming and represented a hopeful early test case for FM’s commercial potential. At that time, FM broadcasting operated within the 42 to 50 megahertz (MHz) frequency band. But just four years later, in 1945, the FCC made a decision that would significantly delay FM’s development. The commission reassigned the entire FM band to a new spectrum—88 to 108 MHz—effectively making all existing FM radios obsolete. Broadcasters and listeners who had adopted the technology early were left behind, and manufacturers had to start over. Though justified as part of broader spectrum reallocation following the war, this move set FM’s progress back nearly a decade.

Adding to FM’s uphill battle was resistance from powerful corporate stakeholders, most notably David Sarnoff, chairman of RCA. Sarnoff had once backed Armstrong’s earlier inventions but saw FM as a threat to RCA’s dominance in both AM radio and the emerging market for television. RCA refused to license Armstrong’s technology, actively fought him in court, and instead championed its own, inferior wide-band AM alternatives. The company’s lobbying efforts, patent disputes, and refusal to support FM manufacturing stalled widespread adoption and left Armstrong isolated in his battle for recognition.

The Second World War only compounded these setbacks. With manufacturing resources redirected toward military efforts, the production of FM receivers and transmitters ground to a near halt. FM’s rollout, already precarious, was put on indefinite pause. When the war ended, things didn’t immediately improve. By 1950, only 691 FM stations were operating in the United States—most of them poorly funded and barely hanging on. FM’s content was largely limited to classical music, educational lectures, or instrumental background programming, often billed as “elevator music.” The revolutionary fidelity of FM wasn’t yet matched by revolutionary programming.

Then, in 1954, came the most tragic moment in FM’s early history. After years of battling lawsuits, financial strain, and corporate suppression, Edwin Howard Armstrong died by suicide. He left behind not only a grieving widow but a medium many believed would fade with him. It was a devastating turn for a man who had revolutionized the way humans communicated—first with the regenerative circuit, then the super heterodyne receiver, and finally, with FM radio itself.

Yet, despite the hardship and heartbreak, FM would not be buried. Quietly, it remained on the dial. Tinkerers and hi-fi enthusiasts kept the flame alive. A few public institutions continued to experiment with stereo transmission. And as the 1950s gave way to a new decade of cultural upheaval and audio innovation, FM’s moment was drawing closer.

Bridging to a Boom: The Seeds of the Sixties

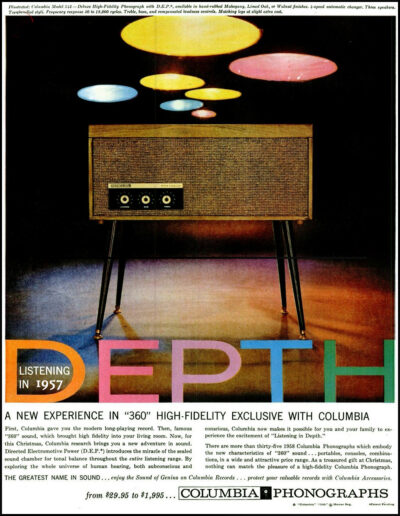

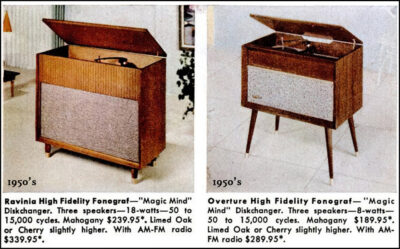

As the 1950s faded and America found itself straddling the optimism of postwar prosperity and the cultural rumbles of a new generation, FM radio remained a largely underappreciated whisper on the dial. It still lived on the fringes—tucked into the wooden frames of hi-fi consoles, beloved by audio purists, and largely overshadowed by television and the continued dominance of AM radio.

As the 1950s faded and America found itself straddling the optimism of postwar prosperity and the cultural rumbles of a new generation, FM radio remained a largely underappreciated whisper on the dial. It still lived on the fringes—tucked into the wooden frames of hi-fi consoles, beloved by audio purists, and largely overshadowed by television and the continued dominance of AM radio.

But even as mainstream media overlooked FM, two transformative forces were quietly gathering momentum. By the early 1960s, they would converge to ignite a new era of broadcasting, one that would finally deliver on the promise that Edwin Armstrong had envisioned decades earlier.

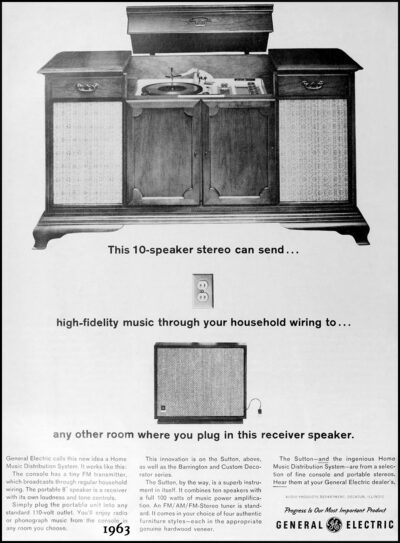

The first catalyst came in the form of sound itself. In 1961, the Federal Communications Commission officially approved multiplex stereo transmission for FM broadcasting. It was a technical milestone that let stations transmit separate left and right audio channels, producing a listening experience with space, depth, and nuance—something AM radio simply couldn’t replicate. For music lovers and equipment aficionados, this wasn’t just an improvement; it was a revelation. Suddenly, recordings didn’t just play—they came alive. The acoustics of a concert hall, the intimacy of a jazz trio, the shimmer of strings across a stereo soundstage were no longer confined to the grooves of a record—they were now available over the airwaves. Stereo FM made hi-fi portable, accessible, and communal.

Yet sound alone wasn’t enough. The second—and perhaps more decisive—shift came from a regulatory nudge that soon became a shove. In the early 1960s, the FCC began encouraging AM and FM combination stations to break from their habit of simulcasting the same content across both bands. At the time, most FM stations simply mirrored their AM counterparts, offering little incentive for listeners to tune in. But the FCC believed that FM deserved its own identity, its own programming, its own audience. By 1965, this encouragement escalated into formal pressure, as the Commission began preparing rules to require separate content—especially in larger markets where FM had growth potential.

These two developments—stereo broadcasting and a push for independent programming—laid the groundwork for an FM renaissance. They offered both a technological advantage and a regulatory pathway for FM to finally differentiate itself from AM and build a distinct cultural presence. They were, in essence, the seeds of the FM boom. And while the world may not have noticed it yet, the dial was already beginning to turn.

1963: FM Stereo Sparks a Revolution

By the summer of 1963, the FM dial was beginning to stir with promise. After decades of obscurity, and only two years since the FCC approved multiplex stereo broadcasting, FM was experiencing a bona fide sales boom. According to Billboard’s June 29, 1963 issue, industry projections estimated that over one million stereo-capable FM receivers would be sold in that year alone. It was a remarkable figure—especially for a medium that had only recently stepped out of AM radio’s shadow. As Billboard put it with characteristic punch: “Not bad for a medium celebrating its second birthday.”

By the summer of 1963, the FM dial was beginning to stir with promise. After decades of obscurity, and only two years since the FCC approved multiplex stereo broadcasting, FM was experiencing a bona fide sales boom. According to Billboard’s June 29, 1963 issue, industry projections estimated that over one million stereo-capable FM receivers would be sold in that year alone. It was a remarkable figure—especially for a medium that had only recently stepped out of AM radio’s shadow. As Billboard put it with characteristic punch: “Not bad for a medium celebrating its second birthday.”

This sudden demand wasn’t just a fluke of marketing—it was a reflection of seismic shifts happening across the radio landscape. FM’s high-fidelity sound was finally reaching the ears of the public, and they liked what they heard. Tables, portables, clock radios, component tuners, and imported models all saw increased production and enthusiastic uptake from consumers. Retailers reported strong demand across virtually every category of FM device, signaling a change in listener behavior and commercial viability.

At the heart of this expansion was a dramatic increase in FM infrastructure. That year, 228 FM stereo stations were broadcasting across 44 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The signals weren’t just concentrated in major metro centers, either. From heavily populated coastlines to quieter towns nestled in the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, FM stereo signals were being heard—and more importantly, being sought out.

The strongest hotspots emerged quickly. San Francisco, long regarded as one of the most vibrant FM markets in the country, was preparing to become the nation’s first city with eight FM stereo stations on the air. Detroit, always a forward-leaning radio town, had six. Seattle, Chicago, and Philadelphia boasted at least five stations each. Los Angeles and Houston were growing rapidly. Even smaller cities like Eugene-Springfield, Oregon and Grand Rapids, Michigan saw early investment and enthusiastic listenership.

But FM stereo wasn’t just a broadcast revolution—it was changing home entertainment itself. Across the country, living rooms were outfitted with hi-fi stereo consoles and combo phonograph-radio units that delivered FM stereo with rich, room-filling clarity. It was no longer enough to just listen to music; the experience became immersive, emotional, and almost tactile. FM had transformed into more than just a technology—it had become a lifestyle. For the American consumer in 1963, buying an FM stereo system wasn’t simply keeping up with a trend—it was an invitation to “come hear the future.”

Looking back, 1963 stands as one of the most critical turning points in FM history. It was the moment when the signal grew loud enough to be noticed, clear enough to be loved, and widespread enough to start a movement. The countdown to FM’s cultural breakthrough had begun—and the radio landscape would never be the same.

_____________________

To Be Continued . . . .

This concludes Part One of our in-depth look at FM’s extraordinary journey—from a static-free spark in Alpine to the first crackles of revolution on the American dial. But the broadcast doesn’t stop here.

Part Two—tracing FM’s cultural explosion, stereo triumph, and its ultimate rise over AM—1964 on— will be published on Wednesday, July 2, 2025. In our conclusion, stay tuned as we dive deeper into the golden decades that shaped the way America listens, learns, and lives through the airwaves.

Because when the dial turns, the story continues . . . .

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view.

![From Static to Stereo: The Birth, Rise and Reign of FM Radio [Part One] From Static to Stereo: The Birth, Rise and Reign of FM Radio [Part One]](https://usaradiomuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-Birth-of-the-FM-Sound-Part-One-USARM-01-2025.jpg)

Ahem! Don’t forget Cincinnati Jim for they would start the FM revolution, when lawyer and attorney Frank Wood launched WEBN on August the 31st of 1967.

And don’t forget about the FM wasn’t just the king but also the queen of the dial too as well!