Introduction: The Night Radio Shook America's Airways On the evening of October 30, 1938, as jack-o’-lanterns flickered and families gathered aroun

Introduction: The Night Radio Shook America’s Airways

On the evening of October 30, 1938, as jack-o’-lanterns flickered and families gathered around their living room radios, a young theatrical prodigy named Orson Welles ignited one of the most unforgettable moments in broadcast history. His adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, aired live on CBS as part of The Mercury Theatre on the Air, was not just a radio drama—it was a masterstroke of sonic illusion.

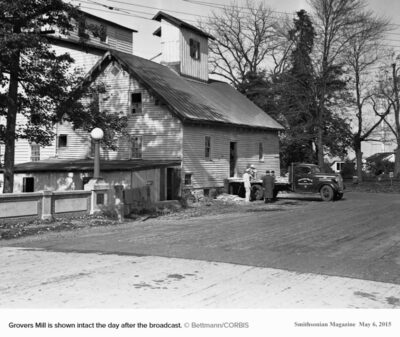

Presented as a series of breaking news bulletins, the program described an unfolding Martian invasion in chilling detail. The realism was uncanny: listeners heard reports of strange explosions on Mars, a cylinder crashing into Grovers Mill, New Jersey, and the horrifying emergence of tripod war machines unleashing heat rays on helpless citizens. The broadcast’s pacing, sound design, and deadpan delivery blurred the line between fiction and fact so convincingly that thousands of Americans believed the invasion was real.

Panic spread. Some fled their homes. Others called police stations, newspapers, and neighbors in a frenzy. Though later accounts would debate the scale of the hysteria, there was no denying the impact: radio had proven its power not just to inform or entertain, but to unsettle, to provoke, and to transform public perception in real time.

At just 23 years old, Orson Welles had orchestrated a cultural earthquake. What began as a Halloween experiment in storytelling became a defining moment in media history—a cautionary tale, a legend, and a testament to the emotional force of sound.

This article revisits that night in full: the artistry behind the broadcast, the myth of the panic, the rise of Welles, and the legacy that still echoes through the airwaves. With the USA Radio Museum’s complete archival recording embedded, we invite you to relive the moment America mistook fiction for fact—and radio became a mirror to our deepest fears. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

The Broadcast: Anatomy of a Hoax

At 8 p.m. Eastern on October 30, 1938, the Columbia Broadcasting System aired what was billed as a Halloween episode of The Mercury Theatre on the Air. The program began innocuously enough: an introduction by announcer Dan Seymour, followed by a fictional weather report and a musical interlude from Ramón Raquello and his orchestra—actually a studio ensemble led by Bernard Herrmann, Welles’ future film composer.

At 8 p.m. Eastern on October 30, 1938, the Columbia Broadcasting System aired what was billed as a Halloween episode of The Mercury Theatre on the Air. The program began innocuously enough: an introduction by announcer Dan Seymour, followed by a fictional weather report and a musical interlude from Ramón Raquello and his orchestra—actually a studio ensemble led by Bernard Herrmann, Welles’ future film composer.

Then came the first “news bulletin.”

A series of increasingly frantic interruptions described strange explosions on Mars, a meteorite landing in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, and the emergence of monstrous Martians wielding heat rays. The pacing was masterful: calm narration gave way to chaos, with reporters “on the scene” gasping for breath, describing the destruction of National Guard units, and eventually falling silent—implying their deaths.

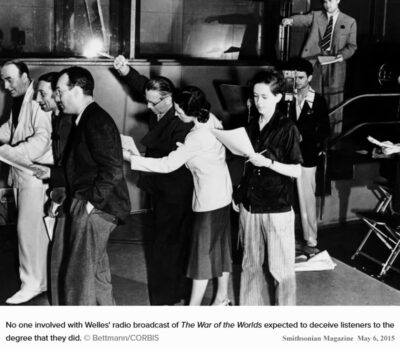

The realism was uncanny. Welles and his team had studied actual news broadcasts to mimic their cadence and structure. They used long silences, static bursts, and overlapping voices to simulate live reporting. The actors, including Frank Readick as the doomed field reporter Carl Phillips, delivered their lines with such conviction that many listeners believed they were hearing a real invasion unfold.

The broadcast’s structure was key to its impact:

• First 20 minutes: Presented entirely as a simulated news report, with no commercial breaks or disclaimers.

• Middle section: Shifted to a more traditional radio drama format, following a survivor’s account and government response.

• Final act: A philosophical monologue by Welles as Professor Pierson, reflecting on humanity’s resilience and the Martians’ downfall due to Earth’s bacteria.

Though the program did include a disclaimer at the beginning—and another at the end—many listeners tuned in late, missing the warning. Compounding the confusion, the Mercury Theatre aired opposite The Chase and Sanborn Hour, a popular variety show. When listeners switched stations during a musical number, they landed mid-invasion, with no context.

Though the program did include a disclaimer at the beginning—and another at the end—many listeners tuned in late, missing the warning. Compounding the confusion, the Mercury Theatre aired opposite The Chase and Sanborn Hour, a popular variety show. When listeners switched stations during a musical number, they landed mid-invasion, with no context.

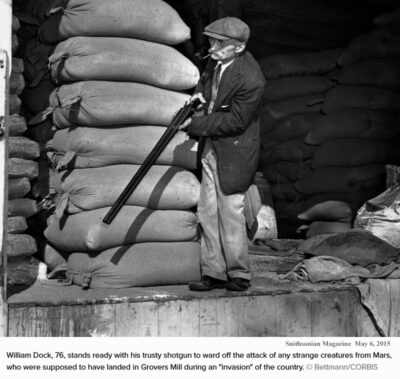

The illusion was so complete that even seasoned journalists were fooled. Some CBS affiliates reportedly called the network in panic. Police departments fielded calls from frightened citizens. In New Jersey, residents of Grover’s Mill armed themselves, believing the Martians had landed nearby.

Welles, seated at the microphone in Studio One at CBS’s New York headquarters, remained calm throughout. He had no idea the broadcast was causing such a stir—until the phones began ringing and network executives rushed in.

The program ended with Welles breaking character and assuring listeners it was all fiction. “This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “out of character to assure you that The War of the Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be.”

But the damage—or the legend—was already done.

_____________________

Sidebar: The Mercury Theatre On The Air

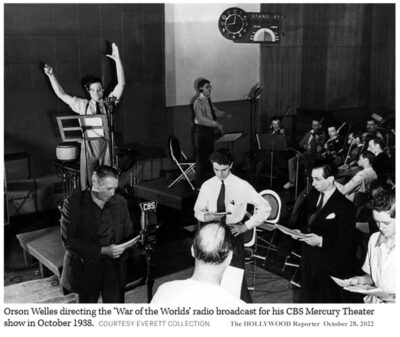

The Mercury Theatre on the Air’s legendary War of the Worlds broadcast was performed and aired live from New York City on October 30, 1938.

Specifically, the program originated from the Columbia Broadcasting Building at 485 Madison Avenue, the CBS Radio headquarters in Manhattan. Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre troupe—including Frank Readick, Kenny Delmar, and Ray Collins—performed the entire drama from Studio One, a space known for its acoustics and technical sophistication.

This New York studio was the epicenter of the broadcast that shook the nation. From that room, Welles’ voice traveled coast to coast, turning fiction into fear and cementing radio’s power as a storytelling force.

_____________________

The Reaction: Panic or Press Hysteria?

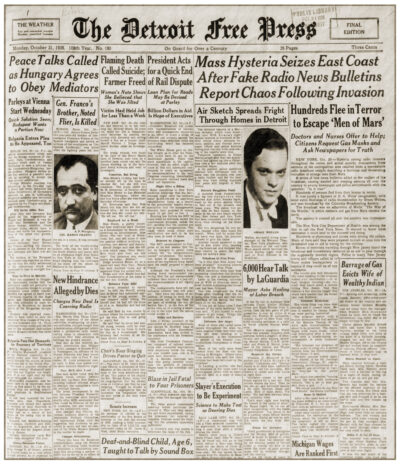

In the hours following the War of the Worlds broadcast, America awoke to headlines that screamed of chaos. “Radio Fake Scares Nation,” blared the Chicago Herald-Examiner. “Thousands Flee Homes,” claimed the New York Daily News. The narrative was irresistible: a Halloween prank had spiraled into mass hysteria, exposing the vulnerability of a nation gripped by fear.

But how much of it was true?

The Immediate Fallout

CBS was inundated with phone calls. Police stations across the country reported a surge in inquiries. In Grover’s Mill, New Jersey—the fictional landing site of the Martians—residents reportedly armed themselves and patrolled the woods. One farmer even fired a shotgun at a water tower, mistaking it for an alien war machine.

CBS was inundated with phone calls. Police stations across the country reported a surge in inquiries. In Grover’s Mill, New Jersey—the fictional landing site of the Martians—residents reportedly armed themselves and patrolled the woods. One farmer even fired a shotgun at a water tower, mistaking it for an alien war machine.

In New York, some listeners allegedly packed their cars and fled the city. Others called newspapers, demanding to know if the country was under attack. Hospitals claimed to have treated patients for shock. The Federal Communications Commission launched an investigation, and CBS executives scrambled to contain the fallout.

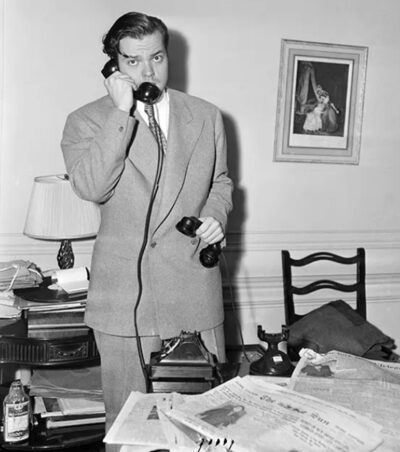

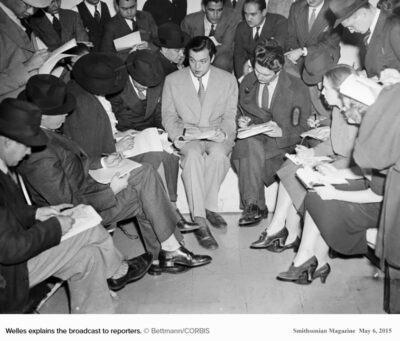

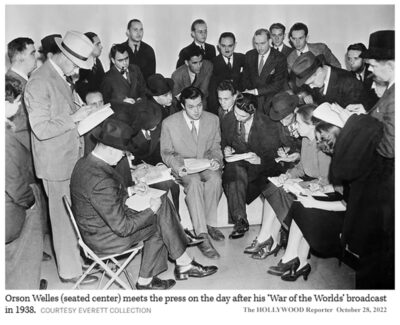

Orson Welles, meanwhile, faced a media firestorm. At a press conference the next day, he feigned surprise and remorse, though some accounts suggest he was privately delighted by the attention. “I didn’t mean to frighten people,” he said, “just to entertain them.”

The Myth of Mass Panic

Yet as scholars later discovered, the scale of the panic may have been exaggerated. In 1940, Princeton’s Hadley Cantril conducted a study estimating that 1.2 million people were “frightened” by the broadcast—but only a fraction took action. Many listeners were skeptical, and others quickly realized it was fiction.

So why the hysteria?

The answer lies in the rivalry between newspapers and radio. In 1938, print media was losing ground to the immediacy and intimacy of radio. The War of the Worlds incident gave newspapers a golden opportunity to discredit their new competitor. By amplifying the panic, they painted radio as irresponsible and dangerous—a medium that could not be trusted.

This media framing shaped public memory. For decades, the broadcast was remembered not just as a brilliant piece of drama, but as a cautionary tale about gullibility and the power of mass communication.

Emotional Undercurrents

It’s easy to laugh at the idea of Martians causing a stampede. But beneath the surface, the reaction revealed something deeper: a nation on edge. In 1938, war loomed in Europe. The Great Depression had left scars. The idea of an invasion—any invasion—was not so far-fetched.

Radio, with its disembodied voices and invisible authority, tapped into those anxieties. Welles didn’t just tell a story; he held up a mirror to America’s fears. And for one night, the reflection was terrifying.

Local Fallout: Detroit Reacts to the Broadcast

On the morning of Monday, October 31, 1938, aside of the related front-page headline, the Detroit Free Press also published an additional article that captured the city’s stunned reaction: “AIR SKETCH SPREADS FRIGHT THROUGH HOMES IN DETROIT.” The previous night, WJR had aired Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast, and what followed was a wave of confusion, panic, and disbelief that swept through hundreds of homes across Michigan.

The Detroit Free Press, Monday, October 31, 1938. (A viewing tip: Click this digitized image 2x in second window for largest detailed, expanded PC read.)

As fictional reports of a Martian invasion crackled over the airwaves, Detroit listeners flooded newspaper offices and police stations with frantic calls. At Police Headquarters, the switchboard lit up “like a Christmas tree” within minutes of the broadcast’s start. Operators, initially puzzled, checked with reporters and quickly learned that the invasion was merely a radio thriller. For the next hour, they reassured callers that peace still reigned in New Jersey.

In Ann Arbor, a motorist from Pennsylvania arrived at the police station with his two daughters, visibly shaken. He had heard reports that New Jersey and New York had fallen to Martian forces and feared the monsters were advancing toward his home state. His daughters fainted in fear, and though police confirmed the broadcast was fictional, the man refused to give his name. Another couple, equally alarmed, asked to spend the night in jail for safety.

The Free Press received a flood of inquiries: “Is it true that New Jersey has been invaded?” WJR operators worked tirelessly to calm listeners, repeating, “That was just a dramatization.”

Later in the evening, station announcers issued periodic bulletins clarifying that the broadcast was fictional. One man, after learning the truth, called the paper to report that two members of his family had fallen ill from the shock. “I put myself to extra expense to get home,” he said. “Things like that shouldn’t be allowed.”

Not all reactions were sympathetic. Some callers expressed anger, threatening to file complaints with the Federal Communications Commission. Many were visitors from the East, while others were distraught mothers whose children had been terrorized by the broadcast. In Lansing, one mother without a telephone rushed to a newspaper office with her eight-year-old child, who was described as being in a state of near-collapse.

This local account from Detroit underscores the emotional power of radio in 1938—and the trust listeners placed in the voices that came through their speakers. In Michigan, the panic wasn’t just national—it was deeply personal.

Orson Welles: The Boy Wonder of Radio

In 1938, Orson Welles was just 23 years old—but already a force of nature. With a baritone voice that belied his age and a theatrical imagination that defied convention, Welles had carved out a reputation as a prodigy of the stage and microphone. The War of the Worlds broadcast would catapult him from rising star to national sensation, but the seeds of that moment were sown long before Halloween night.

In 1938, Orson Welles was just 23 years old—but already a force of nature. With a baritone voice that belied his age and a theatrical imagination that defied convention, Welles had carved out a reputation as a prodigy of the stage and microphone. The War of the Worlds broadcast would catapult him from rising star to national sensation, but the seeds of that moment were sown long before Halloween night.

A Theatrical Meteor

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in 1915, Welles was a precocious child—reading Shakespeare by age seven, painting, composing, and performing with a flair that stunned his teachers. After a brief stint in Ireland’s Gate Theatre and a whirlwind of stage work in New York, he co-founded the Mercury Theatre in 1937 with producer John Houseman. Their productions were bold, modern, and politically charged—none more so than their all-Black Macbeth, set in Haiti and staged in Harlem.

Welles’ radio career blossomed in parallel. His voice—velvety, commanding, and endlessly expressive—made him a natural for the medium. He voiced The Shadow, narrated documentaries, and brought literary classics to life on The Mercury Theatre on the Air, a weekly CBS series that adapted works like Dracula, Treasure Island, and Jane Eyre.

But it was The War of the Worlds that changed everything.

The Architect of Illusion

Welles didn’t write the script—that credit goes to Howard Koch—but he directed and shaped it with cinematic precision. He understood radio’s unique power: the way it bypassed the eyes and went straight to the imagination. By stripping away narration and presenting the story as a series of news bulletins, Welles created a new kind of drama—one that felt real because it sounded real.

He rehearsed his cast meticulously, coached them to underplay their lines, and layered the sound design with eerie realism. The result was not just a performance—it was an experience. Welles had turned the airwaves into a stage, and the nation into his audience.

Fame, Fallout, and the Road to Hollywood

The morning after the broadcast, Welles faced a media frenzy. At a press conference hastily arranged by CBS, he appeared contrite—wide-eyed, soft-spoken, and seemingly overwhelmed by the reaction. But behind the scenes, he understood the magnitude of what he’d done. He had proven that radio could rival film and theater in emotional impact—and that he could command it.

The morning after the broadcast, Welles faced a media frenzy. At a press conference hastily arranged by CBS, he appeared contrite—wide-eyed, soft-spoken, and seemingly overwhelmed by the reaction. But behind the scenes, he understood the magnitude of what he’d done. He had proven that radio could rival film and theater in emotional impact—and that he could command it.

Hollywood took notice. Within months, Welles signed an unprecedented contract with RKO Pictures: full creative control, final cut, and the freedom to write, direct, produce, and star in his own films. The result was Citizen Kane (1941), widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

But Welles’ relationship with power—creative, institutional, and political—would remain turbulent. He was a maverick, often at odds with studios, critics, and even his own collaborators. Yet his legacy was sealed: a visionary who redefined every medium he touched.

The Voice That Echoes

For the USA Radio Museum, Welles represents more than a moment of panic or a Halloween stunt. He embodies the artistic potential of radio—the ability to conjure entire worlds with nothing but sound. His War of the Worlds broadcast remains a masterclass in storytelling, a reminder that the most powerful illusions are the ones we choose to believe.

Media Ethics and the Birth of Broadcast Responsibility

The morning after Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds aired, America wasn’t just talking about Martians. It was talking about radio itself—its influence, its boundaries, and its obligations. What had begun as a Halloween drama had triggered a reckoning: could a medium so intimate, so persuasive, be trusted with the truth?

The FCC Steps In

Though no formal penalties were issued, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) launched an immediate inquiry. CBS executives were summoned to explain how a fictional broadcast had caused such widespread confusion. The network defended the program as artistic expression, but the incident prompted internal reviews and new cautionary policies.

Broadcasters began to rethink the structure of dramatic programming. Disclaimers became more prominent. Realistic formats—especially those mimicking news—were scrutinized. The idea that radio could “accidentally deceive” the public was now a regulatory concern.

The Ethics of Illusion

At the heart of the debate was a question that still resonates: where is the line between realism and manipulation?

At the heart of the debate was a question that still resonates: where is the line between realism and manipulation?

Welles had not intended to deceive maliciously. His goal was immersion, not misinformation. But the broadcast’s format—news bulletins, eyewitness accounts, official statements—blurred the boundary between fiction and reportage. It was a masterclass in verisimilitude, but also a cautionary tale.

Critics argued that Welles had exploited public trust. Radio, after all, was the voice of authority in 1938. It delivered presidential addresses, war updates, and emergency alerts. To mimic that voice for entertainment, some said, was irresponsible.

Supporters countered that the audience bore some responsibility. The broadcast included disclaimers. The Mercury Theatre was known for dramatizations. And the panic, they argued, was fueled more by media amplification than by the broadcast itself.

A New Era of Broadcast Standards

In the wake of the incident, networks adopted stricter guidelines:

• Clear disclaimers before and during fictional programs

• Avoidance of real place names in dramatic contexts

• Limits on simulated news formats without explicit framing

These standards helped shape the ethical framework of American broadcasting. They acknowledged radio’s power—not just to entertain, but to influence perception and behavior.

The Legacy of Responsibility

For the USA Radio Museum, this moment marks a turning point. The War of the Worlds wasn’t just a broadcast—it was a mirror held up to the medium itself. It forced radio to confront its own potency, to reckon with the trust it commanded, and to evolve in response.

Today, as we navigate new frontiers in media—from deepfakes to AI-generated content—the questions raised in 1938 remain strikingly relevant. What do we believe? Who do we trust? And how do we balance creativity with accountability?

Orson Welles didn’t just scare America. He made it think. And in doing so, he helped shape the ethical spine of modern broadcasting.

Legacy: Why It Still Matters

More than eight decades after Orson Welles’ voice crackled across the airwaves, The War of the Worlds remains one of the most studied, celebrated, and mythologized broadcasts in media history. It wasn’t just a Halloween stunt—it was a seismic moment that redefined the boundaries of storytelling, trust, and technology.

More than eight decades after Orson Welles’ voice crackled across the airwaves, The War of the Worlds remains one of the most studied, celebrated, and mythologized broadcasts in media history. It wasn’t just a Halloween stunt—it was a seismic moment that redefined the boundaries of storytelling, trust, and technology.

A Pop Culture Touchstone

The broadcast has inspired countless adaptations, parodies, and tributes. From films like Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (2005) to episodes of The Simpsons, American Experience, and Doctor Who, the story of Martians invading Earth—and the panic that followed—has become a cultural shorthand for media-induced hysteria.

Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, now hosts a monument commemorating the fictional landing site. Every Halloween, radio stations and museums revisit the broadcast, inviting new generations to experience the thrill, confusion, and brilliance of Welles’ creation.

Even the phrase “War of the Worlds moment” has entered the lexicon, used to describe any media event that blurs the line between fiction and reality.

A Case Study in Media Literacy

In classrooms and lecture halls, the broadcast is dissected as a foundational case in media ethics, audience psychology, and the sociology of mass communication. Scholars explore:

• How format influences perception

• The role of disclaimers and framing

• The psychology of panic and rumor

• The tension between entertainment and responsibility

It’s a reminder that media is not just a mirror—it’s a magnifier. What we hear, how we hear it, and when we hear it can shape our understanding of the world in profound ways.

A Sonic Artifact Worth Preserving

For the USA Radio Museum, The War of the Worlds is more than a historical footnote—it’s a living artifact. The complete original broadcast, preserved in your archives, offers visitors a chance to hear the moment as it unfolded: the rising tension, the breathless bulletins, the eerie silence.

For the USA Radio Museum, The War of the Worlds is more than a historical footnote—it’s a living artifact. The complete original broadcast, preserved in your archives, offers visitors a chance to hear the moment as it unfolded: the rising tension, the breathless bulletins, the eerie silence.

It’s a masterclass in audio storytelling, a testament to the emotional power of sound, and a cornerstone of the museum’s mission to preserve and celebrate radio’s golden age.

By sharing this broadcast, the museum doesn’t just honor Orson Welles—it honors every listener who sat in the dark, gripped by fear and wonder. It honors the medium itself: radio, in all its intimacy, immediacy, and imagination.

Echoes Across Time

In an age of deepfakes, viral misinformation, and algorithmic media, the lessons of 1938 feel more urgent than ever. The War of the Worlds reminds us that technology may change, but human perception remains vulnerable—and that with great storytelling comes great responsibility.

It also reminds us of something simpler, more profound: the joy of being swept away by sound. The thrill of a voice that paints a world. The magic of radio at its most daring.

Archival Spotlight: The Original Broadcast

Before the panic. Before the headlines. Before Orson Welles became a household name—there was the sound.

The USA Radio Museum is proud to present the complete, original 1938 broadcast of The War of the Worlds, preserved in its entirety as a sonic time capsule. This is not a recreation. It is the moment itself: the voices, the silences, the static, the suspense. It is radio at its most daring, most immersive, and most unforgettable.

As you listen, imagine yourself in a living room on Halloween night, 1938. The lights are low. The radio hums. You hear a weather report, then music, then a sudden interruption. A reporter describes strange flashes on Mars. A cylinder crashes into Grovers Mill. The air grows tense. The orchestra fades. The news bulletins escalate. And then—chaos.

This is the broadcast that blurred fiction and reality. That made Americans question what they were hearing. That proved radio could do more than entertain—it could captivate, unsettle, and transform.

We invite you to experience it as it was heard:

• No visuals.

• No spoilers.

• Just sound, imagination, and the thrill of the unknown.

Let the broadcast begin.

_____________________

Columbia Broadcasting System | Orson Welles’ Mercury Theater On The Air | The War Of The Worlds | October 30, 1938

Audio Digitally Enhanced by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

Conclusion: When Sound Became History

On that Halloween eve-night in 1938, Orson Welles didn’t just perform a radio drama—he redefined the medium. With nothing but voices, silence, and imagination, he turned the airwaves into a stage, the nation into his audience, and fiction into fleeting reality. The War of the Worlds was more than a broadcast. It was a moment when sound became history.

The panic it sparked—real or exaggerated—revealed the emotional power of radio. The ethical debates it ignited reshaped broadcasting standards. And the legacy it left behind continues to echo through classrooms, studios, and archives around the world.

For the USA Radio Museum, this broadcast is a cornerstone. It reminds us why we preserve, why we listen, and why we tell these stories. It’s a testament to the magic of audio, the brilliance of Welles, and the enduring thrill of a voice that can make us believe.

As you listen to the original broadcast, preserved in our archives, we invite you to feel what listeners felt that night: wonder, fear, awe. Let it transport you—not just to Grovers Mill, but to a time when radio ruled the imagination.

Because in the end, The War of the Worlds wasn’t about Martians. It was about us—our willingness to believe what was telegraphed through the growing expanse of radio, a medium that, up until that night in 1938, had emanated only responsible voices we trusted—and never thought to pause to ever question.

_____________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.