Car Radio's Cultural Impact Became the Soundtrack of American Life From the moment car radios became accessible to everyday drivers, they trans

Car Radio’s Cultural Impact Became the Soundtrack of American Life

From the moment car radios became accessible to everyday drivers, they transformed the automobile from a mere mode of transportation into a mobile sanctuary of sound. The cultural impact of this shift is profound and multifaceted—touching everything from family dynamics to regional identity, youth rebellion to personal memory.

_____________________

The Birth and Legacy of the Mobile Sound

In the annals of automotive and audio history, few inventions have had the enduring impact of the car radio. It began not as a luxury, but as a lifeline—connecting drivers to the world beyond the windshield. The story of its technological milestones is one of ingenuity, persistence, and cultural transformation, beginning with a bold experiment in 1930 that would forever change how we experience the road.

In the annals of automotive and audio history, few inventions have had the enduring impact of the car radio. It began not as a luxury, but as a lifeline—connecting drivers to the world beyond the windshield. The story of its technological milestones is one of ingenuity, persistence, and cultural transformation, beginning with a bold experiment in 1930 that would forever change how we experience the road.

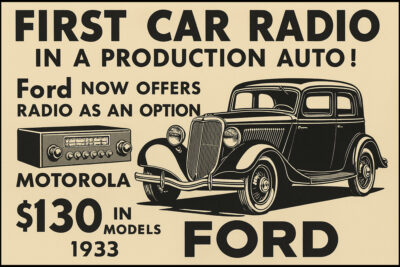

The Motorola 5T71 was more than just a product—it was a statement of possibility. Developed by Paul Galvin and his team at the Galvin Manufacturing Corporation, the 5T71 was the first commercially successful car radio, introduced during the depths of the Great Depression. At a time when most Americans were struggling to afford basic necessities, Galvin saw opportunity in mobility and sound. He recognized that while home radios were becoming common, the automobile remained a silent space. By adapting radio technology for the car, Galvin created a new market—and a new kind of experience.

The technical challenges were formidable. Early radios were bulky, fragile, and prone to interference from the car’s ignition system. Galvin’s engineers had to overcome these hurdles by designing a radio that could withstand vibration, fit within the limited space of a car interior, and deliver clear reception even while the engine was running. The result was the 5T71, a five-tube AM receiver that required a separate battery and antenna system. It wasn’t elegant, but it worked—and it worked well enough to capture the imagination of drivers across the country.

Galvin’s promotional stunt at the 1930 Radio Manufacturers Association Convention in Atlantic City became legendary. Unable to afford a booth inside the hall, he parked his Studebaker outside the venue and blasted music from the 5T71 through loudspeakers. The spectacle drew crowds and orders, proving that the car radio wasn’t just viable—it was desirable. The name “Motorola,” a portmanteau of “motor” and “Victrola,” became synonymous with sound in motion, and the company would eventually adopt it as its own.

From that moment, the car radio began its steady march into the mainstream. By the mid-1930s, push-button tuning and improved circuitry made radios more user-friendly. In 1946, an estimated nine million cars in the U.S. were equipped with radios, and by the 1950s, they were standard in most new vehicles. But the real leap came with the advent of FM reception.

FM radio, introduced into cars in the early 1950s by German manufacturer Blaupunkt, offered superior sound quality and reduced static compared to AM. The Becker Mexico, released in 1953, was a watershed moment—it was the first premium car radio to feature both AM and FM bands, along with an automatic station search function. This marked the beginning of high-fidelity audio in automobiles, and it set the stage for a new era of sonic sophistication.

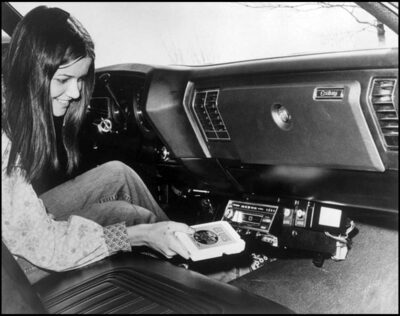

The 1960s and ’70s saw a proliferation of playback formats that further transformed the car radio into a personal jukebox. The introduction of the 8-track tape player, pioneered by William Lear and adopted by Ford in 1965, allowed drivers to listen to their favorite albums on demand. Though bulky and prone to mechanical issues, the 8-track was a revelation—it liberated listeners from the tyranny of radio programming and gave them control over their soundtrack.

Cassette decks soon followed, offering greater portability, longer play times, and the ability to record. By the late 1970s, cassettes had overtaken 8-tracks as the dominant in-car format. The cassette’s compact size and improved fidelity, especially with the advent of Dolby noise reduction and metal tape formulations, made it ideal for automotive use. Drivers could now create mix-tapes, record radio broadcasts, and curate their own musical journeys. The car became not just a place to hear music, but to shape it.

The 1980s and ’90s ushered in the compact disc, which brought digital clarity and instant track access. Pioneer’s CDX-1, introduced in 1984, was the first car CD player, and it quickly gained traction among audiophiles and mainstream consumers alike. Mercedes-Benz was the first automaker to offer a factory-installed CD player in 1985, and by the end of the decade, CD changers and head units were ubiquitous. The CD era represented the peak of physical media in cars—an era of pristine sound and tactile engagement.

But the most transformative milestone came not from a disc or a tape, but from a signal. Bluetooth technology, first introduced in cars in the early 2000s, redefined connectivity. Initially used for hands-free calling, Bluetooth soon enabled wireless music streaming, voice commands, and integration with smartphones. It eliminated the need for physical media and cables, allowing drivers to access vast libraries of music, podcasts, and navigation tools with a tap or a voice prompt.

Bluetooth’s rise coincided with the emergence of infotainment systems—touchscreen interfaces that combined audio, communication, and navigation into a single hub. Apple CarPlay and Android Auto further streamlined the experience, turning the car into an extension of the mobile device. Today, Bluetooth is not just a feature—it’s a foundation. It powers everything from audio playback to vehicle diagnostics, and it continues to evolve with each generation of technology.

From the crackling AM signals of the 1930s to the seamless streaming of the 2020s, the car radio has undergone a remarkable transformation. Each technological milestone—from the Motorola 5T71 to FM stereo, cassette decks, CDs, and Bluetooth—has expanded the possibilities of what a car can be. It’s no longer just a vehicle; it’s a vessel of culture, memory, and connection.

And through it all, the car radio has remained a constant companion—narrating our journeys, amplifying our emotions, and reminding us that even in motion, we are never alone.

Radio as Identity and Territory

By the mid-20th century, the car radio had evolved beyond its mechanical origins to become a vessel of personal and collective identity. It wasn’t just a device—it was a declaration. For millions of Americans, especially teenagers coming of age in the 1950s and ’60s, the car radio offered a sonic canvas on which to paint their values, moods, and aspirations. It turned the automobile into a mobile stage, broadcasting not only music but attitude, defiance, and belonging.

In the postwar years, the rise of youth culture coincided with the proliferation of car ownership. Teenagers, newly empowered by disposable income and a growing sense of autonomy, found in the car radio a tool for self-expression. Cruising became a ritual—windows down, volume up, the dashboard transformed into a pulpit of rebellion. Rock ’n’ roll wasn’t just background noise; it was a manifesto. Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, and Little Richard weren’t merely entertainers—they were co-pilots in a generational revolt.

Motown added another layer to this sonic rebellion. In cities like Detroit, where the car and music industries were deeply intertwined, the car radio became a bridge between assembly lines and soul lines. Teens would tune into stations like WJLB or V98.7, letting the smooth grooves of Marvin Gaye or The Supremes spill into the streets. The music wasn’t just heard—it was felt, shared, and worn like a badge. In this way, the car radio helped define not only personal identity but regional pride.

As the decades progressed, hip-hop emerged as the next great wave of dashboard defiance. In the 1980s and ’90s, young drivers in urban centers blasted Public Enemy, N.W.A., and Tupac from their car stereos, turning every red light into a moment of cultural assertion. The car radio became a megaphone for marginalized voices, a rolling protest against injustice, and a celebration of community resilience. The bass thumped not just in rhythm but in resistance.

But the car radio’s power wasn’t limited to youth rebellion—it also shaped regional flavor in profound ways. Local stations became sonic landmarks, each one a reflection of its community’s tastes, values, and history. A driver in Bakersfield, California might tune into country twang and hear Buck Owens crooning about heartbreak and highways. Meanwhile, someone cruising through New Orleans could catch a brass-heavy jazz set that echoed the city’s vibrant street culture.

In Detroit, the car radio was a mirror of the city’s dual legacy—automotive innovation and musical brilliance. Stations like V98.7 offered smooth jazz that matched the city’s industrial pulse with emotional sophistication. The soundscape of Detroit wasn’t just manufactured—it was curated, lived, and loved. The car radio allowed residents to hear themselves in the music, to recognize their stories in the lyrics, and to feel a sense of place even while in motion.

This regionalism extended beyond genre. Local DJs became cultural icons, their voices as familiar as street signs. They introduced new artists, narrated community events, and offered commentary that reflected the mood of the moment. In many towns, the car radio was the first place people heard about school closings, local tragedies, or neighborhood triumphs. It was a lifeline, a storyteller, and a unifier.

Even the static between stations told a story. It marked the boundaries of broadcast reach, the edges of cultural territory. Crossing state lines meant crossing sonic lines—what played in one region might be absent in another. This gave the car radio a sense of adventure and discovery. Drivers learned to associate certain sounds with certain places, creating a mental map of America defined not by geography but by genre.

In this way, the car radio became both a passport and a flag. It allowed people to explore new cultures while affirming their own. It gave teenagers a voice, communities a soundtrack, and the nation a chorus of diversity. Whether through rebellion or regionalism, the car radio helped Americans define who they were, where they belonged, and how they wanted to be heard.

Emotional Resonance and Memory

There’s a kind of magic that happens when music meets motion. The car radio, more than any other medium, has the uncanny ability to turn ordinary drives into unforgettable moments. It’s not just about sound—it’s about memory, emotion, and the way a song can become forever tied to a stretch of highway, a season of life, or a single, fleeting feeling.

Everyone remembers their first “song moment” behind the wheel. Maybe it was a breakup anthem that hit harder than expected, echoing through the cabin as tears blurred the dashboard lights. Or maybe it was a summer hit, blasting through open windows as the wind tangled hair and laughter spilled into the air. For some, it was a gospel tune on a quiet Sunday morning, the voice of Mahalia Jackson or Kirk Franklin rising like prayer through the static. These moments weren’t planned—they were discovered. And once they happened, they became permanent fixtures in the architecture of memory.

The car radio made these moments possible because it was unpredictable. Unlike curated playlists or algorithmic suggestions, radio offered serendipity. You didn’t know what was coming next, and that was part of the thrill. A song could arrive like a gift, perfectly timed to your mood or your surroundings. It could be the track you hadn’t heard in years, the one that reminded you of someone you used to love, or the one that made you feel like everything was going to be okay. And because you were driving—alone or with someone—the music had space to breathe. It filled the car, wrapped around you, and became part of the journey.

Before streaming and satellite, tuning the radio was a ritual. It required patience, curiosity, and a willingness to explore. Drivers would twist the dial slowly, listening for the faint signal of a distant station. The static between frequencies wasn’t just noise—it was possibility. Somewhere in that haze might be a late-night jazz show from Chicago, a country ballad from Nashville, or a pirate broadcast from a college dorm. The act of tuning in was tactile and intimate. It connected you to the world in real time, and it made every drive feel like a search for something just out of reach.

Countdown shows added another layer of anticipation. Whether it was Casey Kasem’s “American Top 40” or a local DJ’s weekend roundup, these broadcasts created communal listening experiences. You weren’t just hearing the hits—you were part of a national moment. You knew that thousands of other drivers were listening to the same songs, at the same time, across different cities and states. It was a shared soundtrack, stitched together by radio waves and roadways.

And then there were the rare broadcasts—the ones you stumbled upon late at night or during long drives through unfamiliar terrain. A forgotten Motown B-side. A live concert recording. A DJ spinning vinyl with reverence and grit. These moments felt like secrets, like treasures unearthed by chance. They reminded you that radio wasn’t just a medium—it was a living archive, a place where history and emotion collided.

The emotional resonance of car radio is also tied to its intimacy. Unlike home stereos or public speakers, the car radio speaks directly to the driver. It’s a one-on-one conversation, a voice in the dark, a melody that moves with you. It’s there when you’re celebrating, grieving, dreaming. It’s there when you’re running away or coming home. And because it’s woven into the act of driving—a deeply personal and often reflective experience—it becomes a mirror for your inner world.

Even today, with all the advances in audio technology, there’s something irreplaceable about the car radio’s emotional pull. It’s not just nostalgia—it’s a testament to the power of sound to shape memory. The songs we hear in cars don’t just play—they imprint. They become part of our story, etched into the rhythm of tires on pavement and the hum of engines beneath us.

Democratizing Access to Sound

In the early decades of the 20th century, the car was a symbol of mobility, freedom, and status—but it was silent. The hum of the engine and the crunch of tires on gravel were the only soundtrack to the American road. Radio, meanwhile, was transforming domestic life, bringing music, news, and drama into living rooms across the country. But it wasn’t until the 1930s that these two technologies began to converge in a meaningful way. And when they did, the result was revolutionary.

At first, car radios were a luxury—expensive, temperamental, and reserved for the privileged few. In 1930, only about 40% of cars had radios, and those that did required bulky vacuum tubes, separate batteries, and external antennas. The cost of installation could rival a month’s wages, and the technology was still in its infancy. But even then, the allure was undeniable. To hear Bing Crosby croon or Franklin D. Roosevelt deliver a fireside chat while cruising down a country road was to experience something new: culture in motion.

As the technology improved and prices dropped, car radios began to spread. By the 1940s, wartime innovations had made radios smaller, more reliable, and easier to install. The transistor, introduced in 1947, was a game-changer—lighter, cheaper, and more durable than vacuum tubes. Suddenly, car radios weren’t just for the elite. They were for the factory worker, the traveling salesman, the young couple on their honeymoon. Sound was no longer tethered to the home—it was on the move.

By the 1970s, the transformation was complete. Over 90% of American cars came equipped with radios, and what had once been a luxury was now a standard feature. This shift wasn’t just technological—it was cultural. It meant that millions of people, regardless of income or geography, could access music, news, sports, and sermons while on the road. The car radio became a great equalizer, offering a shared experience across class lines and state borders.

But the democratization of sound went beyond access—it reshaped the very nature of culture itself. Car radios made culture portable. They turned the car into a vessel of personal expression, a rolling theater, a mobile newsroom. Drivers could tune into local stations and hear voices that reflected their community, or switch to national broadcasts and feel connected to a larger narrative. The boundaries between public and private space began to blur. A sermon heard in solitude on a Sunday drive could be as powerful as one heard in a crowded pew. A baseball game broadcast on AM radio could unite listeners across hundreds of miles, each cheering from their own dashboard.

This portability also changed how people consumed music. Before the car radio, music was largely a communal experience—heard in concert halls, dance clubs, or around the family phonograph. The car radio made music personal. It allowed listeners to sing along, cry, reflect, or rejoice in solitude. It gave birth to the phenomenon of the “driving song”—tracks that felt tailor-made for the open road, for the rhythm of tires on pavement and the sweep of passing scenery. Artists began to write with this in mind, crafting songs that resonated with the intimacy and introspection of the driving experience.

Moreover, the car radio expanded the reach of regional sounds. A driver in Memphis could discover Chicago blues. A commuter in New Jersey might stumble upon a gospel station from Georgia. This cross-pollination of genres helped shape the American musical landscape, breaking down barriers and introducing listeners to styles they might never have encountered otherwise. It was a quiet revolution—one dial turn at a time.

And let’s not forget the role of the DJ. These voices became trusted companions, curators of taste, and narrators of the day’s events. In the cocoon of the car, their words carried weight. They offered comfort during long drives, excitement during traffic jams, and a sense of continuity in a rapidly changing world. The intimacy of radio was amplified by the solitude of driving, creating a bond between broadcaster and listener that was deeply personal.

In this way, the car radio didn’t just democratize access to sound—it democratized access to emotion, to identity, to belonging. It allowed people to carry their culture with them, to shape their own sonic environment, and to find connection in motion. It turned the car into a sanctuary, a stage, a confessional. And it did so quietly, steadily, until it became an inseparable part of the American experience.

For the USA Radio Museum, this story is more than a technical evolution—it’s a testament to the power of sound to unite, to inspire, and to transform.

The Status of AM/FM Radio Today

AM and FM radio remain foundational pillars of broadcast media, but their dominance has waned in the face of streaming, satellite, and infotainment systems. FM still leads in music and local programming, while AM has carved out a niche in talk radio, sports, religious broadcasts, and emergency alerts. According to Nielsen, over 82 million Americans still tune in to AM radio monthly, especially in rural areas where it remains a lifeline during extreme weather and natural disasters.

However, AM radio is facing existential challenges. Electric vehicles from brands like BMW, Mazda, and Volkswagen have begun phasing out AM receivers, citing interference from electric motors. This has sparked pushback from broadcasters and lawmakers, with campaigns like “Depend on AM Radio” urging automakers to preserve the medium for public safety and cultural continuity. Ford, notably, reversed its decision and pledged to include AM in all 2024 models.

FM radio, while more stable, is also contending with competition from streaming services and satellite radio. It still offers local flavor and immediacy, but younger audiences increasingly favor on-demand content.

SiriusXM: The New Standard

SiriusXM has become the de facto premium audio option in new vehicles. Most automakers now include a 3- to 6-month free trial of SiriusXM with new cars, and the service is integrated into nearly 100 million vehicles across North America. It offers over 130 channels of music, talk, sports, and news, many of which are exclusive or ad-free depending on the subscription tier.

In 2025, SiriusXM launched SiriusXM Play, a new ad-supported, low-cost subscription tier priced under $7/month. This move aims to attract price-sensitive listeners and compete with streaming giants like Spotify and Apple Music. It also marks a shift in strategy—SiriusXM is now embracing advertising in its music channels, something it previously avoided.

Gone are the days of physical media in cars. No more ejecting tapes or flipping discs. Instead, we have Bluetooth streaming, voice-activated playlists, and satellite-curated channels that follow us from driveway to highway.

Final Thoughts: How the Automobile Saved Radio

As the digital age redefined how we consume media—streaming platforms, podcasts, and algorithm-driven playlists—traditional radio faced an existential reckoning. Home stereo systems with built-in AM/FM tuners became rarities. Portable radios, once ubiquitous, faded from store shelves. Even boomboxes and clock radios, once staples of everyday life, gave way to smart speakers and mobile apps. Yet through all this upheaval, one place remained steadfast: the car.

The automobile didn’t just preserve radio—it gave it purpose, intimacy, and endurance. In fact, it may be the last great bastion of broadcast radio in America. For millions of drivers, the car is still where radio lives. It’s where we tune in to morning shows, traffic updates, sports commentary, and music that moves us. It’s where local stations still matter, where DJs still speak directly to their communities, and where AM/FM still holds emotional and practical relevance.

This wasn’t always guaranteed. In the 1930s, car radios were a luxury. By the mid-1960s, AM/FM units began appearing as optional features in U.S. automobiles—especially in models from Buick, Chrysler, and Ford. The rise of FM stereo in the late ’60s and early ’70s, coupled with the growing popularity of music formats like progressive rock and jazz, helped cement FM’s place in the dashboard. By the 1980s, AM/FM radios had become standard equipment in most vehicles, no longer a premium add-on but a cultural necessity.

This shift wasn’t just about convenience—it was about survival. As home radio sales plateaued and then declined, car radios surged. In 1965 alone, over 460,000 auto FM tuners were sold, with forecasts predicting 900,000 units by 1966. The car became the primary venue for radio listening, and that trend has only intensified. Today, even as infotainment systems evolve and satellite radio like SiriusXM becomes standard in new vehicles, AM/FM remains embedded in the driving experience.

And it’s not just about technology—it’s about emotion. The car radio is where we hear breaking news, discover new artists, and feel less alone on long drives. It’s where we connect with our cities, our memories, and our moods. It’s where radio continues to thrive—not as a relic, but as a companion.

So yes, one could actually surmise: cars saved the radio. They gave it wheels, voice, and longevity. And in doing so, they preserved one of the most intimate and democratic forms of media we’ve come to accept, embrace and seemingly, forever have known . . . a form of connection we’ve relied on with every turn of the key, twist of the dial, and stretch of the road.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view.