Curator’s Note — Pop’s Unsung Poet: Celebrating Bobby Hart’s Musical Legacy Bobby Hart’s melodies didn’t just top charts—they became the emotional

Curator’s Note —

Pop’s Unsung Poet: Celebrating Bobby Hart’s Musical Legacy

Bobby Hart’s melodies didn’t just top charts—they became the emotional soundtrack of a generation. As one half of the legendary duo Boyce & Hart, his songs gave voice to the joy, longing, and rhythm of the 1960s, shaping the sound of the Monkees and echoing across decades of pop culture. In this museum-exclusive tribute, we honor Hart not only as a hitmaker, but as a steward of feeling—a songwriter whose work still plays in stereo through every radio dial, playlist, and memory. His legacy is more than music. It’s the heartbeat of youth, preserved in every lyric and every listener who still hums along. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Bobby Hart (1939–2025): The Architect of Bubblegum Dreams and Monkee Magic

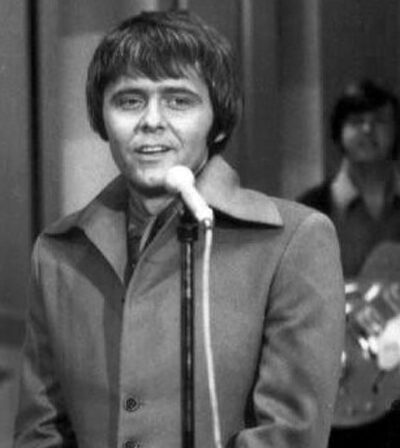

Bobby Hart, the songwriter, producer, and pop visionary whose melodies helped define a generation, passed away at his Los Angeles home on September 14, 2025. He was 86. With Tommy Boyce, his creative counterpart and kindred spirit, Hart co-wrote the soundtrack to the Monkees’ meteoric rise—and in doing so, etched his name into the DNA of American pop culture.

Born Robert Luke Harshman in Phoenix, Hart was the son of a minister and a self-described shy kid with a “strong desire to distinguish” himself. Music became his compass. By high school, he had mastered piano, guitar, and the Hammond B-3 organ, even building his own amateur radio station—a prophetic nod to the sonic legacy he would leave behind.

Enter Tommy Boyce: A Partnership in Pop

Bobby Hart’s creative destiny crystallized in 1959 when he met Tommy Boyce, a fellow dreamer and songwriter from Charlottesville, Virginia. Boyce had already shown remarkable tenacity—famously waiting six hours outside Fats Domino’s hotel room to pitch a song called “Be My Guest.” That track became a million-seller and launched Boyce’s career as a hitmaker. Hart, meanwhile, had just adopted the stage name Bobby Hart (shortened from Harshman) and was navigating the Los Angeles music scene with quiet determination and a growing arsenal of musical skills.

Their first collaboration, “Girl in the Window,” didn’t chart, but it marked the beginning of a creative bond that would soon reshape pop music. Boyce played guitar on the track, and the two quickly discovered a shared sensibility: melodic instinct, lyrical wit, and a love for crafting songs that felt both immediate and timeless.

By 1964, Boyce & Hart had begun to make waves as a songwriting duo. Their breakthrough came with “Lazy Elsie Molly,” recorded by Chubby Checker, followed by “Come a Little Bit Closer” for Jay and the Americans—a Top 10 hit that blended cinematic storytelling with irresistible hooks. They also penned “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone” for Paul Revere & the Raiders and “Words” for the Leaves, both of which would later become Monkees B-sides. Their versatility was evident: they could write for garage rockers, crooners, and TV stars alike.

It was this versatility that caught the attention of Don Kirshner, the music impresario behind Screen Gems and the Brill Building’s hit-making machinery. In late 1965, Kirshner was assembling a songwriting factory to fuel a new made-for-TV band modeled on the Beatles—a quartet of actors who would become known as the Monkees. Kirshner needed songs that were catchy, youthful, and radio-ready. Boyce & Hart were the perfect fit.

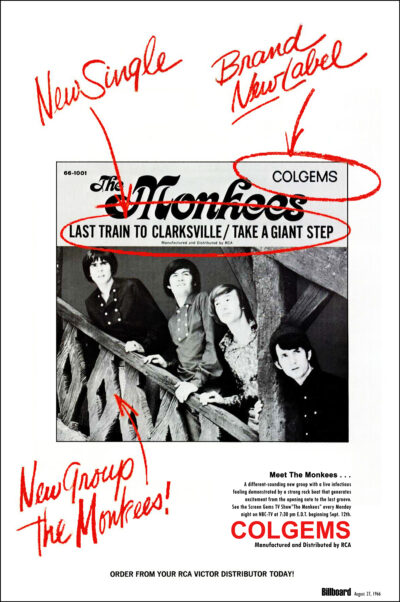

They were tapped to write, produce, and perform the soundtrack for the Monkees’ pilot episode—including singing lead vocals on the demo tracks before the show was even cast. Their twangy guitar riff for “Last Train to Clarksville,” inspired by the Beatles’ “Paperback Writer,” became the Monkees’ first No. 1 hit. Their theme song, with its iconic “Hey, hey, we’re the Monkees” chant, was born from a spontaneous sidewalk jam session. As Hart recalled in Psychedelic Bubblegum, “We had created the perfect recipe for inspiration and started singing about just what we were doing: ‘Walkin’ down the street.’”

Boyce & Hart weren’t just writing songs—they were crafting a sonic identity. They produced six tracks on the Monkees’ debut album, used their own band (the Candy Store Prophets) as session players, and helped define the “Monkee sound” that blended British Invasion energy with American pop charm. Their work laid the foundation for one of the most successful multimedia acts of the 1960s.

Boyce & Hart had become more than songwriters. They were sonic architects, cultural curators, and emotional translators for a generation coming of age in the glow of television and transistor radios.

“Hey, Hey, We’re the Monkees”

When Don Kirshner tapped Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart to write music for a new made-for-TV band in late 1965, he wasn’t just hiring songwriters—he was commissioning sonic architects. The Monkees were conceived as a television phenomenon first, a band second. But thanks to Boyce & Hart, they became both.

Tasked with crafting music for a fictional quartet modeled loosely on the Beatles, Boyce & Hart delivered more than catchy tunes—they delivered a fully formed sound. Their first major contribution, “Last Train to Clarksville,” was a masterclass in pop construction. The song’s title referenced Clarksville, Tennessee—home to a military base—and its lyrics hinted at a soldier’s farewell. Released in August 1966, it became the Monkees’ first No. 1 hit, even before the show aired.

Tasked with crafting music for a fictional quartet modeled loosely on the Beatles, Boyce & Hart delivered more than catchy tunes—they delivered a fully formed sound. Their first major contribution, “Last Train to Clarksville,” was a masterclass in pop construction. The song’s title referenced Clarksville, Tennessee—home to a military base—and its lyrics hinted at a soldier’s farewell. Released in August 1966, it became the Monkees’ first No. 1 hit, even before the show aired.

But their most iconic creation was the Monkees’ theme song. As Hart recalled in Psychedelic Bubblegum, the moment of inspiration came during a casual walk. “Boyce began strumming his guitar and I joined in by snapping my fingers & making noises with my mouth that simulated an open & closed hi-hat cymbal,” he wrote. “We had created the perfect recipe for inspiration and started singing about just what we were doing: ‘Walkin’ down the street.’” That spontaneous jam became the opening line of the Monkees’ theme—“Here we come, walkin’ down the street”—and the unforgettable chant, “Hey, hey, we’re the Monkees.”

Boyce & Hart didn’t just write the songs—they shaped the Monkees’ musical identity. They produced six tracks on the band’s self-titled debut album, including “Let’s Dance On,” “Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day,” and “I Wanna Be Free,” a tender ballad that revealed Hart’s emotional depth as a lyricist. Their own band, the Candy Store Prophets, served as the session musicians, laying down the instrumental tracks that the Monkees would later sing over. In fact, before the Monkees were even cast, Boyce & Hart recorded the pilot’s soundtrack themselves, singing lead vocals on the demos.

Their production style blended British Invasion energy with American pop sensibility—jangly guitars, tight harmonies, and buoyant rhythms. It was bubblegum pop with bite, and it resonated instantly with young audiences. The Monkees’ debut album went multi-platinum, and their sound became a cultural phenomenon.

Micky Dolenz, the Monkees’ drummer and lead vocalist on many of their hits, later credited Boyce & Hart with being “instrumental in creating the unique ‘Monkee’ sound we all know and love.” Their influence extended beyond the studio. They helped the Monkees transition from a scripted TV act into a legitimate chart-topping band, laying the groundwork for the group’s eventual fight for creative control.

Boyce & Hart’s work on the Monkees wasn’t just commercially successful—it was artistically foundational. They gave the band its voice, its rhythm, and its emotional core. And in doing so, they gave a generation its soundtrack.

The Last Train to Cultural Immortality

Hart’s partnership with Tommy Boyce was lightning in a bottle. Together, they penned “Last Train to Clarksville,” “I’m Not Your Steppin’ Stone,” and the Monkees’ iconic theme song—tracks that weren’t just hits, but cultural touchstones. Their work on the Monkees’ debut album, which featured six Boyce & Hart compositions and their own backing band, the Candy Store Prophets, helped shape the “Monkee sound” that Micky Dolenz later credited as “instrumental” to the group’s success.

Their songwriting wasn’t confined to bubblegum pop. “I Wanna Be Free” revealed a tender melancholy, while their theme for Days of Our Lives showed their versatility. Covered by artists as varied as Dean Martin and the Sex Pistols, Boyce & Hart’s catalog was a bridge between eras, genres, and sensibilities.

Pop Culture Polymaths

Boyce & Hart weren’t just musicians—they were multimedia personalities whose creative reach extended far beyond the recording studio. At the height of their fame in the late 1960s, they became fixtures of American television, appearing on popular sitcoms like I Dream of Jeannie, Bewitched, and The Flying Nun. Their on-screen charm mirrored the buoyancy of their music, and their cameos helped blur the line between pop stars and TV personalities—an early example of cross-platform celebrity that would become standard in decades to follow.

Their cultural engagement wasn’t limited to entertainment. In 1968, amid a turbulent political climate, Boyce & Hart lent their voices to a cause that resonated with their youthful fanbase: lowering the voting age. They actively campaigned for Senator Robert F. Kennedy and wrote the anthem “L.U.V. (Let Us Vote)” to support the 26th Amendment, which ultimately passed in 1971. The song was more than a catchy slogan—it was a rallying cry for civic engagement, blending bubblegum pop with political purpose. Their advocacy reflected a belief that music could be both fun and meaningful, and that artists had a role to play in shaping the future.

Their songwriting catalog proved remarkably versatile. While they were best known for crafting hits for the Monkees, their songs were covered by a wide range of artists across genres and generations. Dean Martin recorded their material, adding a crooner’s polish to their pop sensibility. On the other end of the spectrum, the Sex Pistols famously covered “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone,” transforming a Boyce & Hart B-side into a punk anthem. That unlikely lineage—from bubblegum to rebellion—underscored the duo’s uncanny ability to write songs that transcended style and era.

Perhaps most surprising was their contribution to daytime television. Alongside Charles Albertine, Boyce & Hart co-wrote the theme for Days of Our Lives, the long-running NBC soap opera that became a staple of American households. The theme’s gentle piano melody and emotional undertones stood in contrast to their pop hits, showcasing their range as composers. It was a quiet triumph—one that played daily for millions of viewers, embedding their music into the fabric of everyday life.

Their presence on television, in politics, and across musical genres made Boyce & Hart true pop culture polymaths. They weren’t just riding the wave of the 1960s—they were helping shape it. Whether through a sitcom cameo, a campaign anthem, or a soap opera theme, their work reflected a deep understanding of the emotional rhythms that connected people to sound, story, and each other.

_____________________

A ‘Boyce & Hart’ Sidebar: Artists in Their Own Right

As the Monkees gained creative control and moved toward self-production, Boyce & Hart stepped into the spotlight themselves. In 1967, they signed with Herb Alpert’s A&M Records—a label known for its artist-friendly ethos and pop innovation. Their debut single under A&M, “Out And About,” peaked #39 in 1967. But it was their third single, “I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonite,” that became a Top 10 hit in early 1968, showcasing their melodic charm and lyrical wit. That same year, they performed the song on The Hollywood Palace, hosted by Alpert himself—a moment that symbolized their transition from behind-the-scenes hitmakers to front-and-center pop personalities.

Their follow-up singles, including “Alice Long (You’re Still My Favorite Girlfriend)” and “Goodbye Baby (I Don’t Want to See You Cry),” both cracked the Top 40, affirming their appeal beyond the Monkees’ orbit. Their albums ‘Test Patterns’ and ‘I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonite’ were quintessential bubblegum pop—bright, brassy, and irresistibly melodic. But beneath the surface was a songwriting sophistication that belied the genre’s reputation. Hart and Boyce knew how to craft hooks, yes—but they also knew how to tap into emotional nuance, as evidenced by the bittersweet “I Wanna Be Free.”

_____________________

Beyond the Bubblegum

As the 1960s gave way to new musical landscapes, Bobby Hart continued to evolve—proving that his talents extended far beyond the bubblegum pop he helped pioneer. In the 1970s and ’80s, Hart embraced new genres, new collaborators, and new audiences, all while staying true to his gift for crafting emotionally resonant songs.

One of his most acclaimed works from this era was “Over You,” co-written with Austin Roberts and performed by Betty Buckley for the 1983 film Tender Mercies. The song, a haunting ballad of heartbreak and resilience, earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song. Set against the backdrop of a quiet country drama starring Robert Duvall, “Over You” showcased Hart’s ability to write with cinematic depth and lyrical grace. It was a far cry from the Monkees’ playful charm—but no less powerful. The nomination marked a career milestone, affirming Hart’s place among the great American songwriters.

Hart’s versatility was further demonstrated in the mid-1980s when he co-wrote “My Secret (Didja Gitit Yet?)” for New Edition, alongside Dick Eastman. The track, featured on the group’s All for Love album, blended R&B grooves with youthful swagger, proving that Hart could adapt to the sound of a new generation without losing his melodic touch. Hart’s post-Boyce career was equally rich. He co-wrote “Hurt So Bad,” a hit for Little Anthony and the Imperials later revived by Linda Ronstadt. His ability to write across genres—from pop to soul to country—was a testament to his enduring relevance and creative curiosity.

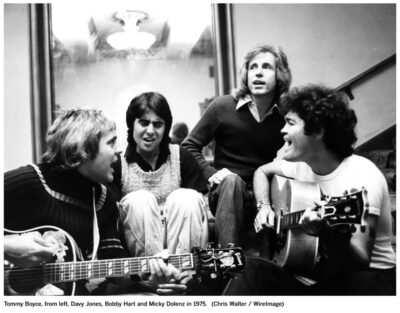

In the mid-1970s, Hart reunited with Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones—two original members of the Monkees—for a new musical venture: Dolenz, Jones, Boyce & Hart. The group released a self-titled album in 1976 and embarked on a national tour, performing a mix of Monkees classics, Boyce & Hart hits, and new material. Though the album didn’t chart significantly, the tour was a nostalgic success, drawing fans eager to reconnect with the sound that had defined their youth. The collaboration was more than a reunion—it was a celebration of shared history, creative camaraderie, and the enduring power of pop.

The Monkees’ resurgence in the 1980s, fueled by MTV reruns and renewed fan interest, brought fresh attention to Boyce & Hart’s foundational role in the band’s success. Hart embraced the moment, participating in interviews, retrospectives, and fan events that honored the legacy he helped build.

In 2014, the documentary The Guys Who Wrote ’Em finally gave Boyce & Hart their long-overdue spotlight. Directed with warmth and wit, the film chronicled their journey from Brill Building hopefuls to pop culture icons, featuring interviews, archival footage, and heartfelt tributes from peers and fans. It was a celebration not just of their hits, but of their humanity—the friendship, the struggles, and the joy that fueled their music.

Hart’s creative journey didn’t stop there. In later years, he explored spiritual themes, publishing a book on Kriya Yoga and the teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda. His final works reflected a man who had not only written songs that moved millions, but who had also sought meaning beyond the spotlight.

From Oscar nods to R&B grooves, from reunion tours to spiritual reflection, Bobby Hart’s post-Monkees career was a testament to artistic resilience. He never stopped writing, never stopped evolving, and never stopped believing in the power of music to connect, heal, and inspire.

The Tragedy of Tommy Boyce

Tommy Boyce’s death by suicide on November 23, 1994, at the age of 55, cast a long and sobering shadow over one of pop music’s most joyful legacies. Known to millions as the upbeat, charismatic half of Boyce & Hart, Tommy was a prolific hitmaker whose songs defined the sound of the 1960s. But behind the cheerful tunes and television smiles was a man quietly battling personal demons—struggles that remained largely invisible to the public until his tragic passing.

Born Sidney Thomas Boyce in Charlottesville, Virginia, Tommy was a musical prodigy with a fearless streak. His first big break came in 1959 when he famously waited outside Fats Domino’s hotel room for hours to pitch a song. That song, “Be My Guest,” became a Top 10 hit and launched Boyce’s career as a songwriter. He was bold, spontaneous, and relentlessly creative—a perfect counterbalance to Bobby Hart’s introspective precision. Together, they formed a partnership that was as emotionally rich as it was musically fruitful.

Throughout the 1960s, Boyce & Hart rode a wave of success that few could imagine. They wrote and produced hits for the Monkees, released their own charting singles, and became fixtures on television and radio. But fame, as always, came with its own pressures. The demands of constant output, the shifting tides of musical taste, and the personal toll of life in the spotlight began to weigh heavily on Boyce.

In the years following their peak, Boyce faced a series of challenges—both professional and personal. He struggled with depression and declining health, including complications from a brain aneurysm that affected his well-being and creative output. Despite occasional reunions and collaborative projects, including the Dolenz, Jones, Boyce & Hart tour in the 1970s, Boyce’s inner battles persisted. Friends and colleagues noted that he remained generous and warm, but increasingly withdrawn.

His death in 1994 was a heartbreak felt deeply by Bobby Hart, who had shared not only a career but a profound friendship with Boyce. In interviews and in his memoir Psychedelic Bubblegum, Hart spoke candidly about the pain of losing his creative soulmate. “Tommy was the spark,” Hart once said. “He brought joy into every room, and into every song. Losing him was like losing a part of myself.”

The tragedy of Tommy Boyce reminds us that even the brightest harmonies can carry shadows. It’s a sobering truth in the world of pop music—that behind the glittering melodies and smiling faces, there can be silent suffering. Honoring Boyce’s legacy means embracing the full human story: the joy he gave, the pain he carried, and the enduring beauty of the music he left behind.

Today, his songs still play on the radio, in playlists, and in the hearts of those who grew up with them. And with every snap of the fingers and every walk down the street, we remember Tommy Boyce—not just as a hitmaker, but as a deeply human artist whose life and loss continue to resonate.

A Legacy Etched in Stereo

To listen to Boyce & Hart is to hear the heartbeat of a generation—bright, buoyant, and brimming with possibility. Their songs weren’t just background music; they were emotional landmarks. From the opening riff of “Last Train to Clarksville” to the wistful ache of “I Wanna Be Free,” their melodies captured the optimism of the 1960s, the charm of television-era pop, and the emotional undercurrents that made bubblegum music far more than a guilty pleasure. Bobby Hart didn’t just write hits—he helped shape the emotional architecture of youth culture. His melodies were memory machines, his lyrics a bridge between innocence and introspection.

Their music was everywhere—on transistor radios tucked under pillows, on turntables spinning in teenage bedrooms, and on television screens that brought the Monkees into millions of homes. Boyce & Hart’s songs were the soundtrack to first crushes, summer road trips, and the kind of wide-eyed wonder that defined coming of age in the postwar boom. They gave voice to a generation that was learning to dance, dream, and define itself.

But legacy is never one note. Tommy Boyce’s tragic passing in 1994 reminds us that even the brightest harmonies can carry shadows. Behind the cheerful tunes was a duo whose friendship, creativity, and vulnerability gave their music its soul. Boyce, the extroverted spark, and Hart, the introspective craftsman, balanced each other in ways that made their partnership magnetic. Their bond was more than professional—it was personal, profound, and deeply human.

Boyce’s death by suicide at age 55 was a heartbreak that reverberated through the music community. It exposed the quiet toll of fame, the emotional weight of creative pressure, and the fragility that can exist behind even the most joyful art. For Bobby Hart, the loss was devastating. In interviews and in his memoir Psychedelic Bubblegum, Hart spoke candidly about the pain of losing his closest collaborator—a man who had been his creative mirror and his brother in song.

Honoring Bobby Hart means honoring that full story—the joy, the ache, and the enduring echo. It means recognizing that their music was born not just of talent, but of trust, vulnerability, and a shared belief in the power of pop to connect hearts across airwaves and eras.

The last train may have left the station, but its whistle still echoes in the hearts of a generation who lived its rhythm. For those who came of age in the 1960s, Boyce & Hart’s songs weren’t just catchy—they were the soundtrack to the best years of our lives. Their melodies carried our hopes, their lyrics mirrored our youth, and their spirit remains etched in every memory that awakens whenever their songs play on the radio—today, tomorrow, and always.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.