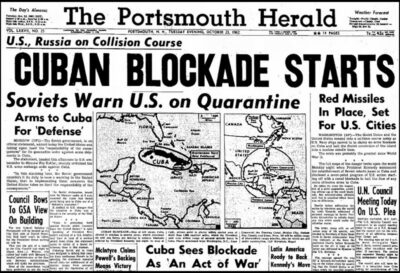

When The World Held Its Collective Breath: October 23, 1962 An Introduction for this news-worthy, and historic, USA Radio Museum Feature On

When The World Held Its Collective Breath: October 23, 1962

An Introduction for this news-worthy, and historic, USA Radio Museum Feature

A photograph of a ballistic missile base in Cuba, used as evidence with which U.S. President John F. Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis, on October 24, 1962. (Credit: The Atlantic)

On the evening of October 23, 1962, Americans huddled around their radios with a sense of unease that hadn’t been felt since Pearl Harbor. The voice of NBC crackled through living rooms and kitchens, delivering urgent dispatches from Washington, Moscow, and the Caribbean Sea. The words were measured, but the stakes were not: the United States had just enacted a naval quarantine of Cuba, and Soviet ships—some possibly carrying nuclear warheads—were steaming toward the line.

This was not fiction. This was not rehearsal. This was the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the world was teetering on the edge of nuclear war.

Today, 63 years later, the USA Radio Museum invites you to relive that moment through the lens of sound. Our featured archival broadcast—a 24-minute NBC Radio Report from October 23, 1962—captures the tension, the diplomacy, and the dread that defined that day. But to fully understand the weight of what Americans were hearing that night, we must first trace the path that led the nation and the world to witness those 13 harrowing days in October 1962. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Prelude to the Brink: A Timeline of Escalation

August–September 1962: The Build-Up

• Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev secretly deploys nuclear missiles to Cuba, aiming to counter U.S. missiles in Turkey and protect the fledgling Castro regime.

• U.S. intelligence begins detecting unusual Soviet activity on the island—military convoys, construction sites, and long-range missile components.

October 14, 1962: The Discovery

• A U-2 reconnaissance flight over Cuba captures photographic evidence of Soviet medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) sites under construction.

• The images are rushed to Washington, where CIA analysts confirm the presence of offensive nuclear weapons.

October 16–21: The ExComm Convenes

• President John F. Kennedy assembles the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (ExComm) to debate options: airstrikes, invasion, or a naval blockade.

• The group meets in secret, weighing the risks of escalation against the need to act decisively.

October 22, 1962: The Televised Address

• At 7:00 p.m. EST, Kennedy addresses the nation:

• He announces a naval “quarantine” of Cuba to prevent further delivery of offensive weapons.

October 23, 1962: The Quarantine Begins

• Kennedy signs Proclamation 3504, authorizing the U.S. Navy to intercept and inspect Soviet ships approaching Cuba.

• The Organization of American States (OAS) endorses the action, lending hemispheric legitimacy.

• Soviet ships continue toward the quarantine line. The world watches—and waits.

This is the moment captured in our featured NBC Radio Report. You’ll hear the voices of correspondents reporting from the Pentagon, the United Nations, and the streets of Washington. You’ll hear the tension in their tone, the uncertainty in their words, and the gravity of a world on the edge.

As you listen, remember: this was not just a political crisis. It was a human one. Families made evacuation plans. Schoolchildren practiced duck-and-cover drills. Broadcasters, like those at NBC radio, became the nation’s lifeline—narrating history as it happened, minute by minute.

Let this NBC Radio broadcast serve not only as a historical document, but as a tribute to the power of radio in times of peril. In 1962, it was the voice in the dark. Today, it is the echo of a world that came perilously close to existential silence.

_____________________

NBC Radio Special Report | Blockade Over Cuba | October 23, 1962

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

Special Audio Source Acknowledgment

This recording is presented courtesy of the exceptional Past Daily website and is the property of its founder and curator, Gordon Skene, whose remarkable archive continues to preserve and share historic audio of lasting cultural significance. The featured broadcast—like many in Past Daily’s vast collection—was made freely available for streaming play and downloading in the earlier years of the site. During that period, the author acquired numerous historic recordings from Past Daily, several of which have been respectfully featured on the (former) Motor City Radio Flashbacks website over the years—to the site’s (and the owner’s) sole credit. Founded in 2012, Past Daily remains active and thriving online, dedicated to preserving and presenting audio history to a global audience. To support their ongoing mission and explore more of their archival treasures, please visit Past Daily—or simply click HERE.

_____________________

Proclamation 3504: Interdiction of the Delivery of Offensive Weapons to Cuba

Signed by President John F. Kennedy after 7:00 p.m. on October 23, 1962

As the sun set over Washington on October 23, 1962, President John F. Kennedy signed a document that would become the legal and moral cornerstone of America’s response to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Proclamation 3504, titled Interdiction of the Delivery of Offensive Weapons to Cuba, formally authorized the United States Navy to establish a quarantine around the island of Cuba. This was not a declaration of war, nor was it labeled a “blockade”—a term that carried dangerous legal implications under international law. Instead, Kennedy chose the word “quarantine,” a strategic linguistic pivot that signaled defensive intent while asserting firm control.

President John F. Kennedy signs a proclamation enacting the U.S. arms quarantine against Cuba, on October 23, 1962. (Credit: The Atlantic)

The proclamation was grounded in the Joint Resolution of Congress, passed on October 3, 1962, which empowered the President to act against the expansion of Soviet military power in the Western Hemisphere. With this authority, Kennedy declared that the peace and security of the United States and the Americas were directly threatened by the installation of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. The document ordered the Secretary of Defense to enforce the quarantine, giving U.S. forces the right to intercept and inspect any vessel suspected of carrying offensive weapons toward the island.

What made Proclamation 3504 so significant was not just its content, but its timing and tone. It marked the transition from covert intelligence gathering to overt military enforcement. It was a public signal to both allies and adversaries that the United States would not tolerate the presence of nuclear weapons so close to its shores—but it would act with restraint, legality, and clarity.

By framing the action as a defensive measure, Kennedy preserved the possibility of diplomacy. The quarantine bought time—time for negotiations, time for back-channel communications, and time for the world to step back from the brink. It was a calculated move that balanced constitutional authority with international caution, and it remains a defining example of presidential leadership under pressure.

For the USA Radio Museum’s October 23 feature, this proclamation stands as a powerful artifact of resolve. It is the moment when words became action, and when the fate of millions hung on the precision of a single signature.

Why Kennedy Chose a Quarantine: Strategy at the Edge of War

Picketers representing an organization known as Women Strike for Peace carry placards outside the United Nations headquarters in New York City, Oct. 23, 1962. (Credit: The Atlantic)

In the crucible of October 1962, President John F. Kennedy faced a decision that would shape the fate of the world. With Soviet nuclear missiles discovered in Cuba—just 90 miles from Florida—the pressure to act swiftly and decisively was immense. Among the options presented by his advisors were airstrikes to destroy the missile sites, a full-scale invasion of Cuba, or a more measured approach: a naval quarantine. Kennedy chose the latter, not out of weakness, but out of a calculated desire to avoid catastrophe.

A military strike, while potentially effective in eliminating the missile threat, carried the grave risk of igniting a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union. There was no guarantee that all missile sites could be destroyed in a single blow, and such an attack might provoke a retaliatory strike—not just in Cuba, but perhaps against U.S. allies or even the homeland. Kennedy understood that the world stood on a knife’s edge, and that any misstep could plunge it into nuclear war.

The quarantine offered a strategic middle ground. By halting the delivery of additional offensive weapons to Cuba, the United States could assert its resolve without immediately resorting to violence. It was a move that bought time—time for diplomacy, for backchannel negotiations, and for the Soviets to reconsider their course. Rather than striking the missile sites already in place, Kennedy focused on preventing the situation from worsening, thereby preserving the possibility of a peaceful resolution.

Internationally, the quarantine gained critical legitimacy. The Organization of American States (OAS) quickly endorsed the action, framing it as a collective defense of the Western Hemisphere. This support was essential in countering Soviet claims of American aggression and in reinforcing the idea that the U.S. was acting not unilaterally, but in concert with its neighbors. Kennedy’s team worked tirelessly to present the quarantine as a lawful, proportionate response to a clear and present danger.

Domestically, the move allowed Kennedy to speak directly to the American people—and to the world—with clarity and moral authority. In his televised address on October 22, he made it clear that the United States would not tolerate offensive nuclear weapons in Cuba, but that it would respond with restraint and legality. The language of the proclamation and the tone of the address were carefully calibrated to project strength without provocation.

In the broader arc of the crisis, Proclamation 3504 became the legal and symbolic backbone of the U.S. response. It marked the shift from secret deliberations to public enforcement, signaling to both allies and adversaries that the United States was prepared to act—but not to escalate recklessly. The document stands today as a powerful example of constitutional leadership under pressure, balancing military readiness with diplomatic finesse.

For the USA Radio Museum’s commemoration, this moment captures the essence of statesmanship in the nuclear age. It reminds us that sometimes, the most courageous act is not to strike first, but to hold the line—and to speak with both resolve and reason.

October 23, 1962: The Brink of Nuclear War

As dusk settled over Washington on October 23, 1962, President John F. Kennedy took pen to paper and signed Proclamation 3504, a document that would mark the transition from quiet deliberation to active enforcement. With that signature—made after 7:00 p.m.—the United States formally authorized a naval quarantine of Cuba, a term deliberately chosen to avoid the warlike connotation of “blockade.” This was a legal and diplomatic tightrope: the U.S. sought to halt the delivery of Soviet offensive weapons without triggering a declaration of war under international law.

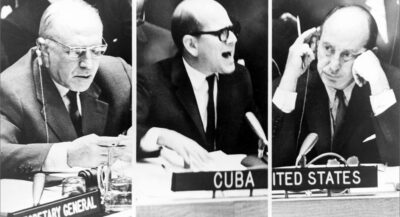

A composite image of three photograph taken on October 23, 1962, during a United Nations Security Council meeting on the Cuban Missile Crisis. From left, Soviet foreign deputy minister Valerian A. Zorin; Cuba’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Mario Garcia-Inchaustegui; and U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson. (Credit: The Atlantic)

The quarantine was not symbolic. Within hours, U.S. Navy vessels had formed a perimeter around the island, tasked with intercepting and inspecting any ship suspected of carrying military cargo. The tension was immediate and visceral. Soviet freighters en route to Cuba began to slow, some halting altogether in the Atlantic, uncertain whether to challenge the American line. But one ship—the Soviet oil tanker Bucharest—pressed forward, a deliberate test of U.S. resolve. Meanwhile, Soviet submarines slipped into the Caribbean, their silent presence adding a layer of danger that could not be seen but was deeply felt. The possibility of underwater confrontation loomed large.

On the diplomatic front, the crisis was now fully international. At the United Nations, U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson stood before the Security Council and laid out photographic evidence of Soviet missile installations in Cuba. His presentation was calm but devastating, a public unveiling of what had been, until then, a secret threat. Simultaneously, Assistant Secretary of State Edwin Martin worked to secure hemispheric support through the Organization of American States (OAS). Their resolution condemned Soviet actions and endorsed the quarantine, giving Kennedy’s move a crucial layer of legitimacy.

Yet the most consequential diplomacy that day happened behind closed doors. That evening, Robert F. Kennedy, the President’s brother and closest advisor, met privately with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin at the Soviet Embassy in Washington. In that quiet room, away from cameras and microphones, the two men began to sketch the outlines of a possible resolution. It was the beginning of a back-channel that would prove vital in the days to come.

October 23 was not the climax of the Cuban Missile Crisis—but it was the hinge. It was the day the world moved from discovery to confrontation, from secrecy to enforcement. And through it all, radio carried the story. NBC’s 24-minute report, preserved in your museum’s archive, captured the pulse of a nation on edge. It is more than a broadcast—it is a time capsule of fear, resolve, and the fragile hope that reason might yet prevail.

Postscript: The Final Days of the Crisis (October 24–28, 1962)

The days following October 23 were among the most perilous in human history. With the naval quarantine in place, the world watched as Soviet ships approached the U.S. blockade line. Would they stop—or would the Cold War turn hot?

October 24:

The first direct test of the quarantine arrives. Soviet ships en route to Cuba slow down or reverse course, avoiding confrontation. However, U.S. reconnaissance flights confirm that missile site construction in Cuba continues. Tensions remain sky-high.

October 25:

At the United Nations, U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson confronts Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin in a dramatic televised exchange. When Zorin refuses to confirm or deny the presence of missiles, Stevenson famously demands, “I am prepared to wait for my answer until Hell freezes over.” He then presents photographic evidence of the missile sites, stunning the world.

October 26:

A letter from Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev arrives at the White House. It is emotional and personal in tone, suggesting a deal: the USSR will remove its missiles from Cuba if the U.S. pledges not to invade the island.

October 27:

The most dangerous day of the crisis. A second, more formal letter from Khrushchev demands the removal of U.S. Jupiter missiles from Turkey in exchange for Soviet withdrawal from Cuba. That same day, a U.S. U-2 spy plane is shot down over Cuba, killing pilot Major Rudolf Anderson Jr. The world stands on the brink.

October 28:

President Kennedy, advised by his brother Robert F. Kennedy, chooses to respond only to Khrushchev’s first letter. In a carefully worded reply, he agrees not to invade Cuba if the missiles are removed. Behind the scenes, the U.S. also privately agrees to remove its missiles from Turkey within a few months. Khrushchev accepts. The crisis is over.

November 20, 1962:

After confirming the dismantling and removal of Soviet missiles and bombers from Cuba, the United States formally ends the quarantine. The 13-day standoff that brought the world to the edge of nuclear war has concluded.

_____________________

The Hidden Threat: What We Didn’t Know in 1962 Until 1992

For decades, the Cuban Missile Crisis was remembered as a narrowly avoided strategic nuclear showdown between Washington and Moscow. But in 1992, at a historic conference in Havana marking the 30th anniversary of the crisis, a chilling truth emerged: Cuba had tactical nuclear weapons on the ground—ready to be used against U.S. forces in the event of an invasion.

For decades, the Cuban Missile Crisis was remembered as a narrowly avoided strategic nuclear showdown between Washington and Moscow. But in 1992, at a historic conference in Havana marking the 30th anniversary of the crisis, a chilling truth emerged: Cuba had tactical nuclear weapons on the ground—ready to be used against U.S. forces in the event of an invasion.

Soviet generals revealed that approximately 100 tactical nuclear warheads had been secretly deployed to Cuba in 1962. These included short-range missiles and nuclear artillery intended for battlefield use. Even more alarming, Soviet commanders in Cuba had operational control—meaning they could have launched these weapons without direct orders from Moscow.

Fidel Castro, present at the conference, confirmed that he had urged Khrushchev to consider a nuclear strike if Cuba were attacked. He believed an invasion was inevitable and that Cuba would be destroyed regardless—so he advocated for retaliation, even if it meant mutual annihilation.

This revelation reframed the crisis entirely. Had President Kennedy chosen to invade Cuba—as many in his military circle advised—the result might have been nuclear war on the battlefield, with unimaginable consequences. His decision to pursue a quarantine instead of an airstrike or invasion may have saved not just American lives, but the future of civilization itself.

The 1992 disclosures remind us that history is not static—it evolves as new truths emerge. And they reaffirm the legacy of Kennedy’s leadership: a man who chose restraint over aggression, diplomacy over destruction, and peace over peril.

_____________________

Epilogue: A President Remembered

In the decades since those fateful October days, history has returned again and again to the image of President John F. Kennedy, seated in the Cabinet Room, surrounded by his advisors, bearing the weight of the world. The Cuban Missile Crisis was not just the defining moment of his presidency—it was a defining moment for humanity.

Kennedy’s decision to pursue a measured, diplomatic path rather than a preemptive strike was not without risk. He faced pressure from military leaders urging immediate action, and he knew that any miscalculation could unleash a nuclear holocaust. Yet he chose restraint over retaliation, dialogue over destruction. His leadership during those 13 days is now widely regarded as a masterclass in crisis management, blending strategic firmness with moral clarity.

President John Kennedy reports personally to the nation on the status of the Cuban crisis, telling the American people that Soviet missile bases in Cuba are “being destroyed”, on November 2, 1962. He said U.S. air surveillance will continue until effective international inspection is arranged. (Credit: The Atlantic)

When President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963, the nation mourned not only a young leader cut down in his prime, but the man who had steered the world away from the abyss. In the years since, his handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis has become a cornerstone of his legacy—a moment when calm judgment, empathy, and courage prevailed over fear and fury.

For the USA Radio Museum, this story is more than history. It is a testament to the power of communication, the role of media in shaping public understanding, and the enduring impact of leadership in times of peril. The voices captured in your 24-minute NBC Radio Report are echoes of a world that came within hours of annihilation—and of a President who helped pull it back.

Let us remember John F. Kennedy not only as the man who inspired a generation with the call to “ask what you can do for your country,” but as the steady hand who, when the world trembled, chose a different path. In the face of unimaginable pressure, he rejected the impulse to strike and instead pursued a course of measured restraint, strategic clarity, and moral courage.

His decision to enact a quarantine rather than launch an attack gave diplomacy a chance to breathe—and gave humanity a chance to survive.

Months later, in his Peace Speech he gave in June 1963 at American University, Kennedy would articulate the deeper vision behind his actions, as he implored for lasting peace to the world:

“What kind of peace do I mean? What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children–not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women–not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.

“Some say that it is useless to speak of world peace or world law or world disarmament–and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitude–as individuals and as a Nation–for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward–by examining his own attitude toward the possibilities of peace, toward the Soviet Union, toward the course of the cold war and toward freedom and peace here at home.

“So, let us not be blind to our differences–but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

That vision, forged in the crucible of the Cuban Missile Crisis, remains one of his most enduring legacies, spoken in words. And though his life was tragically cut short in Dallas just a year after those thirteen days the world experienced in October of 1962, history remembers him as the President who stood firm when the stakes were highest, who defused the most dangerous confrontation of the nuclear age, and who reminded us all that the greatest strength is through self-examination. And that strength lies not in power nor through the strategies of war—but lies in the hope for a better world through just and lasting peace.

_____________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_____________________

Photo credits courtesy of: The Atlantic; October 15, 2012

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.