Revolver at No.1: The Beatles’ Sonic Revolution September 10, 1966 — A Turning Point In the waning days of summer 1966, America found itself in a

Revolver at No.1: The Beatles’ Sonic Revolution

September 10, 1966 — A Turning Point

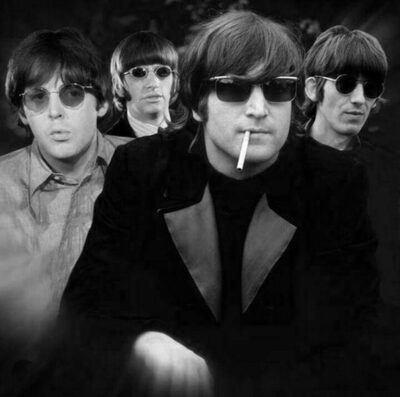

In the waning days of summer 1966, America found itself in a moment of cultural flux. The Vietnam War loomed large, civil rights tensions simmered, and the youth of the nation were beginning to question everything—from politics to pop music. Amid this backdrop, four young men from Liverpool quietly reshaped the sonic landscape. On September 10, Revolver—the Beatles’ seventh studio album—ascended to No.1 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, beginning a six-week reign that would mark not just commercial success, but a seismic shift in what popular music could be.

The Beatles had just wrapped their final tour, a chaotic and exhausting run that ended in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park only weeks earlier. Disillusioned with live performance and increasingly drawn to the creative possibilities of the recording studio, the band retreated from the stage and turned inward. What emerged was Revolver, an album that didn’t just reflect their evolution—it accelerated it. It was bold, experimental, and unapologetically strange. And yet, it resonated deeply with a public ready for something more than love songs and dance numbers.

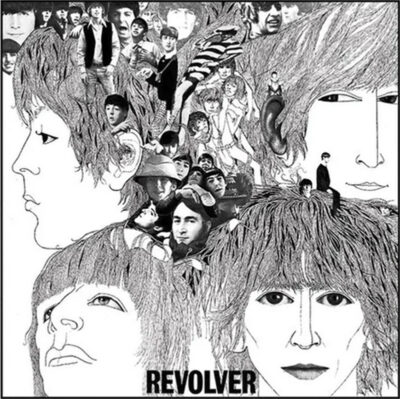

Even the title carried layered meaning. “Revolver” was a pun—at once a reference to a handgun and a nod to the revolving motion of a vinyl record spinning on a turntable. That duality mirrored the album’s impact: explosive in its innovation, yet cyclical in its influence, echoing through generations of musicians and listeners. It was a revolution that turned, and turned again.

As Revolver climbed the charts, it wasn’t just another Beatles album—it was a declaration. The mop tops were gone. In their place stood sonic architects, philosophers, and provocateurs. And radio, ever the amplifier of cultural change, was about to help broadcast this revolution into every living room, car, and transistor across the country. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Radio’s Role in the Rise

If Revolver was the Beatles’ boldest studio experiment to date, radio was its most vital translator. In 1966, the average listener didn’t have access to liner notes or studio breakdowns—they had DJs. Trusted voices who spun vinyl, shaped taste, and bridged the gap between innovation and understanding. As Revolver hit American shelves, it was radio that gave the album its wings.

If Revolver was the Beatles’ boldest studio experiment to date, radio was its most vital translator. In 1966, the average listener didn’t have access to liner notes or studio breakdowns—they had DJs. Trusted voices who spun vinyl, shaped taste, and bridged the gap between innovation and understanding. As Revolver hit American shelves, it was radio that gave the album its wings.

By the beginning of 1966, the Beatles were already a popular, world-wide brand. Stations across the country didn’t just play the Beatles—they championed them. Radio airchecks from the era reveal a palpable excitement, a sense that something new was happening. When “Eleanor Rigby” aired, it wasn’t just a song—it was a story. A string-laden lament for loneliness, introduced not with fanfare, but with quiet awe. “Tomorrow Never Knows,” with its swirling tape loops and hypnotic drone, was treated like a transmission from another planet. And “Yellow Submarine”? A whimsical singalong that gave kids and adults alike a reason to smile.

Radio made Revolver accessible. It softened the edges of its experimentation, contextualized its strangeness, and celebrated its brilliance. DJs became curators, guiding listeners through the album’s emotional terrain. They didn’t shy away from the philosophical or psychedelic—they leaned in, offering commentary, interviews, and even thematic programming that mirrored the album’s mood.

In a time before streaming, before algorithmic playlists, radio was the heartbeat of musical discovery. And in the fall of 1966, that heartbeat pulsed with the rhythms of Revolver. The album didn’t just climb the charts—it infiltrated the airwaves, becoming part of the daily soundtrack of American life. Whether in a Detroit diner, a California convertible, or a New York apartment, listeners heard the revolution—and it was spinning at 33⅓ RPM.

Studio Alchemy: The Beatles Go Avant-Garde

In the spring of 1966, the Beatles stepped into EMI Studios not as pop stars, but as sonic sculptors. The decision to stop touring had liberated them from the limitations of live performance, and with that freedom came a bold new ambition: to make records that couldn’t be replicated on stage. Revolver was their first full dive into that philosophy—a studio album in the truest sense, where every sound was crafted, manipulated, and layered with intention.

In the spring of 1966, the Beatles stepped into EMI Studios not as pop stars, but as sonic sculptors. The decision to stop touring had liberated them from the limitations of live performance, and with that freedom came a bold new ambition: to make records that couldn’t be replicated on stage. Revolver was their first full dive into that philosophy—a studio album in the truest sense, where every sound was crafted, manipulated, and layered with intention.

George Martin, their trusted producer, and Geoff Emerick, newly promoted to chief engineer, became co-conspirators in this creative leap. Emerick’s fresh approach to recording—placing microphones closer to instruments, experimenting with distortion, and embracing unconventional techniques—gave the album its distinctive punch. Ringo’s drums sounded deeper, Paul’s bass more melodic and forward, and John’s vocals more ethereal than ever before.

“Tomorrow Never Knows,” the album’s closing track, was a revelation. Lennon had envisioned a sound that felt like a Tibetan monk chanting from a mountaintop, and the team delivered. His voice was fed through a Leslie speaker, creating a swirling, otherworldly effect. Tape loops—assembled by McCartney using snippets of orchestral swells, seagull-like laughter, and reversed guitar riffs—were layered into the mix, turning the song into a psychedelic vortex. It was unlike anything heard on mainstream radio, and yet it became a cornerstone of the Beatles’ legacy.

Elsewhere, the band continued to push boundaries. “I’m Only Sleeping” featured a backwards guitar solo, meticulously recorded and reversed to achieve its dreamy, liquid texture. Harrison’s “Love You To” introduced Indian classical music to the pop canon, with sitar and tabla weaving through modal melodies that defied Western structure. And “Eleanor Rigby,” stripped of guitars and drums, relied solely on a string octet to deliver its haunting tale of loneliness—an audacious move that blurred the line between pop and chamber music.

Even the playful “Yellow Submarine” was a masterclass in studio creativity. Sound effects—clinking chains, bubbling water, nautical bells—were layered to create an immersive audio journey. Friends like Brian Jones and Marianne Faithfull reportedly joined the band in the studio to contribute background vocals and whimsical noises, turning the track into a communal celebration of imagination.

With Revolver, the Beatles didn’t just record songs—they built soundscapes. They treated the studio as a canvas, painting with frequencies, textures, and time itself. It was a revolution of process as much as product, and it set the stage for everything that followed—from Sgt. Pepper to the experimental heights of The White Album. In 1966, the Beatles didn’t just evolve—they exploded outward, and Revolver was the blast radius.

Threads of Psychedelia and Philosophy

If Revolver was a sonic revolution, its lyrics were a philosophical awakening. Gone were the simple love songs and teenage anthems of earlier Beatles records. In their place came meditations on death, consciousness, solitude, and spiritual yearning—each track a window into the shifting psyche of the mid-1960s.

“Eleanor Rigby” stands as one of the most haunting portraits of isolation ever committed to vinyl. With its stark string octet and absence of guitars or drums, the song reads like a eulogy for the forgotten. Father McKenzie, writing sermons no one hears, and Eleanor herself, buried with no one to mourn—these characters weren’t just fictional; they were reflections of a society grappling with disconnection. McCartney’s lyrics, paired with George Martin’s classical arrangement, elevated pop into poetry.

Then came “Tomorrow Never Knows,” Lennon’s plunge into the psychedelic abyss. Inspired by Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience and the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the song urged listeners to “turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream.” It wasn’t just a lyric—it was a mantra. With its droning tambura, swirling tape loops, and hypnotic rhythm, the track became a sonic embodiment of transcendence, inviting listeners to shed ego and embrace the infinite.

George Harrison’s “Love You To” continued this spiritual thread, drawing directly from Indian philosophy and musical tradition. The sitar and tabla weren’t decorative—they were devotional. Harrison’s lyrics, urging listeners to “make love all day long,” were less about sensuality and more about presence, about living fully in the now. It was a call to abandon material concerns and seek something deeper.

Even the more conventional tracks carried philosophical weight. “I’m Only Sleeping” captured the surreal beauty of dreams and the desire to escape the grind of waking life. “For No One,” McCartney’s chamber-pop lament, dissected the quiet unraveling of a relationship with surgical precision. And “She Said She Said,” born from a conversation Lennon had with actor Peter Fonda about death, turned existential dread into melodic catharsis.

Together, these songs formed a tapestry of introspection and inquiry. Revolver didn’t just reflect the counterculture—it helped shape it. Its lyrics questioned reality, challenged norms, and invited listeners to explore the inner landscape as much as the outer world. In doing so, the Beatles became not just musicians, but philosophers of the pop age.

The US Release: A Trimmed Masterpiece

When Revolver arrived in the United States on August 8, 1966, it wasn’t quite the same album that had stunned British audiences just days earlier. Capitol Records, continuing its long-standing practice of reshaping UK Beatles releases for the American market, trimmed the tracklist from 14 songs to 11. The missing pieces—“I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Doctor Robert”—had already been siphoned off for the earlier Yesterday and Today compilation, leaving Revolver lighter, leaner, and arguably less psychedelic.

When Revolver arrived in the United States on August 8, 1966, it wasn’t quite the same album that had stunned British audiences just days earlier. Capitol Records, continuing its long-standing practice of reshaping UK Beatles releases for the American market, trimmed the tracklist from 14 songs to 11. The missing pieces—“I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Doctor Robert”—had already been siphoned off for the earlier Yesterday and Today compilation, leaving Revolver lighter, leaner, and arguably less psychedelic.

This wasn’t just a matter of sequencing—it was a shift in experience. The omitted tracks were among the most sonically adventurous, with backward guitar solos, surreal lyrics, and biting satire. Their absence dulled the album’s experimental edge, making the US version feel more like a bridge than a breakthrough. For American fans, Revolver was still revolutionary—but it was missing some of its most potent ammunition.

Enter radio.

Across the country, DJs became cultural custodians, restoring what Capitol had removed. Stations like WABC in New York, KYA in San Francisco, and CKLW in Detroit began spinning the missing tracks alongside the official Revolver cuts, creating a kind of unofficial restoration. “I’m Only Sleeping” found its way into late-night sets, its dreamy haze perfectly suited to the twilight hours. “And Your Bird Can Sing,” with its jangling guitars and cryptic lyrics, became a favorite among college stations. And “Doctor Robert,” Lennon’s sly nod to pharmaceutical escapism, was embraced by DJs who understood its wink and edge.

These radio champions didn’t just play the songs—they contextualized them. They introduced listeners to the idea that albums were more than collections of hits—they were statements, stories, sonic journeys. By weaving the missing tracks back into the airwaves, DJs helped American audiences experience Revolver as it was meant to be: complete, complex, and uncompromising.

It was a quiet act of rebellion, one that mirrored the Beatles’ own defiance of convention. And it underscored the power of radio—not just as a promotional tool, but as a cultural force. In 1966, when record labels made edits, radio made amends. And thanks to those voices behind the mic, Revolver continued to revolve in full.

Chart Triumph and Cultural Ripples

When Revolver hit No.1 on the Billboard Top LPs chart on September 10, 1966, it wasn’t just another feather in the Beatles’ cap—it was a coronation. The album held the top spot for six consecutive weeks in the United States, a testament to its magnetic pull despite its experimental edge. In the UK, it reigned for seven weeks, further solidifying the Beatles’ dominance on both sides of the Atlantic. But the numbers only tell part of the story. Revolver didn’t just top charts—it rewired them.

This was the moment when albums began to eclipse singles as the primary artistic statement in pop music. Revolver wasn’t built around a hit—it was built around a vision. And that vision resonated. Radio stations, once hesitant to play tracks that defied convention, began embracing the album’s deeper cuts. “She Said She Said” and “For No One” found airtime alongside “Yellow Submarine” and “Eleanor Rigby,” creating a mosaic of moods that reflected the complexity of the era.

The album’s release coincided with a turbulent chapter in Beatles history. Lennon’s controversial remark that the band was “more popular than Jesus” had sparked backlash across the American South, leading to record burnings and boycotts. Yet Revolver rose above the noise. Its artistic integrity, sonic innovation, and emotional depth transcended the headlines. It was proof that the Beatles were no longer just entertainers—they were cultural commentators.

The ripple effect was immediate. Musicians across genres took note. Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, already deep into Pet Sounds, saw Revolver as both a challenge and a companion. Jimi Hendrix, still on the cusp of fame, absorbed its psychedelic textures. And bands like Pink Floyd, the Byrds, and the Velvet Underground began pushing their own boundaries, inspired by the Beatles’ fearless approach.

Even outside music, Revolver left its mark. Its themes of existential questioning, spiritual exploration, and social alienation mirrored the growing counterculture movement. College campuses, art galleries, and underground publications began referencing the album—not just as entertainment, but as philosophy.

In short, Revolver didn’t just dominate the airwaves—it reshaped them. It turned pop into art, radio into ritual, and listeners into seekers. And as it spun on turntables across the country, it whispered a new possibility: that music could be more than catchy—it could be transcendent.

The Commemorative Box Set: Revolver Re-Imagined

In October 2022, EMI and Apple Corps unveiled a landmark reissue of Revolver, breathing new life into the Beatles’ 1966 masterpiece with a commemorative box set that was as ambitious as the album itself. Overseen by Giles Martin—son of original producer George Martin—and engineer Sam Okell, the re-release featured a brand-new stereo mix sourced directly from the original four-track master tapes. Using cutting-edge “de-mixing” technology developed by Peter Jackson’s WingNut Films, the team was able to isolate and enhance individual elements that had previously been fused together, revealing sonic details long buried in the grooves.

The result was revelatory. McCartney’s bass lines popped with newfound clarity, Lennon’s vocals shimmered with psychedelic nuance, and Ringo’s drumming gained a muscular presence that had only been hinted at in earlier mixes. For longtime fans and first-time listeners alike, it was like hearing Revolver for the first time—again.

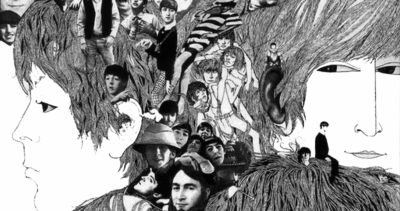

The Super Deluxe Edition came in two formats: a 5CD set and a 4LP+7″ vinyl set, each accompanied by a stunning 100-page hardcover book. The book featured Klaus Voormann’s iconic cover art, a foreword by Paul McCartney, essays by Questlove and Beatles historian Kevin Howlett, and reproductions of handwritten lyrics, tape boxes, and studio ephemera. It was more than packaging—it was a portal into the creative process.

Beyond the remixed album, the box set included two discs of studio sessions, outtakes, and demos, offering a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the making of Revolver. Listeners could hear alternate takes of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” early rehearsals of “Love You To,” and even a giggling version of “And Your Bird Can Sing” that captured the band’s irreverent spirit. A separate EP featured new stereo mixes and original mono versions of “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” two non-album singles recorded during the Revolver sessions.

Notably, the reissue omitted a physical Blu-ray disc, breaking from the precedent set by previous Beatles box sets. While an Atmos mix was created, it was made available only digitally, sparking debate among audiophiles and collectors. Still, the richness of the stereo and mono mixes, combined with the archival material, made the set a treasure trove for fans and curators alike.

For the USA Radio Museum, this reissue represents more than a remaster—it’s a reaffirmation. It proves that Revolver continues to evolve, to inspire, and to resonate. It’s a reminder that great art doesn’t fade—it deepens. And thanks to modern technology and reverent stewardship, this revolutionary LP sound the Beatles captivated in 1966 still turns.

Revolver Deluxe Edition: A Sonic Time Capsule Reopened

Step inside the studio where pop music became art. This immersive 3-hour presentation of the Revolver Deluxe Edition offers a front-row seat to the Beatles’ most daring transformation—where tape loops, string quartets, and psychedelic textures collided to redefine sound itself.

Featuring newly remixed tracks, rare outtakes, and archival gems, this expanded release reveals the creative heartbeat behind Revolver’s legacy. From the aching solitude of “Eleanor Rigby” to the cosmic swirl of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” every moment is a masterclass in innovation, emotion, and studio sorcery.

Whether you’re a lifelong fan or a curious newcomer, this is more than an album—it’s a revolution still unfolding.

▶️ Watch the full Deluxe Edition experience on YouTube

____________________

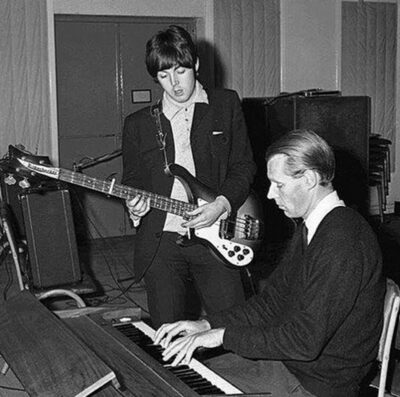

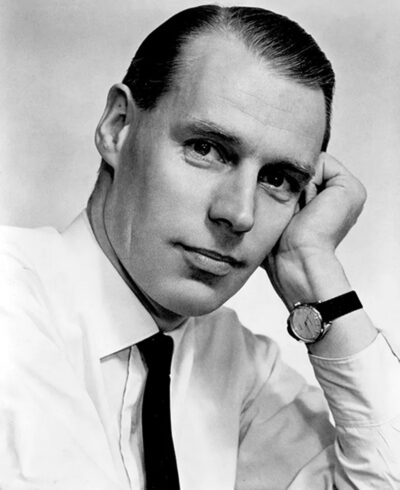

Sidebar: George Martin & the Studio Revolution

Often called “the Fifth Beatle,” George Martin was far more than a producer—he was the sonic architect behind the Beatles’ most daring musical experiments. On Revolver, Martin’s collaboration with the band reached new heights, as he helped transform Abbey Road Studios into a laboratory of sound.

Often called “the Fifth Beatle,” George Martin was far more than a producer—he was the sonic architect behind the Beatles’ most daring musical experiments. On Revolver, Martin’s collaboration with the band reached new heights, as he helped transform Abbey Road Studios into a laboratory of sound.

Working closely with 20-year-old engineer Geoff Emerick, Martin embraced radical techniques: close-miking Ringo’s drums (a practice previously forbidden at EMI), running Lennon’s vocals through a Leslie speaker to achieve the swirling effect on “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and orchestrating the haunting string octet for “Eleanor Rigby.” His classical training allowed him to bridge the gap between pop and avant-garde, guiding the band through tape loops, reversed recordings, and Indian instrumentation with precision and imagination.

Martin didn’t just facilitate the Beatles’ ideas—he elevated them. His ability to translate abstract concepts into tangible soundscapes made Revolver possible. As Giles Martin later reflected during the 2022 remix project, “My dad would say the sounds came from themselves and their willingness to innovate”. But it was George Martin’s stewardship that turned those ideas into enduring art.

_____________________

Closing Reflection: The Turning of Revolver

When Revolver spun onto turntables in 1966, it didn’t just mark the next chapter in the Beatles’ discography—it redefined the very language of popular music. It was a breakthrough in sound, yes, but more profoundly, it was a breakthrough in intent. The album catapulted the Beatles from pop prodigies to mature artists, unafraid to confront mortality, isolation, transcendence, and the surreal beauty of the subconscious.

When Revolver spun onto turntables in 1966, it didn’t just mark the next chapter in the Beatles’ discography—it redefined the very language of popular music. It was a breakthrough in sound, yes, but more profoundly, it was a breakthrough in intent. The album catapulted the Beatles from pop prodigies to mature artists, unafraid to confront mortality, isolation, transcendence, and the surreal beauty of the subconscious.

Gone were the days of formulaic love songs and stage-ready hits. In their place came poetic introspection, sonic experimentation, and a fearless embrace of the unknown. The Beatles no longer wrote for the charts—they wrote for the soul. And they no longer recorded to replicate live performance—they recorded to explore what sound could become when freed from physical limits.

With Revolver, the studio became their sanctuary. Tape loops, reversed guitars, Indian ragas, and string quartets weren’t gimmicks—they were tools of emotional expression. Each track was a vignette, each lyric a revelation. From the aching solitude of “Eleanor Rigby” to the cosmic surrender of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the album invited listeners to look inward, outward, and beyond.

It was the moment the Beatles grew up—not in age, but in artistry. And in doing so, they invited the world to grow with them. Revolver didn’t just reflect the spirit of its time—it shaped it. It turned the record player into a portal, the radio into a revolution, and the pop song into a canvas for the human condition.

Decades later, it still turns. And every rotation reminds us that sound, like memory, is never static—it evolves, deepens, and continues to resonate. Revolver was the Beatles’ leap into maturity, and for those who listen closely, it remains a timeless invitation to do the same.

Nearing the end of their historic touring years when the LP was released, the Beatles were prepared to leave behind the stage to embrace the studio as their creative frontier. Revolver captured a momentous cadence—a new sound forged within the walls of EMI, where innovation met introspection. Building on the reflective textures of Rubber Soul, Revolver pushed further into sonic experimentation and lyrical depth, setting the stage for the kaleidoscopic grandeur of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. In every sense, Revolver was the turning point—the moment the Beatles fully embraced their evolving role as studio visionaries and cultural architects, crafting and unveiling a bold new sound that resonated with fans, here in America, and across the globe.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.