Introduction: On This Day in Music History — February 15, 1965 There are days in American cultural history that feel suspended in time — days when

Introduction: On This Day in Music History — February 15, 1965

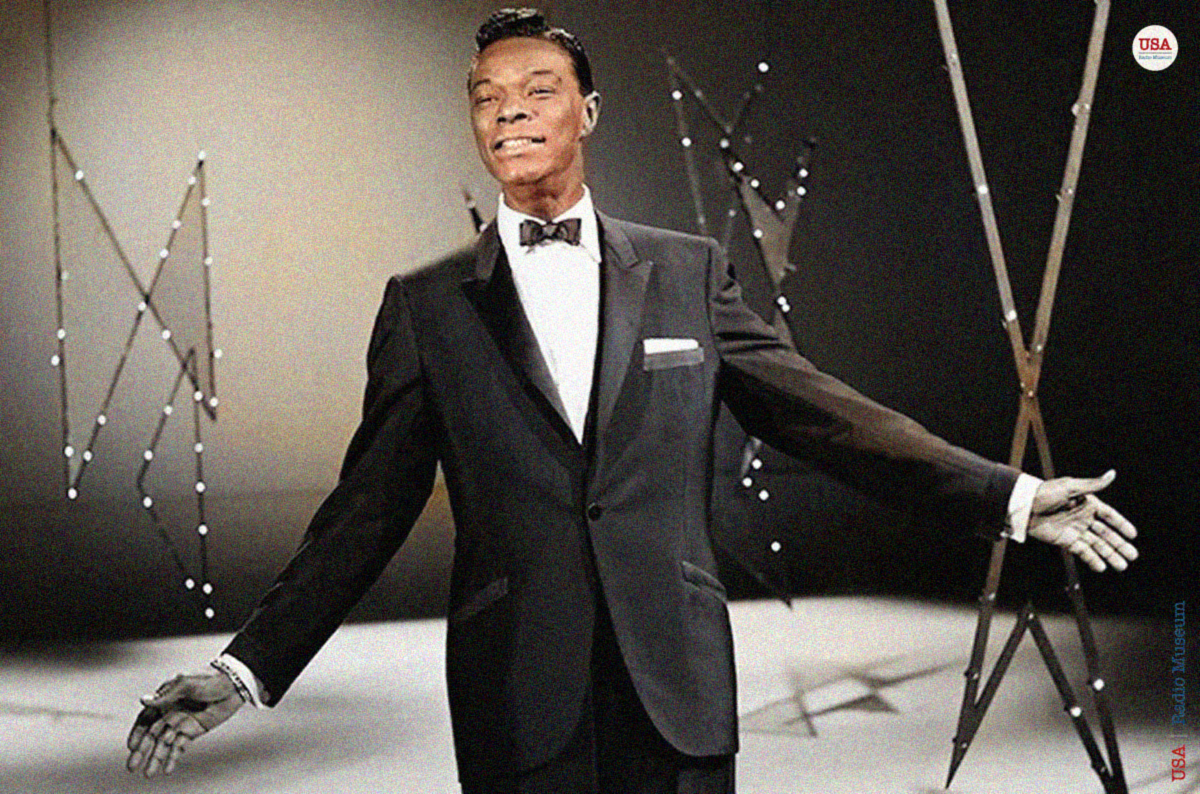

There are days in American cultural history that feel suspended in time — days when the loss of a single voice echoes far beyond the moment itself. February 15, 1965, stands among them. On that day, Nat King Cole, one of the most beloved and influential entertainers of the twentieth century, died of lung cancer at the age of forty‑five. His passing was not simply the end of a career. It was the silencing of a sound that had become part of the American soul.

There are days in American cultural history that feel suspended in time — days when the loss of a single voice echoes far beyond the moment itself. February 15, 1965, stands among them. On that day, Nat King Cole, one of the most beloved and influential entertainers of the twentieth century, died of lung cancer at the age of forty‑five. His passing was not simply the end of a career. It was the silencing of a sound that had become part of the American soul.

Nat King Cole’s voice was more than a musical instrument. It was a companion — warm, velvety, intimate, and instantly recognizable. For millions, he was the voice that drifted through living rooms on quiet evenings, the presence that softened the edges of a hard day, the artist who made every lyric feel personal. His death left a void that could be felt across radio, television, records, and the hearts of listeners around the world. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

A Voice That Defined an Era

Born Nathaniel Adams Coles in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1919 and raised in Chicago, Cole’s earliest musical identity was shaped at the piano. Before he ever became known as a singer, he was already a jazz pianist of remarkable sensitivity and swing. With guitarist Oscar Moore and bassist Wesley Prince, he formed the King Cole Trio, a group whose tight interplay and understated sophistication helped define the sound of West Coast jazz in the 1940s.

Born Nathaniel Adams Coles in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1919 and raised in Chicago, Cole’s earliest musical identity was shaped at the piano. Before he ever became known as a singer, he was already a jazz pianist of remarkable sensitivity and swing. With guitarist Oscar Moore and bassist Wesley Prince, he formed the King Cole Trio, a group whose tight interplay and understated sophistication helped define the sound of West Coast jazz in the 1940s.

But it was Cole’s voice — that warm, unhurried baritone — that would make him immortal. Songs such as “Nature Boy,” “Mona Lisa,” “Too Young,” “Unforgettable,” and “Smile” became woven into the emotional fabric of American life. His phrasing was effortless, his diction precise, his delivery intimate. He made singing sound natural, conversational, and deeply human.

By the 1950s, Nat King Cole was one of the most successful recording artists in the world. He crossed genres with ease, moving from jazz to pop to ballads to standards, and even into country. Over the course of his career, he recorded more than one hundred hit songs — a staggering achievement by any measure.

Yet his influence extended far beyond the music itself.

A Pioneer in Radio and Television

In an era when segregation still shaped much of American life, Nat King Cole broke barriers simply by being seen and heard.

In an era when segregation still shaped much of American life, Nat King Cole broke barriers simply by being seen and heard.

On radio, he made history with King Cole Trio Time, the first radio program ever sponsored by Black musicians. It was a milestone not only for Cole but for American broadcasting, signaling a shift in who could lead, who could host, and who could represent the nation’s cultural voice.

On television, he broke even more ground. In 1956, Cole became the first Black host of a national television series with The Nat King Cole Show. Though critically acclaimed, the program struggled to secure national sponsorship — a reflection of the racial climate of the time, not of Cole’s talent or popularity. After sixty‑four weeks, the show ended. Cole, with characteristic grace and candor, remarked, “Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark.”

His courage in stepping into that role — knowing the obstacles — opened doors for generations of Black performers who would follow.

The Final Chapter

By late 1964, Cole’s health had begun to decline. What the public first heard described as a “respiratory ailment” was soon revealed to be far more serious. He was admitted to St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica in December, just two days before he was scheduled to headline the inaugural popular music and jazz concert at the brand‑new Music Center. X‑rays revealed a malignant tumor in his left lung. Cobalt treatments began immediately, and Frank Sinatra stepped in to lead the Music Center concert in Cole’s place.

Cole underwent surgery in January to remove the lung, and for a brief moment he believed he was recovering. His wife, Maria, shielded him from the truth as long as she could. She released optimistic statements to the press — written in his voice — because he watched television constantly and she didn’t want him to see the speculation about his condition. Even in the hospital, he remained gracious, welcoming Jack Benny for a quiet fifteen‑minute visit when Benny happened to be on the same floor.

But the disease had already spread. The death of Cole’s father two weeks earlier weighed heavily on him; family members later said they saw him change the moment he learned the news. Still, he held onto hope. Only the day before his death, Maria took him for a short car ride. A few days earlier, he had visited his children at their Hancock Park home — a final moment of normalcy.

On February 15, 1965, Nat King Cole died peacefully in his sleep. He was pronounced dead at 5:30 a.m. The entertainment world was stunned. Maria had succeeded in keeping the severity of his illness private — from the public, and heart-breakingly, from him.

A City in Mourning

Los Angeles responded with an outpouring of grief. The City Council adjourned in his memory. Flags at the Music Center — where he was a Founder — were lowered to half‑staff. His sealed casket was placed at St. James Episcopal Church for public viewing the day before the funeral, and thousands came to pay their respects.

On February 27, the funeral itself became one of the most extraordinary gatherings in entertainment history. Inside St. James Episcopal Church, four hundred friends and family filled the pews. Outside, an estimated three thousand people stood shoulder to shoulder, lining the sidewalks in quiet reverence.

A procession of limousines brought an extraordinary cross‑section of American entertainment. Frank Sinatra arrived, followed by Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, Edie Adams, Gene Barry, Jose Ferrer, Rosemary Clooney, Danny Thomas, Vic Damone, Sammy Davis Jr., Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Frankie Laine, and George Jessel. Their presence reflected not only Cole’s stature as an artist but the deep affection he inspired among his peers.

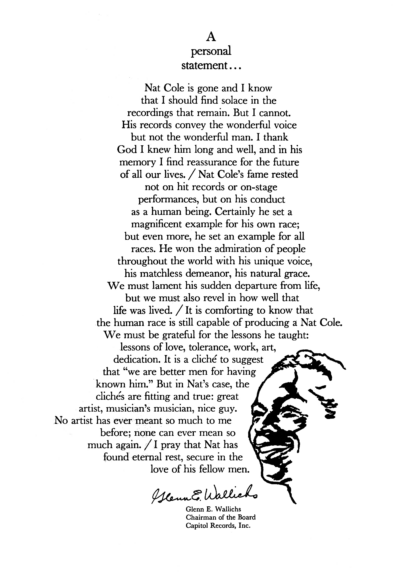

When the silver hearse pulled up to the church, the bronze casket was carried by pallbearers James Conkling, former president of Warner Bros. Records; Glenn Wallichs, chairman of Capitol Records; Harold Plant, Cole’s business manager; and Henry Miller, his agent.

Jack Benny delivered the eulogy. His words, spoken with visible emotion, captured the heartbreak of the moment: “Nat Cole was an institution, a tremendous success as an entertainer, but an even greater success as a man, husband, father and friend.”

Honorary pallbearers included Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Ricardo Montalbán, George Burns, Nelson Riddle, Gordon Jenkins, Peter Lawford, Edward G. Robinson, Governor Edmund G. Brown of California, Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York, and Count Basie.

After the service, the procession moved to Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale for a brief interment ceremony. Cole was survived by his wife, Maria; their children Kelly, Timolin, Casey, Carol, and Natalie; and his siblings Edward, Fred, and Evelyn.

_____________________

A SIDEBAR — The Christmas Song: The Timeless Classic That Found its Perfect Voice

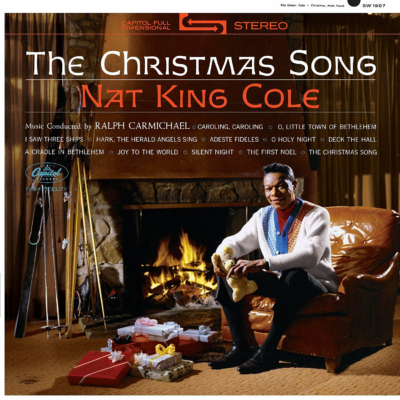

Among the many recordings that define Nat King Cole’s legacy, none has achieved the cultural permanence of “The Christmas Song.” Written in 1945 by Mel Tormé and Robert Wells during a blistering Los Angeles summer, the song was conceived as a lyrical escape from the heat. Wells had jotted down a few winter‑themed phrases — chestnuts roasting, Jack Frost nipping, Yuletide carols — in an attempt to imagine cold weather. Within forty minutes, the two had completed what would become one of the most beloved holiday songs ever written.

Among the many recordings that define Nat King Cole’s legacy, none has achieved the cultural permanence of “The Christmas Song.” Written in 1945 by Mel Tormé and Robert Wells during a blistering Los Angeles summer, the song was conceived as a lyrical escape from the heat. Wells had jotted down a few winter‑themed phrases — chestnuts roasting, Jack Frost nipping, Yuletide carols — in an attempt to imagine cold weather. Within forty minutes, the two had completed what would become one of the most beloved holiday songs ever written.

Cole recognized its potential immediately. He first recorded the song with his trio in 1946, but he believed it deserved a grander setting. Later that same year, he re‑recorded it with a full orchestra, revealing the song’s true emotional depth. His warm baritone wrapped itself around the melody with a tenderness that felt both intimate and universal.

He revisited the song in 1953 and again in 1961, the version most listeners know today. Each interpretation deepened the sense of nostalgia, comfort, and quiet wonder that became synonymous with Cole’s voice. For many, his rendition is not simply a performance — it is the definitive expression of the holiday spirit.

Every December, Cole’s recording returns to the charts, reclaims its place on radio playlists, and fills homes with the same gentle magic it carried more than sixty years ago. While countless artists have covered the song, none have displaced the version that feels as timeless as the season itself. Mel Tormé himself later acknowledged that Cole’s interpretation elevated the song beyond anything he could have imagined.

For generations of listeners, Christmas does not truly begin until Nat King Cole sings those first few words . . . “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire. Jack frost nipping at your nose . . . .”

_____________________

A Nation of Radio Stations Pays Tribute

In the days following his death, radio — the medium that had carried Cole from jazz clubs to living rooms — responded with a wave of tributes across the country.

In New York, WLIB devoted an entire “Nat King Cole Day” to his memory, with each on‑air personality highlighting a different facet of his artistry: his sacred recordings, his jazz work, his pop ballads, and his rhythm‑and‑blues roots.

In Philadelphia, WIP produced a special tribute in cooperation with the American Cancer Society.

WHN in New York, one of the first stations to salute him, played a different Nat King Cole recording every half hour. Earlier that month, as news of his illness spread, the station had urged listeners to send cards and letters of encouragement — and thousands did.

Across the nation, stations large and small filled their airwaves with his music. It was a collective acknowledgment that Nat King Cole had not merely been a star — he had been part of the soundtrack of American life.

“Long Live the King”

In its February 27, 1965 issue, Billboard published an editorial that distilled the nation’s grief into four simple words: “Long live the King.” The tribute praised Cole’s musicianship, his showmanship, and his ability to remain relevant in an era of rapidly shifting musical tastes. But it was the closing sentiment that captured the essence of Nat King Cole: “Perhaps the greatest thing about him… is the fact that he was a gentleman in the true sense; that is, a gentle man.”

That distinction — between greatness and goodness — is what made Nat King Cole unique.

A Legacy That Endures

More than half a century after his passing, Nat King Cole’s influence remains profound. His recordings continue to sell. His holiday classic, “The Christmas Song,” returns to the charts every December. His phrasing, tone, and interpretive style remain touchstones for singers across genres. His pioneering work on radio and television opened doors that had long been closed. Every Black host who followed — from Flip Wilson to Oprah Winfrey — walked through a door Nat King Cole helped unlock.

More than half a century after his passing, Nat King Cole’s influence remains profound. His recordings continue to sell. His holiday classic, “The Christmas Song,” returns to the charts every December. His phrasing, tone, and interpretive style remain touchstones for singers across genres. His pioneering work on radio and television opened doors that had long been closed. Every Black host who followed — from Flip Wilson to Oprah Winfrey — walked through a door Nat King Cole helped unlock.

His daughter Natalie Cole carried his legacy forward with her own remarkable career, including the Grammy‑winning “Unforgettable… with Love,” a virtual duet with her father that introduced his voice to a new generation.

At the USA Radio Museum, we honor Nat King Cole not only for his music but for his impact on broadcasting, culture, and the American story. His voice was a bridge — between jazz and pop, between Black and white audiences, between the past and the future.

He was, in every sense, a king.

And on this day in music history, we pause to remember the man whose voice still warms the world, whose courage still inspires, and whose legacy still shines.

Long live the King.

______________________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

______________________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2026 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.