Introduction: CBS's 'The World Today' Douglas Edwards and the Birth of Broadcast Trust Step into the golden age of radio journalism, where The W

Introduction: CBS’s ‘The World Today’

Douglas Edwards and the Birth of Broadcast Trust

Step into the golden age of radio journalism, where The World Today offered Americans a daily window into global events—and where Douglas Edwards became the steady voice of clarity during war, peace, and transformation.

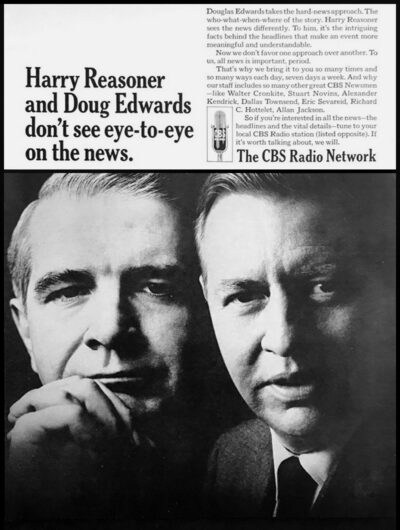

As anchor of CBS newscasts for 14 years, Edwards reported alongside legends like Edward R. Murrow, Bill Downs, and Winston Burdett, bringing unmatched journalistic rigor from foreign bureaus and war zones. In 1947, he made history again—becoming the first anchor of a nationally televised, regularly scheduled network newscast with Douglas Edwards with the News.

His tenure lasted until 1962, when Walter Cronkite succeeded him and the program became CBS Evening News. Edwards continued at CBS until 1988, marking over four decades of continuous network newscasting—a legacy of trust, integrity, and quiet authority.

At the USA Radio Museum, we honor Douglas Edwards not only as a pioneer of broadcast journalism, but as a voice that helped define what news could mean to a nation. — USA Radio Museum

_____________________

CBS News: The World Today with Douglas Edwards

“The World Today” was a pivotal CBS Radio news program that aired during World War II and into the postwar years, offering listeners a comprehensive roundup of global events. Douglas Edwards, one of the most trusted voices in American broadcasting, was a key figure in its presentation.

“The World Today” was a pivotal CBS Radio news program that aired during World War II and into the postwar years, offering listeners a comprehensive roundup of global events. Douglas Edwards, one of the most trusted voices in American broadcasting, was a key figure in its presentation.

Edwards anchored CBS newscasts for 14 years, and his voice became synonymous with clarity, calm, and credibility during some of the most turbulent moments in 20th-century history. He was part of a legendary CBS news team that included Edward R. Murrow, Bill Downs, and Winston Burdett—reporting from war zones and foreign bureaus with unmatched journalistic rigor.

The program evolved into Douglas Edwards with the News, which aired on CBS Television starting in 1947, making Edwards the first anchor of a nationally televised, regularly scheduled network newscast. He held that role until 1962, when Walter Cronkite succeeded him and the show was renamed CBS Evening News.

Edwards continued working for CBS until 1988, marking over 40 years of continuous network newscasting—a record unlikely to be broken. His legacy lives on as a pioneer of broadcast journalism and a trusted voice who helped define the role of the anchor in American media.

Origins: CBS and the Rise of Radio Journalism

Forging Trust in the Airwaves

By the late 1930s, Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) had emerged as more than a network—it had become a journalistic force. At the heart of this transformation was Edward R. Murrow, whose broadcasts from London during the Blitz didn’t just inform—they transported. With the crackle of air raid sirens behind him and the urgency of history unfolding in real time, Murrow’s voice became a conduit between war-torn Europe and the American living room.

Murrow’s impact wasn’t solitary. He assembled a cadre of correspondents who would become legendary in their own right: William L. Shirer, Eric Sevareid, Charles Collingwood, Howard K. Smith, and others—collectively known as the “Murrow Boys.” These journalists redefined war reporting by rejecting sanitized summaries in favor of vivid, firsthand accounts. They described bombed-out cities, battlefield conditions, and political upheaval with a clarity and immediacy that had never before reached the American public. Their work laid the foundation for modern broadcast journalism, where truth was not just told—it was felt.

Murrow’s impact wasn’t solitary. He assembled a cadre of correspondents who would become legendary in their own right: William L. Shirer, Eric Sevareid, Charles Collingwood, Howard K. Smith, and others—collectively known as the “Murrow Boys.” These journalists redefined war reporting by rejecting sanitized summaries in favor of vivid, firsthand accounts. They described bombed-out cities, battlefield conditions, and political upheaval with a clarity and immediacy that had never before reached the American public. Their work laid the foundation for modern broadcast journalism, where truth was not just told—it was felt.

Out of this ethos came The World Today, launched in the early 1940s as a daily digest of global events. It was CBS’s answer to a world in crisis—a program that balanced urgency with composure, breadth with depth. Airing in the late afternoon, it was strategically timed to reach listeners as they returned from work or gathered around the dinner table. The show’s rhythm was brisk but never rushed: dispatches from foreign bureaus, updates from Washington, battlefield briefings, and sober analysis—all delivered with journalistic rigor and emotional restraint.

What set The World Today apart was its tone. It didn’t sensationalize. It didn’t dramatize. Instead, it respected the intelligence and emotional bandwidth of its audience. Anchors like Douglas Edwards became trusted narrators, guiding listeners through the chaos with calm authority. The program’s structure mirrored the CBS philosophy: that news should be a public service, not a spectacle.

In many ways, The World Today was the connective tissue between Murrow’s wartime broadcasts and the rise of television news. It trained audiences to expect clarity, context, and credibility—and it trained journalists to deliver it. The program’s DNA would later evolve into Douglas Edwards with the News, and eventually CBS Evening News, but its origins remain rooted in a moment when radio journalism found its voice—and gave America one in return.

Columbia Broadcasting System | The World Today | Douglas Edwards | December 9, 1941

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

Douglas Edwards: The Voice of Credibility

Dignity in the Details, Trust in the Tone

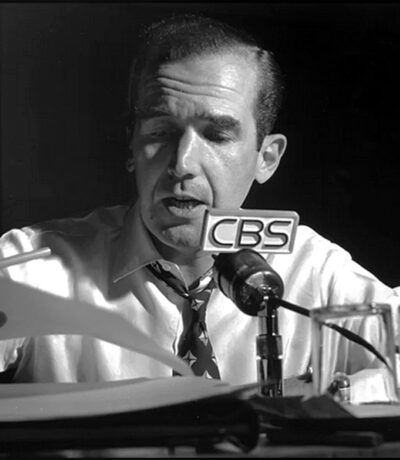

At a time when radio was the nation’s lifeline to the world, Douglas Edwards became its most trusted narrator. As the voice most associated with The World Today, Edwards didn’t just read the news—he embodied it. His delivery was calm, measured, and deeply reassuring, offering listeners not just information, but emotional ballast in an era defined by upheaval.

Edwards stood apart in a medium that could easily veer into sensationalism. He didn’t dramatize the headlines—he dignified them. His broadcasts reflected the CBS standard of “accuracy, not advocacy,” a guiding principle that valued clarity over commentary, and integrity over intrigue. In Edwards’ hands, the news was not a performance—it was a public service.

Listeners came to rely on him during the most consequential moments of the 20th century. Whether reporting on the Allied landings in Normandy, the liberation of Paris, or the grim realities of the Pacific theater, Edwards maintained a tone of quiet authority. His voice carried the weight of truth without theatrics, and his restraint became a form of respect—for the facts, for the audience, and for the lives behind the headlines.

What made Edwards exceptional was not just what he said, but how he made people feel. His broadcasts were emotionally grounding. In living rooms across America, families gathered around their radios not just to hear the news, but to hear it from him. He was a steady presence in a world that often felt unsteady—a voice that reminded listeners they were not alone in trying to make sense of it all.

Edwards’ legacy would later extend to television, where he became the first anchor of a nationally televised, regularly scheduled network newscast in 1947. But his roots in radio—particularly The World Today—cemented his place in history as a pioneer of broadcast credibility. He didn’t chase headlines. He earned trust. And in doing so, he helped define what it meant to be an anchor—not just of a program, but of a nation’s understanding.

_____________________

Sidebar Feature: What Americans Heard That Day

Date: August 22, 1944 – CBS News: The World Today

As families gathered around their Philco or Zenith radios, this is what poured through the speakers—news that felt immediate, urgent, and deeply personal.

Headlines from the Front:

• “Paris is rising.” Reports from London described fierce fighting between French Resistance forces and retreating German troops. The liberation was near.

• “Patton’s Third Army advances.” American forces were sweeping eastward, threatening German strongholds and accelerating the collapse of Nazi control in France.

• “Allied bombers strike deep.” Strategic air raids targeted German infrastructure, with CBS correspondents detailing the scale and precision of the attacks.

Voices They Trusted:

• Douglas Edwards, calm and composed, opened the broadcast with a summary of the day’s developments.

• Edward R. Murrow, reporting from London, painted a vivid picture of the mood in Europe: cautious optimism, tempered by the cost of war.

• Charles Collingwood, embedded with Allied troops, described the terrain, the morale, and the momentum of the advance.

News from Home:

• War bond drives surged as Americans responded to the call for continued support.

• Headlines from Washington hinted at Roosevelt’s reelection strategy, with speculation about his fourth term.

• Stories of wounded soldiers returning home reminded listeners of the human toll behind the headlines.

The Soundscape:

• The crackle of shortwave transmissions from Europe.

• The rhythmic clatter of teletype machines in the CBS newsroom.

• A brief orchestral swell between segments, underscoring the gravity of the moment.

Columbia Broadcasting System | The World Today | Douglas Edwards | August 22, 1944

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

The Murrow Boys and Global Coverage

Voices from the Front: Journalism That Traveled the World and Touched the Soul

What truly set The World Today apart was its global reach—a feat made possible by CBS’s pioneering use of shortwave radio and its bold investment in a network of foreign correspondents. In an era when most Americans relied on newspapers for international news, CBS shattered the boundaries of distance and delay. Through the static and hum of transatlantic signals, The World Today delivered live reports from London, Moscow, Cairo, Manila, and beyond—bringing the war home in real time.

These weren’t mere summaries. They were immersive narratives, shaped by journalists who risked their lives to bear witness. Known collectively as the Murrow Boys, these correspondents were handpicked by Edward R. Murrow not just for their skill, but for their integrity, intellect, and emotional depth. But before Murrow’s team took shape, one voice had already laid the groundwork for what broadcast journalism could be.

• Robert Trout: Often called the “Iron Man of Radio,” Trout was a master of live broadcasting, known for his composure, stamina, and eloquence. He hosted the first-ever multi-point shortwave broadcast on March 13, 1938, covering the Anschluss with reports from Murrow and William Shirer—a format that became the blueprint for World News Roundup. Trout’s ability to ad-lib under pressure and hand off coverage seamlessly made him one of the first true anchormen, and his mentorship helped shape Murrow’s own approach to radio. Trout’s voice was a constant presence throughout World War II, anchoring special reports and delivering news with clarity and gravitas.

• Edward R. Murrow: His broadcasts from London during the Blitz remain among the most powerful moments in broadcast history. Murrow didn’t just describe the bombs—he captured the resilience of a city under siege. His signature sign-off, “Good night, and good luck,” became a quiet anthem of courage and solidarity.

• Eric Sevareid: Reporting from France and later Asia, Sevareid infused his dispatches with literary grace and philosophical reflection. He didn’t just report on battles—he pondered the human cost of war, offering listeners a deeper understanding of its emotional toll.

• Charles Collingwood: His coverage of the Normandy invasion was groundbreaking, including live reports from the beaches—a technical and journalistic triumph. Collingwood’s voice carried the tension, chaos, and hope of D-Day with visceral immediacy.

• Howard K. Smith: From Berlin to Washington, Smith delivered sharp analysis and a nuanced grasp of political dynamics. His reports bridged the ideological divide of wartime Europe, helping Americans understand not just what was happening, but why.

Together, these voices gave The World Today a panoramic scope. Listeners weren’t just hearing about the war—they were experiencing it through the eyes and ears of journalists embedded in history. The program became a masterclass in global storytelling, blending urgency with empathy, and facts with feeling.

In honoring Robert Trout and the Murrow Boys, the USA Radio Museum celebrates not only their journalistic legacy, but their moral courage. They didn’t just report the news—they shaped how a nation understood its place in a rapidly changing world. And through The World Today, they proved that radio could be more than a medium—it could be a mirror, a witness, and a lifeline, especially to untold millions who depended on the latest news CBS radio broadcast from abroad during the Second World War.

Sound Design and Emotional Impact

The broadcasts were more than words—they were immersive experiences.

CBS didn’t just report the news; it sculpted it sonically. Behind every headline was a team of engineers, producers, and sound designers who understood that radio was not just a medium of information—it was a medium of emotion. They used ambient sound, battlefield recordings, and carefully timed silences to create a sense of immediacy that no newspaper could replicate.

The tick of a teletype machine conveyed urgency.

The crackle of shortwave static suggested distance and danger.

The low rumble of artillery, faint and ghostly, reminded listeners that the war was real—and still raging.

These sonic textures weren’t accidental. They were deliberate emotional cues, designed to place the listener inside the moment. A pause could speak louder than a paragraph. A swell of music could signal hope, dread, or solemnity.

One of the most powerful examples comes from an archived broadcast on June 6, 1944—D-Day. Douglas Edwards reads a bulletin announcing the Allied landings in Normandy. His voice is steady, but the gravity of the moment is palpable. After the bulletin, there’s a beat of silence—a breath held across the nation. Then, a brief orchestral swell rises, not triumphant, but reverent. It fades into the voice of Edward R. Murrow, reporting live from London with the sound of air raid sirens faintly audible in the background.

This wasn’t just reporting. It was cinematic storytelling, crafted in real time. The transitions between voices, the layering of ambient sound, and the pacing of each segment created a narrative arc—one that mirrored the emotional journey of the listener.

CBS’s wartime broadcasts became auditory monuments, capturing not just facts but feelings. They offered comfort, clarity, and connection in a time of global uncertainty. And they proved that radio, when wielded with intention and artistry, could be as powerful as any film or symphony.

Legacy and Cultural Resonance

These broadcasts didn’t just document history—they shaped how it was felt, remembered, and retold.

The wartime radio reports of CBS—anchored by voices like Douglas Edwards, Robert Trout, and Edward R. Murrow—became more than journalistic milestones. They became cultural touchstones, etched into the collective memory of a generation. For millions of Americans, these broadcasts were the soundtrack of uncertainty, resilience, and hope.

Families gathered around their living room radios not just to hear the news, but to feel connected—to soldiers overseas, to leaders in Washington, to fellow citizens navigating the same fears and dreams. The intimacy of radio made every bulletin personal. A pause in Trout’s delivery, a tremor in Murrow’s voice, a swell of orchestral music behind Edwards—these moments carried emotional weight that transcended the facts.

The broadcasts also helped define the ethics and aesthetics of modern journalism. They introduced the idea that news could be both factual and human, urgent and reflective. CBS’s commitment to accuracy, restraint, and emotional truth set a standard that would influence generations of reporters across media platforms.

Even decades later, the resonance remains. Audio clips from The World Today, World News Roundup, and special wartime bulletins are still studied in journalism schools, featured in documentaries, and preserved in museum archives like yours. They are living artifacts, not just of what happened, but of how it felt to live through it.

In the digital age, where news is often fragmented and fleeting, these broadcasts remind us of a time when storytelling was deliberate, voices were trusted, and sound itself was sacred. They are a testament to radio’s power—not just to inform, but to unite, comfort, and inspire.

Douglas Edwards: Honors and Legacy in Broadcasting

Hall of Fame Inductions

- Radio Hall of Fame (2006)

Recognized posthumously for his pioneering role in radio journalism and his decades-long contribution to CBS News. - NAB Broadcasting Hall of Fame (1991)

Celebrated for a 56-year career that spanned radio and television, from World War II to Watergate. - Georgia Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame (1986)

Honored for his early career roots and enduring influence in broadcast journalism. - Oklahoma Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame (1988)

A tribute to his home state and his foundational role in shaping national news delivery.

Major Awards and Recognitions

- Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Nominations

- Best News Reporter or Commentator (1954, 1955)

- Outstanding Program Achievement in News (1960, 1961)

- Writers Guild of America, East

- Award for Extraordinary Contributions to Broadcast Journalism

- Publicity Club of Boston – Bell Ringers Award (1977)

For excellence in public communication and media impact - DiGamma Kappa Distinguished Achievement in Broadcasting

University of Georgia, 1982 - Citation for Humanitarian Service

United Cerebral Palsy, recognizing Edwards’ advocacy and public service - Golden Anniversary Director’s Award

Oklahoma State University, 1986 - Honorary Doctorate

Saint Bonaventure University, Literarum Doctoris degree, 1967

Other Honors and Mementos

- Key to the City of Vicksburg

A symbolic gesture of civic appreciation - Commemorative Awards from WHNT-TV, KMSU-FM, and Brunswick Junior College

Celebrating milestones in Edwards’ career and his influence on local broadcasting communities - Panoramic Collage of CBS Newsmen (1985)

Featured alongside Walter Cronkite, Eric Sevareid, Dan Rather, and Andy Rooney—a visual testament to his place among legends

Robert Trout: The Iron Man of Radio

A Founding Voice of CBS News and The World Today

Born: October 15, 1909 – Washington, D.C.

Died: November 14, 2000 – New York City

Years Active: 1931–1999

Known As: “The Iron Man of Radio”

Before Edward R. Murrow’s voice echoed from London rooftops, before Douglas Edwards became the face of CBS Television News, there was Robert Trout—the man who helped invent the very language of broadcast journalism.

Trout began his career in 1931 as an announcer at WJSV in Alexandria, Virginia, which was acquired by CBS the following year. By the mid-1930s, he had already become a fixture on the network, known for his composure, stamina, and eloquence. He was the first to report live from Capitol Hill, the first to transmit from a flying airplane, and—by many definitions—the first true anchorman in broadcast history.

On March 13, 1938, Trout hosted the first-ever multi-point shortwave broadcast, linking CBS correspondents across Europe in response to Hitler’s annexation of Austria. That broadcast became the blueprint for World News Roundup, and later The World Today. Trout’s ability to ad-lib under pressure and hand off coverage with seamless grace made him the connective tissue of CBS’s wartime reporting.

His voice was a constant presence throughout World War II, anchoring special reports and delivering news with clarity and gravitas. Trout coined the term “fireside chat” for President Roosevelt’s radio addresses, and his broadcasts on V-E Day and the end of World War II remain among the most iconic moments in radio history.

On September 23, 1945, Trout anchored a postwar edition of The World Today, offering listeners a sober reflection on the global aftermath of conflict. That broadcast—now preserved in the USA Radio Museum’s archive—captures Trout’s signature blend of precision and empathy. He didn’t just report the news. He invited Americans to understand it.

Trout continued working with CBS for decades, making his final appearance in 1999, just months before his passing. His career spanned nearly 70 years, and his influence shaped generations of journalists who followed.

Columbia Broadcasting System | The World Today | Robert Trout | September 23, 1945

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

Major Awards & Recognitions

• George Foster Peabody Award (1979)

Awarded for “nearly 50 years of service as a thoroughly knowledgeable and articulate commentator on national and international affairs”. This is one of broadcasting’s highest honors, recognizing excellence in storytelling and public service.

• Peabody Award for Distinguished Public Service (1980)

A second Peabody, underscoring his enduring impact and integrity as a journalist.

• Induction into the NAB Broadcasting Hall of Fame (1987)

Celebrated as “The Iron Man of Radio,” Trout was honored for his live reports from Europe during WWII and his coverage of every U.S. presidential election since 1936.

Legacy and Preservation

From wartime urgency to peacetime continuity, The World Today became the foundation of modern broadcast journalism—and its echoes still resonate.

After the war, The World Today didn’t fade—it evolved. In 1947, CBS transitioned the program to television, rebranding it as Douglas Edwards with the News. Edwards, already a trusted voice from radio, became one of the first national TV news anchors in American history. His calm demeanor and journalistic integrity carried over seamlessly to the new medium, helping viewers navigate the postwar world, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and beyond.

Edwards remained a fixture at CBS until 1988, marking over four decades of continuous newscasting. His career bridged two eras—radio and television—and his legacy is inseparable from the evolution of American media. Yet the DNA of those early broadcasts—the pacing, the emotional clarity, the sonic storytelling—remained intact.

Today, the USA Radio Museum’s archive of The World Today broadcasts stands as one of the most comprehensive and carefully curated collections in existence. These recordings are not simply historical documents. They are living artifacts, rich with the voices, textures, and emotions of a nation in flux.

Each broadcast in the archive is a portal:

• To the anxious hush of a living room on D-Day

• To the crackle of shortwave as Murrow speaks from London

• To the measured cadence of Edwards delivering postwar headlines with quiet authority

Preserving these broadcasts is more than archival work—it’s cultural stewardship. The museum’s digitization efforts, curator annotations, and public storytelling initiatives ensure that these voices remain accessible, relevant, and emotionally resonant for future generations.

In an age of fleeting media and fractured attention, these broadcasts remind us of a time when journalism was crafted with care, when sound carried truth, and when radio was a lifeline between the world and the listener.

They are not relics.

They are testaments.

They are radio’s enduring heartbeat.

Reflections – Why It Still Matters

In an age of instant updates and digital saturation, The World Today reminds us what journalism can be at its most powerful: thoughtful, courageous, and deeply human.

The broadcasts of The World Today were never just about delivering information. They were about connection—between reporter and listener, between distant battlefields and quiet living rooms, between the chaos of history and the clarity of storytelling. In a time when the world was fractured by war, radio became the thread that held it together.

These voices—Edwards, Trout, Murrow—did more than narrate events. They guided a nation through uncertainty, offering not just facts, but empathy, reassurance, and resolve. Their words were measured, their silences meaningful, their tone a reflection of the emotional weight they carried on behalf of millions.

Today, in a media landscape defined by speed and brevity, these broadcasts stand as a counterpoint. They remind us that journalism is not just about being first—it’s about being true, being clear, and being human. They show us that storytelling, when done with care and conscience, can elevate news into something timeless.

For curators, historians, and listeners alike, these recordings are more than archival material. They are living echoes of a time when radio was the nation’s heartbeat. They speak to the enduring need for trustworthy voices, for shared experience, and for the kind of journalism that doesn’t just inform—but inspires, comforts, and unites.

In preserving The World Today, the USA Radio Museum isn’t just safeguarding history. It’s championing a legacy—one that continues to teach, resonate, and remind us of the profound power of sound sent through voices by way of news reports, as they occurred — as it happened.

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.