Introduction: Honoring Ruth Ann Meyer, Architect of Radio’s Golden Pulse In the annals of American broadcasting, few figures shaped the rhythm and

Introduction: Honoring Ruth Ann Meyer, Architect of Radio’s Golden Pulse

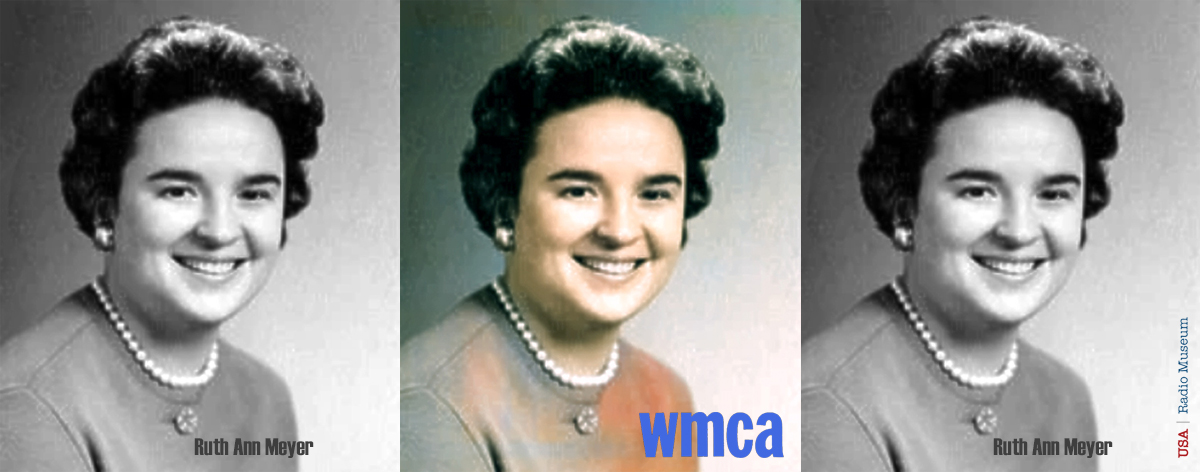

In the annals of American broadcasting, few figures shaped the rhythm and resonance of Top 40 radio like Ruth Ann Meyer. A visionary programmer, a pioneering woman in a male-dominated industry, and a master of team-driven radio identity, Meyer transformed stations into cultural institutions. Trained by Todd Storz—the very inventor of the Top 40 format—Ruth brought a rare blend of precision, creativity, and emotional intelligence to every frequency she touched.

In the annals of American broadcasting, few figures shaped the rhythm and resonance of Top 40 radio like Ruth Ann Meyer. A visionary programmer, a pioneering woman in a male-dominated industry, and a master of team-driven radio identity, Meyer transformed stations into cultural institutions. Trained by Todd Storz—the very inventor of the Top 40 format—Ruth brought a rare blend of precision, creativity, and emotional intelligence to every frequency she touched.

From her early days in Kansas City at WHB-AM to her groundbreaking leadership at WMCA in New York, Ruth redefined what it meant to program radio. She didn’t just hire talent—she built movements. Her creation of the “WMCA Good Guys” became a national model for branding and camaraderie, and her recruitment of Gary Stevens in 1965 to replace B. Mitchel Reed marked one of the most strategic talent moves in radio history.

This tribute article explores Ruth Ann Meyer’s extraordinary career—from her continuity desk to the command center of ABC Radio Networks—and celebrates the enduring legacy of a woman who programmed not just stations, but the very soundscape of a generation. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Kansas City Roots and the Storz School of Top 40

Long before she would shape the sound of New York radio, Ruth Ann Meyer was a young woman with a sharp mind and a quiet determination, growing up in Kansas City, Missouri. In the early 1950s, she entered the world of broadcasting through the back door—not as a DJ or producer, but in the continuity department at WHB-AM, a station owned by the visionary Todd Storz. At the time, continuity was considered clerical work: writing commercial copy, scheduling spots, and ensuring the station’s programming log ran smoothly. But Ruth saw it as a window into the machinery of radio—and she paid close attention.

WHB was no ordinary station. Under Storz’s leadership, it was becoming a laboratory for a radical new format: Top 40. Storz had observed that jukeboxes in diners and bars played the same handful of records over and over, and he theorized that radio listeners wanted the same thing—familiarity, repetition, and hits. He began programming WHB with a tight playlist of the most popular songs, rotating them frequently, and emphasizing personality-driven DJs who could connect with the audience.

WHB was no ordinary station. Under Storz’s leadership, it was becoming a laboratory for a radical new format: Top 40. Storz had observed that jukeboxes in diners and bars played the same handful of records over and over, and he theorized that radio listeners wanted the same thing—familiarity, repetition, and hits. He began programming WHB with a tight playlist of the most popular songs, rotating them frequently, and emphasizing personality-driven DJs who could connect with the audience.

Ruth was captivated. She watched as Storz’s formula turned WHB into a ratings powerhouse, and she absorbed every detail—how the music was selected, how the pacing was managed, how the DJs were coached. Her natural organizational skills and keen editorial sense didn’t go unnoticed. Storz, known for his instinctive eye for talent, saw something rare in Ruth: a woman who not only understood the format, but could think like a programmer.

In an era when women were rarely allowed beyond support roles in broadcasting, Storz made a bold move—he began training Ruth as a program director. It was an extraordinary opportunity, and Ruth seized it with both hands. She learned how to read audience research, how to balance music flow, how to manage air talent, and how to build a station identity. She studied the psychology of listener engagement and the art of creating momentum between records, commercials, and talk.

More than anything, she learned that radio was theater of the mind—and that a great programmer was both conductor and storyteller. Ruth’s time at WHB was her crucible. It was where she developed the skills, confidence, and vision that would soon carry her to the biggest stage in American radio.

By the late 1950s, Ruth had become one of the few women in the country with hands-on experience in Top 40 programming. She wasn’t just following a trend—she was helping to define it. And when opportunity knocked in New York City, she was ready to answer.

The WMCA Revolution

When Ruth Ann Meyer arrived in New York City in 1960, she stepped into a fiercely competitive radio landscape. WMCA 570 AM was a scrappy underdog, operating with just 5,000 watts compared to the 50,000-watt juggernaut WABC. But Ruth didn’t flinch. She brought with her the lessons of Todd Storz’s Top 40 formula—and a bold new idea: radio could be more than hit records and charismatic voices. It could be a team sport.

Her first order of business was to build a unified on-air identity. Rather than treating DJs as solo stars, Ruth envisioned a branded ensemble—The WMCA Good Guys. She handpicked a lineup of vibrant personalities: Harry Harrison, Dan Daniel, Jack Spector, Joe O’Brien, Ed Baer, and others. Each had a distinct voice, but Ruth insisted they operate as a collective. They wore matching suits, appeared together at public events, and even recorded a novelty album, “The Good Guys Sing.”

Her first order of business was to build a unified on-air identity. Rather than treating DJs as solo stars, Ruth envisioned a branded ensemble—The WMCA Good Guys. She handpicked a lineup of vibrant personalities: Harry Harrison, Dan Daniel, Jack Spector, Joe O’Brien, Ed Baer, and others. Each had a distinct voice, but Ruth insisted they operate as a collective. They wore matching suits, appeared together at public events, and even recorded a novelty album, “The Good Guys Sing.”

But Ruth’s genius wasn’t just in talent curation—it was in visual branding. She personally designed the iconic Good Guy sweatshirt logo, a cheerful cartoon figure that became a badge of honor among listeners. Fans clamored for the sweatshirts, and the logo appeared on bumper stickers, billboards, and promotional materials. It was radio branding at its most effective: simple, memorable, and emotionally resonant.

Under Ruth’s leadership, WMCA developed a compelling sound—tight playlists, energetic pacing, and a sense of fun that permeated every broadcast. She coached her DJs to be upbeat, relatable, and community-focused. Promotions like “Good Guy of the Week” and “Good Guy Goldies” created listener loyalty, while contests and call-ins kept the audience engaged.

By 1963, WMCA was gaining ground. In the five boroughs, it often beat WABC in ratings, despite its lower signal strength. Ruth’s programming philosophy—team unity, listener connection, and brand consistency—was working. WMCA became the epicenter of Beatlemania, the first station in New York to play “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and the Good Guys were seen as cultural ambassadors of the British Invasion.

Ruth’s influence extended beyond New York. The “Good Guys” concept was copied by Top 40 stations around the world, from Los Angeles to Sydney. Her approach to programming—treating radio as both performance and product—became the blueprint for modern music radio.

And yet, Ruth remained behind the scenes. She didn’t seek the spotlight. She let her DJs shine, her branding speak, and her programming deliver. In an industry dominated by male executives, Ruth Ann Meyer was quietly revolutionizing radio—one sweatshirt, one playlist, one team at a time.

The Gary Stevens Coup

By 1965, Ruth Ann Meyer had transformed WMCA into a cultural force. The “Good Guys” were household names, the station was riding high on Beatlemania, and Ruth’s programming philosophy—team unity, listener intimacy, and brand cohesion—was paying off in ratings and reputation. But radio is a fast-moving medium, and Ruth knew that momentum had to be maintained. When B. Mitchel Reed, one of WMCA’s most popular evening jocks, announced his departure for the West Coast, Ruth faced a critical decision.

By 1965, Ruth Ann Meyer had transformed WMCA into a cultural force. The “Good Guys” were household names, the station was riding high on Beatlemania, and Ruth’s programming philosophy—team unity, listener intimacy, and brand cohesion—was paying off in ratings and reputation. But radio is a fast-moving medium, and Ruth knew that momentum had to be maintained. When B. Mitchel Reed, one of WMCA’s most popular evening jocks, announced his departure for the West Coast, Ruth faced a critical decision.

Reed was a magnetic presence in the 7–11 p.m. slot, known for his hip delivery and deep connection to the youth audience. His move to Los Angeles would help shape the rise of progressive FM radio, but for Ruth, it created a void at a crucial time slot—one that went head-to-head with WABC’s Cousin Brucie, the reigning king of nighttime Top 40.

Ruth didn’t panic. She scouted the country, looking for a voice that could not only replace Reed but elevate WMCA’s brand. Her search led her to Detroit, where a young DJ named Gary Stevens was electrifying the airwaves at WKNR Keener 13. Stevens was fast-talking, funny, and fearless. He had helped Keener dethrone Detroit’s longtime leader, WXYZ, and was known for his “Woolyburger” catchphrases and kinetic energy. Ruth saw in Stevens the perfect blend of charisma and control—a jock who could command attention without overshadowing the team.

She made her move. In a bold and strategic recruitment, Ruth lured Stevens away from WKNR and brought him to New York. It was a coup—one of the most talked-about talent shifts in Top 40 history. On April 8, 1965, Gary Stevens debuted on WMCA, stepping into Reed’s former slot and immediately making waves. His arrival was marked by a flurry of promotions, listener buzz, and a palpable sense of excitement.

Stevens didn’t just fill the gap—he redefined it. His rapid-fire delivery, playful banter, and intuitive timing made him a teen idol. He connected with listeners in a way that felt personal, immediate, and thrilling. Ruth gave him room to shine, but within the framework of the Good Guys brand. Stevens became a star, but he remained part of the team—a testament to Ruth’s ability to balance individual talent with collective identity.

The move paid off. WMCA held its own against WABC in the evening hours, and Stevens became one of the most beloved voices in New York radio. Ruth’s decision to recruit him wasn’t just about ratings—it was about vision. She understood that great programming required great people, and that timing, chemistry, and leadership were everything.

Her recruitment of Gary Stevens remains one of the most admired talent moves in radio history—a masterclass in strategic programming, brand stewardship, and emotional intelligence.

Breaking Barriers and Building Brands

By the late 1960s, Ruth Ann Meyer had already proven herself as one of the most innovative programmers in radio history. Her success at WMCA had reshaped the competitive landscape of New York radio, and her “Good Guys” model had become a template for stations nationwide. But Ruth wasn’t content to rest on her laurels. She was a builder, a strategist, and a storyteller—and she was ready to explore new sonic territory.

Her next chapter began at WHN-AM, a station with a modest profile and a bold ambition: to bring country music to New York City. At the time, country was considered a niche genre, largely confined to southern markets and rural audiences. But Ruth saw potential. She understood that country music was rich in storytelling, emotion, and authenticity—qualities that resonated with listeners across demographics.

Under her leadership, WHN pivoted to a full-time country format, becoming New York’s first major country station. Ruth curated the playlist with care, blending Nashville hits with crossover artists like Glen Campbell and Dolly Parton. She coached her DJs to speak with warmth and respect, avoiding caricature and embracing the genre’s depth. The move was risky—but it worked. WHN carved out a loyal audience and proved that country could thrive in the heart of Manhattan.

Ruth’s programming instincts were genre-agnostic. She didn’t chase trends—she anticipated them. After WHN, she took the reins at WNEW-AM, a station known for its adult standards and talk programming. There, she refined the station’s identity, balancing nostalgia with contemporary relevance. Her ability to adapt to different formats was unmatched, and her reputation as a programming architect continued to grow.

In the late 1970s, Ruth was recruited by NBC to lead THE SOURCE, a new rock network aimed at young adults. THE SOURCE was a bold experiment—an attempt to create a national radio brand that could deliver music, news, and lifestyle content to a mobile, college-age audience. Ruth brought her signature blend of structure and soul to the project, shaping its sound and guiding its talent. She understood that young listeners wanted more than music—they wanted connection, and she built a network that spoke their language.

Then, in 1983, Ruth joined ABC Radio Networks to program the ABC Entertainment Network. It was a full-circle moment: from local stations to national platforms, Ruth had become a force in American broadcasting. At ABC, she oversaw a wide range of content, from music specials to syndicated features, always with an ear for quality and a heart for the listener.

Throughout her career, Ruth broke barriers—not just as a woman in a male-dominated field, but as a programmer who believed in emotional resonance. She didn’t just pre-select or schedule playlist songs; she crafted experiences. She didn’t just manage talent; she nurtured voices. Her stations weren’t just successful—they were beloved.

Ruth Meyer’s Reflections: Building the Good Guys, Battling the Odds

From 1958 to 1968, Ruth Ann Meyer was the programming and promotional heartbeat of WMCA 570 AM during its Top 40 heyday. But her vision for the station—centered around unity, branding, and listener connection—didn’t come easy. “Talented air people don’t want to be part of a team,” she recalled in an extensive 2007 Music Radio 77 interview, which was arranged at the time by Scott Benjamin. “They want to be a star.”

Ruth’s solution was radical for its time: she branded the station’s DJs as “The Good Guys”, a collective identity that emphasized camaraderie over ego. She had them wear matching suits, coordinate haircuts, and appear together at remotes. They even recorded a novelty album, “The Good Guys Sing.” Ruth insisted, “Each of them was a star in their time slot, but it’s going to be a group.” She banned on-air sniping and demanded civility, even if personalities clashed behind the scenes.

Ruth’s solution was radical for its time: she branded the station’s DJs as “The Good Guys”, a collective identity that emphasized camaraderie over ego. She had them wear matching suits, coordinate haircuts, and appear together at remotes. They even recorded a novelty album, “The Good Guys Sing.” Ruth insisted, “Each of them was a star in their time slot, but it’s going to be a group.” She banned on-air sniping and demanded civility, even if personalities clashed behind the scenes.

The lineup she curated was legendary: Scott Muni, Harry Harrison, Herb Oscar Anderson, Joe O’Brien, Jack Spector, B. Mitchel Reed, Gary Stevens, and Ed Baer. Each brought a distinct voice, but Ruth’s programming stitched them into a seamless tapestry.

Her branding genius extended to merchandise. Ruth designed the iconic Good Guys sweatshirt herself—a smiley-faced emblem of WMCA’s identity. When management balked at the idea, she quietly commissioned two dozen sweatshirts and had Jack Spector give them away during a remote at Rockefeller Center. The response was overwhelming. Fans mobbed the station, following Spector back to the studios in hopes of scoring one. “We had no money to design them, so I designed them myself,” Ruth said. Today, those sweatshirts remain collector’s items.

Ruth’s radio journey began in the early 1950s after graduating from Kansas City Junior College. Her mother gave her one month to find a job in journalism or settle for secretarial work. She landed at KCKN, writing commercials and assisting programmers, then moved to WHB, where she met Todd Storz, the father of Top 40 radio. “There weren’t any women in radio, but that didn’t seem to bother Todd,” she said.

Her talent soon took her to WMGM in New York, where she worked alongside Peter Tripp. Though she expected to stay only three months, Ruth fell in love with the city—and stayed. At WMCA, she teamed up with General Manager Steve Labunski, a fellow Storz alum. Together, they convinced the Straus family, WMCA’s owners, to adopt the Top 40 format. “They didn’t understand rock music,” Ruth said. But once they did, she had a freer hand than her rival Rick Sklar at WABC, who was hampered by network oversight. “With a family-owned station like WMCA, I could do what I wanted to do.”

WMCA also avoided the payola scandals that rocked competitors like WINS. Ruth made all playlist decisions herself. “Anyone who might offer payola couldn’t get to me,” she said. Her integrity and independence kept the station clean—and credible.

WMCA also avoided the payola scandals that rocked competitors like WINS. Ruth made all playlist decisions herself. “Anyone who might offer payola couldn’t get to me,” she said. Her integrity and independence kept the station clean—and credible.

She had deep admiration for many of her DJs. Scott Muni was “a doll . . . the kindest man,” while Harry Harrison was “enormously talented and the nicest person.” Joe O’Brien was “the bulwark of WMCA . . . calm and never had a harsh word.” Dan Daniel, she said, was “probably the most talented DJ I met in my life,” though “his talent outran his social skills.” Ed Baer was “a sweety-pie . . . you could move him all over the place and he was good at it.”

Others were more challenging. Herb Oscar Anderson “didn’t do anything people told him to do.” Jack Spector was “the strangest man,” often talking about his baseball stats and slamming doors. B. Mitchel Reed, despite living just three blocks from the station, drove in daily and often misplaced his paycheck. Gary Stevens, who succeeded Reed in 1965, was “a talented guy who refused to be part of the team.”

Ruth also praised Music Director Joe Bogart, a former band member and friend of Doris Day, for his uncanny ability to spot hits. She once tried to recruit Dan Ingram, having admired his work in Dallas and St. Louis, but he declined—only to join WABC later and become a legend. “He sent me a sweet note after I had a stroke,” Ruth said.

Her rivalry with Rick Sklar was respectful but wary. “He was always courteous and polite, but suspicious of my motives,” she said. When she proposed a joint emcee event for a Beatles concert, Rick declined. “I didn’t need to trick him to win,” Ruth said. “I wanted to win, but I wanted to do it the right way.”

WMCA’s 5,000-watt signal was no match for WABC’s 50,000 watts, which reached 39 states and beyond. Ruth acknowledged that listeners often switched to WABC during summer vacations and stayed. Yet, in the mid-1960s, WMCA outperformed WABC in New York City itself, thanks in part to its embrace of soul music and its connection to the city’s diverse population.

Ruth Meyer didn’t just program a station—she built a culture. Her blend of discipline, empathy, and innovation made WMCA more than a frequency. It became a feeling, a community, and a legacy.

Beyond the Dial—Legacy, Influence, and the Quiet Power of Ruth Meyer

By the time Ruth Ann Meyer joined ABC Radio Networks in 1983 to program the ABC Entertainment Network, she had already left an indelible mark on American broadcasting. She had built teams, launched formats, mentored talent, and shaped the sound of cities. But Ruth’s influence wasn’t confined to playlists or call letters—it lived in the culture of radio itself.

Ruth Ann Meyer, WHN programmer, photographed during a promotional WHN Country function in the latter-1970s.

She had proven that programming was more than scheduling songs—it was storytelling at scale. Whether she was curating country hits for WHN, crafting rock content for NBC’s THE SOURCE, or overseeing national entertainment features at ABC, Ruth brought the same core values: clarity, cohesion, and connection. She believed that every station, no matter its genre or wattage, had a soul—and it was the programmer’s job to reveal it.

Her leadership style remained consistent across decades. Ruth was known for her quiet confidence, her meticulous attention to detail, and her unwavering belief in the power of team. She didn’t chase trends—she anticipated them. She didn’t micromanage—she mentored. And she never lost sight of the listener. “You have to program for the person in the car, the kitchen, the dorm room,” she once said. “If you’re not speaking to them, you’re just making noise.”

Ruth also opened doors for others. As one of the first women to program major-market stations, she became a role model for generations of female broadcasters. She didn’t trumpet her trailblazing status—she simply did the work, and did it better than almost anyone. Her success was her statement.

Even as the industry evolved—through FM’s rise, syndication’s spread, and digital’s dawn—Ruth’s principles endured. Her emphasis on brand identity, emotional resonance, and talent development became foundational to modern radio strategy. Consultants quoted her. Programmers studied her. DJs remembered her.

And yet, Ruth remained largely behind the scenes. She didn’t seek fame. She didn’t write memoirs or give keynote speeches. Her legacy was in the airwaves—in the laughter of a morning show, the comfort of a familiar jingle, the thrill of a perfectly timed segue. She programmed moments that became memories.

Ruth Meyer’s Professional Honors

• Radio Hall of Fame Inductee

Ruth Ann Meyer is officially honored by the Radio Hall of Fame for her groundbreaking work in programming and promotions. Her induction celebrates her role in shaping the Top 40 format, launching the WMCA Good Guys, and bringing country music to New York City via WHN-AM.

• Peer Recognition and Legacy

While Ruth didn’t seek public accolades during her career, her peers consistently recognized her brilliance. She was widely admired for her strategic talent recruitment, genre versatility, and emotional intelligence in programming. Her influence is cited in forums, online and print tributes, and industry retrospectives as foundational to modern radio culture.

Epilogue: A Life Tuned to Legacy

Ruth Ann Meyer passed away in January 2011, at the age of 80. She died peacefully, listening to Paul McCartney on the radio—a fitting farewell for a woman whose life was scored by the sound of pop, country, and rock. It was as if the music she had championed for decades was gently ushering her home.

Ruth Ann Meyer passed away in January 2011, at the age of 80. She died peacefully, listening to Paul McCartney on the radio—a fitting farewell for a woman whose life was scored by the sound of pop, country, and rock. It was as if the music she had championed for decades was gently ushering her home.

Her passing marked the end of an era—but her influence remains vibrantly alive. Every time a New York station builds a team identity, every time a programmer balances personality with pacing, every time a listener feels seen and heard through the radio, Ruth’s memory was felt. She didn’t just shape formats—she shaped feelings. She understood that radio was more than entertainment; it was companionship, community, and culture.

Ruth never sought the spotlight, but she illuminated the path for others. She was a mentor, a pioneer, and a quiet revolutionary. Her legacy lives on in the voices she nurtured, the brands she built, and the listeners she never met but always considered.

At the USA Radio Museum, we honor Ruth Ann Meyer not just as a programmer, but as a composer of connection. Her work reminds us that behind every great broadcast is a mind that listens, a heart that understands, and a soul that believed in the transformative power of radio through signal and sound.

_________________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_________________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.

The Ruth Meyer story was GREAT!!! I still have my wmca Good Guy sweatshirt and covet it highly. The only disagreement I have is that the 5,000 watt signal was no match for WABC’s 50 kw. Because of it’s low-dial frequency at 570 AM, especially in the daytime, wmca blanketed the NY, NJ & CT area and was, as the story indicated, a fierce competitor. I especially liked learning about what Ruth Meyer did after her success at wmca. Great piece Jim!!!