Introduction: The Detroit Radio Broadcast That Shook the Beatles’ World In the autumn of 1969, Detroit became the unlikely epicenter of one of rock

Introduction: The Detroit Radio Broadcast That Shook the Beatles’ World

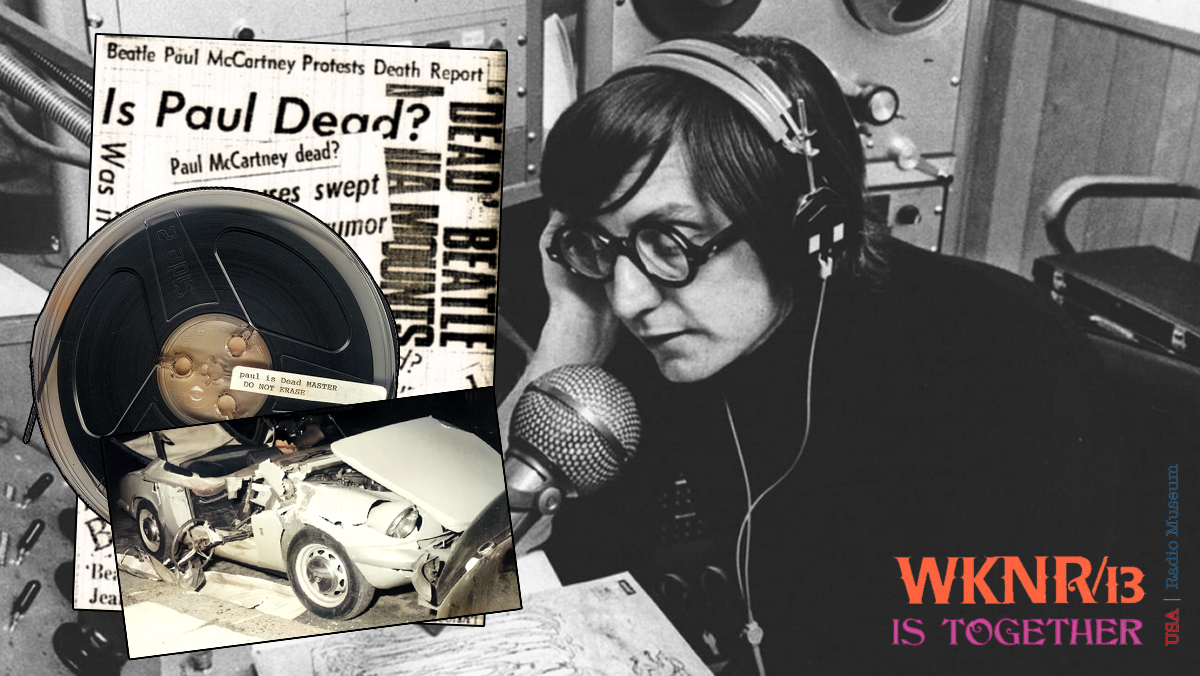

In the autumn of 1969, Detroit became the unlikely epicenter of one of rock history’s strangest and most enduring legends. It began not with a headline, but with a voice—anonymous, insistent, and crackling through the phone lines of WKNR-FM. The claim was simple, chilling, and surreal: Paul McCartney was dead. And the clues were hidden in the music.

What followed was not just a radio broadcast—it was a cultural detonation. WKNR DJ Russ Gibb, already a countercultural icon as the owner of the Grande Ballroom, took the call live on air and leaned into the mystery. He played Beatles records backwards, dissected lyrics, and invited listeners to join the hunt. Within hours, Detroit was buzzing. Within days, the rumor had spread across college campuses, radio stations, and newspapers. Within weeks, it had gone global.

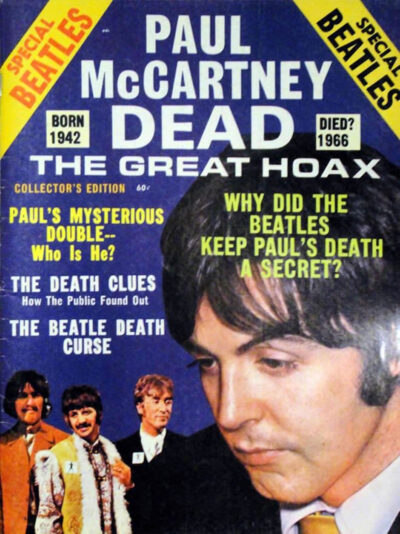

The “Paul Is Dead” phenomenon tapped into the paranoia and playfulness of a generation on edge. In a world reeling from war, assassinations, and the fading glow of the Summer of Love, the idea that one of the Fab Four had died and been replaced by a lookalike felt both absurd and oddly plausible. Fans became detectives. DJs became mythmakers. And radio became the medium through which fiction blurred with fact.

This feature explores the origins of the rumor, the broadcast that ignited it, and the cultural shockwaves that followed. From the reel-to-reel tape that preserved the WKNR moment to the satirical article that turned folklore into frenzy, we trace the story of how Detroit “killed” Paul McCartney—not with malice, but with mystery. Not with silence, but with sound.

Welcome to the USA Radio Museum’s tribute to the night myth met microphone. — USA RADIO MUSEUM

_____________________

Urban Legend: The Night Radio Killed-Off Paul McCartney

The Broadcast That Sparked a Global Rumor

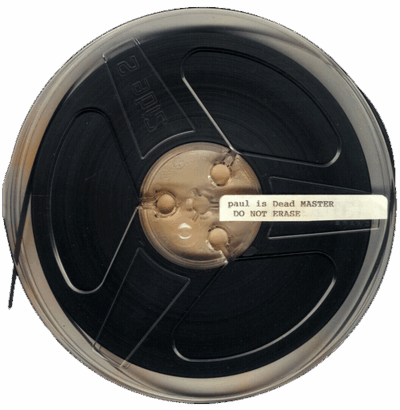

On a Sunday evening in October 1969, WKNR-FM in Detroit aired a program that would become one of the most infamous broadcasts in rock history. Though it was likely simulcast on both WKNR AM and FM, the surviving recording—preserved thanks to a reel-to-reel tape recording (digitized) donated anonymously four years ago to Motor City Radio Flashbacks—appears to have been captured off the AM band, evidenced by the persistent static that threads through the audio. That static, far from diminishing the recording’s impact, only adds to its ghostly allure.

On a Sunday evening in October 1969, WKNR-FM in Detroit aired a program that would become one of the most infamous broadcasts in rock history. Though it was likely simulcast on both WKNR AM and FM, the surviving recording—preserved thanks to a reel-to-reel tape recording (digitized) donated anonymously four years ago to Motor City Radio Flashbacks—appears to have been captured off the AM band, evidenced by the persistent static that threads through the audio. That static, far from diminishing the recording’s impact, only adds to its ghostly allure.

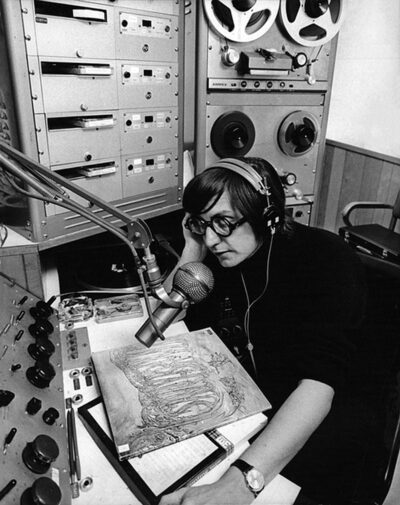

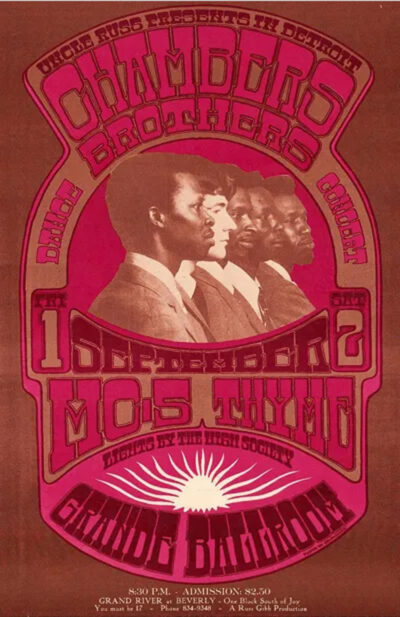

The broadcast featured WKNR personalities John Small, Dan Carlisle, and Russ Gibb, the latter already a local legend as the owner of Detroit’s Grande Ballroom, a psychedelic sanctuary that had hosted the likes of The Who, Cream, and the MC5. But on this night, Gibb wasn’t introducing a band—he was fielding a phone call that would ignite one of the strangest and most enduring conspiracy theories in pop culture.

The caller, whose identity remains unknown, urged Gibb to play The Beatles’ “Revolution 9” backwards. “You’ll hear it,” the voice insisted. “Turn me on, dead man.” Gibb obliged. Whether he truly heard the phrase or simply wanted to believe he did, the moment was electric. The idea that Paul McCartney had died and been replaced by a lookalike wasn’t new—but this broadcast gave it a platform, a voice, and a city of believers.

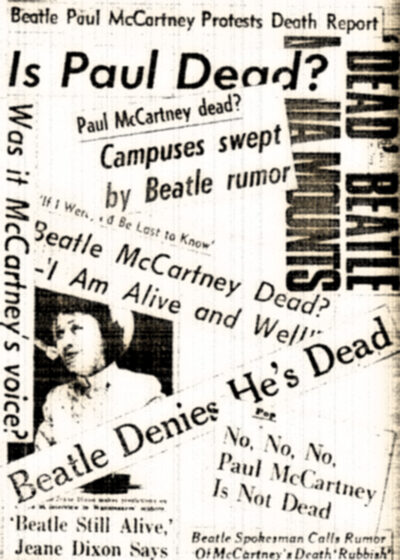

While it’s impossible to confirm whether this was the very first airing of the “Paul Is Dead” theory, it was undeniably one of the earliest and most influential. Within hours, Detroit was buzzing. Within days, the rumor had spread across college campuses, radio stations, and newspapers nationwide. And within weeks, it had gone global.

The Recording’s Journey

The surviving audio of WKNR’s “Paul Is Dead” broadcast owes its existence to one anonymous listener who, in October 1969, had the foresight—or perhaps just the curiosity—to hit a record button. Using a reel-to-reel tape machine, this individual captured the eerie, static-laced transmission as it unfolded live over the airwaves. Whether driven by fascination or happenstance, that act of preservation would prove invaluable decades later.

The surviving audio of WKNR’s “Paul Is Dead” broadcast owes its existence to one anonymous listener who, in October 1969, had the foresight—or perhaps just the curiosity—to hit a record button. Using a reel-to-reel tape machine, this individual captured the eerie, static-laced transmission as it unfolded live over the airwaves. Whether driven by fascination or happenstance, that act of preservation would prove invaluable decades later.

Years passed, and the tape remained in private hands, its origin cloaked in mystery. Eventually, the recording was entrusted to the (former) Motor City Radio Flashbacks archive by the original contributor, who requested complete anonymity and now resides outside the state of Michigan. His donation was not just a gift—it was a resurrection. The reel was carefully converted into a digital format, ensuring that this spectral slice of Detroit radio history could be preserved, studied, and shared.

Today, the digitized file stands as one of the few known surviving artifacts of the original WKNR broadcast. Its crackling fidelity, far from a flaw, serves as a sonic fingerprint of the era—a reminder of the analog intimacy of late-night radio and the moment when myth met microphone.

Fred LaBour and the Michigan Daily Spark

Just two days after Russ Gibb’s electrifying WKNR broadcast, the “Paul Is Dead” theory found its most elaborate—and influential—expansion in the pages of the Michigan Daily. Fred LaBour, a University of Michigan student and aspiring writer, had tuned in to Gibb’s show and was instantly captivated. What he published next wasn’t journalism—it was folklore in the making.

Subtle clues . . . “he blew his mind out in a car . . .”. The alleged Paul McCarthy death car, 1966.

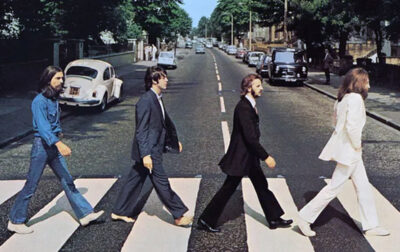

LaBour’s article, written with a satirical edge, laid out a meticulous and imaginative case for McCartney’s alleged death and replacement. He connected dots that had never been meant to align, weaving together visual cues from Beatles album covers, cryptic lyrics, and symbolic gestures into a narrative that felt both eerie and oddly convincing. Among his “evidence” was Paul’s turned back on the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover, the mysterious “OPD” patch on his uniform (interpreted as “Officially Pronounced Dead”), and the barefoot walk across the Abbey Road crosswalk—supposedly a funeral motif.

Though LaBour intended the piece as parody, the tone was straight-faced enough that many readers took it seriously. And in the absence of social media fact-checking or instant rebuttals, the article spread like wildfire. It was picked up by newspapers, debated on college campuses, and dissected in dorm rooms and diners across the country. The Beatles’ music, once a soundtrack to youth and rebellion, had become a cryptic code to be cracked.

Years later, LaBour would admit that much of his article was fabricated—an exercise in creative writing more than investigative reporting. But by then, the myth had taken on a life of its own. The genie was out of the bottle, and Paul McCartney’s supposed demise had become one of the most enduring legends in rock history.

The Beatles Respond (Sort Of)

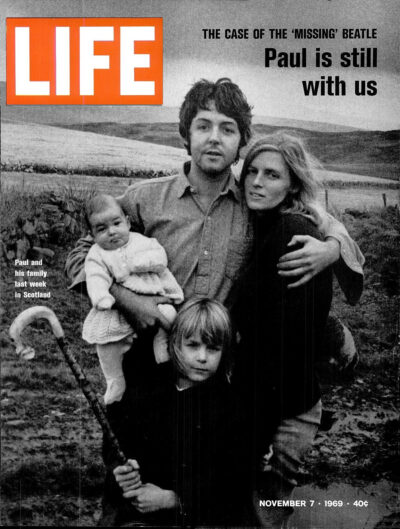

As the “Paul Is Dead” rumor spread like wildfire through radio waves, college campuses, and newspaper columns, the Beatles themselves remained conspicuously silent. Paul McCartney, in particular, had retreated to his farm in the Scottish countryside, far from the public eye. His absence only deepened the mystery. Fans speculated wildly: Was he grieving? Hiding? Or gone altogether?

The silence was deafening. And in that vacuum, the myth grew louder.

The silence was deafening. And in that vacuum, the myth grew louder.

It wasn’t until November 1969 that the world caught a glimpse of McCartney again. A Life magazine photographer tracked him down and captured a candid image of Paul with his wife Linda and their young daughter Mary. In the accompanying interview, McCartney offered a simple rebuttal: “I’m alive and well.” He looked relaxed, bearded, and very much alive—but the photo, rather than quelling the rumor, became part of its lore. Some insisted it was staged. Others claimed it was the lookalike.

The Beatles’ press office eventually issued a formal statement denying the rumor, but by then, the conspiracy had taken on a life of its own. Fans weren’t easily convinced. After all, this was the band that had toyed with symbolism and hidden messages for years. They’d buried clues in album art, layered meanings into lyrics, and played with perception like magicians. Why not now?

The irony was rich: a band that had once thrived on mystery was now trapped by it. Their silence had been interpreted as confirmation. Their denial, as misdirection. And Paul McCartney, very much alive, had become the ghost haunting his own legend.

Echoes Across the Dial: Radio’s National Response to the Death of Paul

Once the WKNR broadcast aired in Detroit in October 1969, the “Paul Is Dead” rumor didn’t just spread—it metastasized. Radio stations from coast to coast began devoting airtime to the mystery, each interpreting the clues through their own lens, each adding fuel to the fire. DJs became detectives, theorists, and provocateurs. The airwaves turned into a nationwide séance.

In New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and beyond, FM and AM stations alike began dissecting Beatles records live on air. “Revolution 9” was played backwards. “Strawberry Fields Forever” was slowed down to isolate John Lennon’s alleged whisper: “I buried Paul.” Album covers were described in vivid detail, with listeners calling in to point out funeral imagery, cryptic gestures, and symbolic clothing. Some stations treated it as satire.

Others leaned into the drama, creating multi-hour specials that blurred the line between journalism and performance art.

College radio stations were especially fervent. Student DJs, inspired by the WKNR broadcast and Fred LaBour’s Michigan Daily article, hosted late-night “Paul Is Dead” marathons. They invited professors of literature and psychology to weigh in on the symbolism. They debated whether the Beatles had orchestrated the hoax themselves as a form of avant-garde commentary. The rumor became a cultural Rorschach test—what you saw in it said as much about you as it did about the music.

Even syndicated programs like The Beatle Years would later devote entire episodes to the phenomenon, treating it as a historical curiosity and a case study in mass media mythmaking. The rumor had become so pervasive that Time, Newsweek, and Rolling Stone all ran features on it, acknowledging that radio had played a central role in turning speculation into sensation.

And then there’s the irony—rich, layered, and uniquely Detroit.

Just five years earlier, in 1964, students at University of Detroit had launched the “Help Stamp Out the Beatles” campaign. It was a tongue-in-cheek protest against Beatlemania, complete with mock rallies and anti-Beatles buttons. Detroit, it seemed, had always had a complicated relationship with the Fab Four. From stamping them out to stamping Paul’s death certificate, the Motor City had a knack for making Beatles history.

In the end, it was radio that gave the rumor its wings. Not newspapers. Not television. Radio—intimate, immediate, and imaginative. DJs didn’t just report the story. They performed it. They invited listeners into the mystery, made them part of the narrative. And in doing so, they proved that the power of radio wasn’t just in transmitting sound—it was in shaping belief.

The Voices Behind the Rumor: Russ Gibb, John Small and Dan Carlisle on WKNR-FM

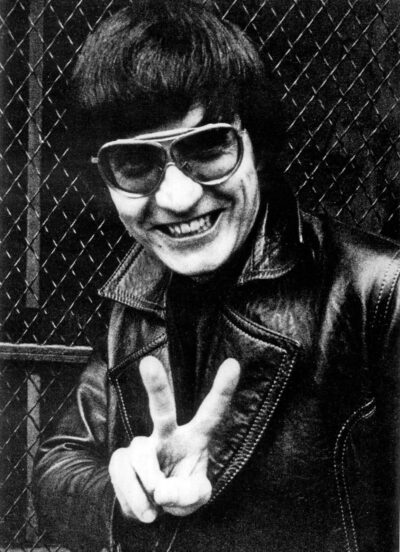

When the “Paul Is Dead” rumor erupted in October 1969, it wasn’t just the theory that captivated listeners—it was the voices that carried it. WKNR-FM in Dearborn, Michigan became ground zero for the broadcast that turned speculation into sensation, and at the heart of it were three free-form radio personalities: Russ Gibb, John Small, and Dan Carlisle.

Russ Gibb, already a legend in Detroit’s music scene as the owner of the Grande Ballroom, brought a theatrical flair and countercultural edge to the airwaves. His free-form radio show was a sonic playground—wild, unpredictable, and deeply attuned to the underground. When the now-famous call came in suggesting Paul McCartney had died and been replaced, Gibb didn’t dismiss it. He leaned in, dissecting Beatles tracks live on air, inviting listeners to decode clues, and turning WKNR into a cultural amplifier.

John Small, his on-air partner that night, played a quieter but equally vital role. Together, they created a broadcast that felt more like a séance than a show—probing lyrics, playing records backwards, and letting the audience shape the narrative in real time. Their chemistry gave the moment its momentum. It wasn’t just what they said—it was how they said it: curious, conspiratorial, and compelling.

Dan Carlisle, another WKNR-FM free-form voice, added his own distinctive tone to the mix. Known for his deep musical knowledge and laid-back delivery, Carlisle helped shape the special broadcast titled “The Beatle Plot,” which aired on October 19, 1969. His presence added texture and credibility to the unfolding mystery, anchoring the broadcast with a sense of wonder and wit. Carlisle’s voice, alongside Gibb and Small, helped transform the rumor into a full-blown cultural event.

The program was so impactful that it was simulcast on both WKNR-FM and WKNR-AM, amplifying its reach across Detroit and beyond. The unmistakable station ID voice of Paul Cannon, typically heard on the AM side, confirmed the dual-channel broadcast—ensuring that the rumor echoed across every frequency.

Russ Gibb’s legacy extended far beyond that night. He spent decades as a beloved teacher in the Dearborn Public Schools, where he taught video production and mentored generations of students. He retired in 2004 after 42 years in education. Gibb passed away on April 30, 2019, at the age of 87. His impact—as a DJ, promoter, educator, and provocateur—is still felt in Detroit and far beyond.

As for John Small and Dan Carlisle, their voices remain preserved in the original reel-to-reel recording of “The Beatle Plot.” While current details about their lives and status are limited to this author, at the present, their contributions to that surreal night remain etched in Detroit radio folklore and history.

Together, Gibb, Small, and Carlisle didn’t just report a rumor. They gave it rhythm, resonance, and reach.

_____________________

WKNR-AM | The Beatle Plot | October 19, 1969

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

The Lennon Call: WKNR-FM Confronts the Rumor

Just days after WKNR-FM’s “The Beatle Plot” broadcast ignited national fascination with the “Paul Is Dead” theory, Detroit radio struck again—this time with a voice from the source. On October 22, 1969, WKNR’s John Small conducted a live telephone interview with John Lennon, confronting the swirling rumors head-on.

Lennon’s tone was clear and candid. “Paul is very much alive,” he said, brushing off the conspiracy as “a joke.” He added pointedly, “If Paul was dead, we would have been the first to know . . . we would have told you so.” Even Yoko Ono, present during the call, chimed in to dismiss the hysteria. Their voices brought a dose of reality to a story that had spiraled into surrealism.

When Small pressed Lennon about the so-called “clues” fans had unearthed—cryptic lyrics, symbolic album covers, reversed audio—Lennon responded with bemused disbelief. “I knew nothing about any of this until I read about it in the newspapers,” he said, underscoring how detached the Beatles themselves were from the rumor’s elaborate mythology.

This aircheck is a cultural artifact: a moment when radio didn’t just spread a legend—it challenged it. The fact that WKNR-FM secured Lennon’s voice so swiftly after the rumor broke speaks to the station’s influence and urgency. It also reveals how deeply the “Paul Is Dead” story had penetrated public consciousness—enough to warrant a Beatle’s direct response.

For the USA Radio Museum, this recording is more than a rebuttal. It’s a reminder of radio’s power to connect, clarify, and confront. And it belongs in the heart of the exhibit—not just as a counterpoint, but as a testament to how truth and myth danced across the dial in October, 1969.

_____________________

WKNR-FM | Is Paul McCartney Dead? | John Small Interviews John Lennon and Yoko | October 22, 1969

Audio Digitally Remastered by USA Radio Museum

_____________________

The Grande Ballroom Connection

To understand Russ Gibb’s role in the “Paul Is Dead” phenomenon, one must first understand the cultural gravity of the Grande Ballroom. In the late 1960s, it wasn’t just a venue—it was Detroit’s psychedelic cathedral. Under Gibb’s stewardship, the Grande became a sanctuary for sonic revolution, hosting the likes of Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin, Pink Floyd, and the MC5. It was a place where music wasn’t just heard—it was experienced, felt, and transformed into something transcendent.

Gibb himself was more than a promoter. He was a provocateur, a tastemaker, and a conduit between the underground and the mainstream. His radio show on WKNR-FM mirrored the spirit of the Grande: wild, experimental, and deeply plugged into the counterculture. He didn’t just play records—he curated moods, challenged norms, and invited listeners into a shared hallucination of sound and possibility.

So when the call came in on that October night—when a listener claimed Paul McCartney was dead and that clues were hidden in Beatles songs—Gibb didn’t scoff or shut it down. He leaned in. He played the records backwards. He dissected lyrics. He opened the phone lines. He let the audience decide what was real and what was myth. That openness, that willingness to entertain the absurd without judgment, is what made the broadcast so powerful.

Gibb didn’t manufacture the rumor, but he gave it oxygen. He understood that radio wasn’t just a medium—it was a mirror, a magnifier, and sometimes, a myth maker. In that moment, he wasn’t just a DJ. He was the ringmaster of a cultural séance, inviting listeners to decode, to believe, and to wonder.

Legacy and Resonance

More than half a century later, “Paul Is Dead” remains one of rock’s strangest and most enduring myths—a hoax, yes, but also a cultural mirror held up to a generation hungry for mystery, meaning, and connection. In the absence of social media, before the age of viral videos and algorithmic amplification, it was radio that carried the rumor. It was the DJ and the dial that shaped public imagination. And it was Detroit, through the voice of Russ Gibb, that gave the myth its first breath.

The USA Radio Museum honors that legacy not as a curiosity, but as a testament to the power of broadcast storytelling. We preserve the tapes, the voices, the static-laced transmissions that once turned speculation into sensation. We remember Russ Gibb not as the “ghoul who killed Paul,” but as a provocateur, a cultural conjurer, and a man who understood that sometimes the most powerful truths are wrapped in fiction. He didn’t just report a rumor—he orchestrated a moment. He invited listeners to wonder, to question, to decode.

And we remember that night in Detroit—not as a prank, but as a phenomenon. Not as a death, but as a resurrection of imagination. Paul McCartney was never gone, but for a brief, surreal moment, the world believed he might be. And in that belief, radio proved its magic.

It wasn’t silence that stirred the myth. It was sound.

The Rumor That Refuses to Die: How New Generations Keep Paul’s “Death” Alive

Though the “Paul Is Dead” phenomenon first exploded in 1969, its roots reach back to the alleged car crash of 1966—and its branches stretch far into the present. What began as a surreal radio broadcast and a college newspaper prank has become one of the most enduring urban legends in pop culture history. And remarkably, it’s not just boomers who keep the mystery alive. It’s Gen Z. It’s digital sleuths. It’s YouTube creators, TikTok theorists, and Reddit detectives who weren’t even born when the Beatles broke up.

Today, the legend flourishes in a new medium: the internet. YouTube is filled with documentaries, breakdowns, and backward audio analyses. TikTok users post side-by-side comparisons of Paul’s face “before and after 1966.” Podcasts dissect the clues with fresh eyes, blending folklore, psychology, and pop culture critique. The myth has become a digital campfire—where each generation gathers to retell, reframe, and reimagine the story.

Today, the legend flourishes in a new medium: the internet. YouTube is filled with documentaries, breakdowns, and backward audio analyses. TikTok users post side-by-side comparisons of Paul’s face “before and after 1966.” Podcasts dissect the clues with fresh eyes, blending folklore, psychology, and pop culture critique. The myth has become a digital campfire—where each generation gathers to retell, reframe, and reimagine the story.

What’s striking is how the rumor has evolved. It’s no longer just about whether Paul died. It’s about symbolism, media manipulation, and the power of collective belief. For younger fans, it’s a gateway into Beatles history—a mystery that invites them to listen closely, look deeply, and question everything. The clues are still there: the barefoot walk on Abbey Road, the cryptic lyrics, the reversed tracks. But now, they’re decoded with new tools, new voices, and new urgency.

In this way, “Paul Is Dead” has transcended its origins. It’s no longer just a conspiracy theory. It’s a cultural ritual. A myth that renews itself with every retelling. And at its heart is radio—the medium that first gave it breath. From WKNR’s reel-to-reel to today’s streaming platforms, the rumor lives on in sound.

At the USA Radio Museum, we honor this story not because it’s true, but because of its lasting endurance. For it reminds us that legends don’t die. They adapt. They re-echo. And sometimes, they begin as a speculative rumor, carried by a voice on the dial—never quite fading, even as the decades stretch on and new generations lean in to listen, and, that alone, we find that quite amazing to behold.

Conclusion: The Broadcast That Never Died

The “Paul Is Dead” phenomenon may have begun with a single phone call to WKNR, but its echo traveled far beyond Detroit. It became a moment when radio didn’t just report culture—it created it. DJs across the country transformed their studios into detective dens, their playlists into puzzles, and their microphones into myth-making machines. The rumor wasn’t just heard—it was believed, debated, and immortalized.

The “Paul Is Dead” phenomenon may have begun with a single phone call to WKNR, but its echo traveled far beyond Detroit. It became a moment when radio didn’t just report culture—it created it. DJs across the country transformed their studios into detective dens, their playlists into puzzles, and their microphones into myth-making machines. The rumor wasn’t just heard—it was believed, debated, and immortalized.

And in doing so, radio proved that its power wasn’t merely in transmitting sound—but in the Paul Is Dead case, it was in shaping and spreading rumored belief as no other time in radio history. It was a moment when static became sacred, when speculation became sensation, and when the voice of a DJ could ripple across continents.

Detroit’s role was no accident. This was the same city where, in 1964, students at the University of Detroit launched the “Help Stamp Out the Beatles” campaign—a satirical protest against Beatlemania. Five years later, Detroit wasn’t stamping out the Beatles. It was stamping Paul McCartney’s death certificate. The irony is rich. The impact, undeniable.

At the USA Radio Museum, we preserve this story not to prove or disprove it, but to honor the moment when radio reached its most surreal crescendo. We remember Russ Gibb not as the man who killed Paul, but as the man who dared to ask, “What if?” We remember the listeners who leaned in, the students who theorized, the DJs who played the clues. And we remember the sound—not just of Beatles records, but of belief being born in real time.

The broadcast may have ended. But the mystery, well? . . . . that never really quite did.

_____________________

Contact: jimf.usaradiomuseum@gmail.com

_____________________

A USARM Viewing Tip: On your PC? Mouse/click over each image for expanded views. On your mobile or tablet device? Finger-tap all the above images inside the post and stretch image across your device’s screen for LARGEST digitized view. Then click your brower’s back arrow to return to the featured post.

© 2025 USA Radio Museum. All rights reserved.

Fantastic resources all in one place! Remember this like it was yesterday. This could be the precursor of conspiracy theories pre-internet. Shows the impact and communication dominance of broadcast radio at that time. Thank you for sharing.